Table of Contents

Unlike most southern universities, the University of Virginia remained open throughout the Civil War. However, the opening of the Charlottesville General Hospital on the grounds of the University significantly altered the lives of students, professors, and residents, both enslaved and free.

Student enrollment plummeted at the outbreak of the Civil War, as hundreds of young men paused their studies to enlist in the Confederate army. In 1860, the University boasted 604 students. By fall 1861, the number dropped to 66. In 1862, student enrollment fell to 46 and never climbed above 60 during the war.[1] As students departed or elected not to enroll, the Confederate hospital moved in.

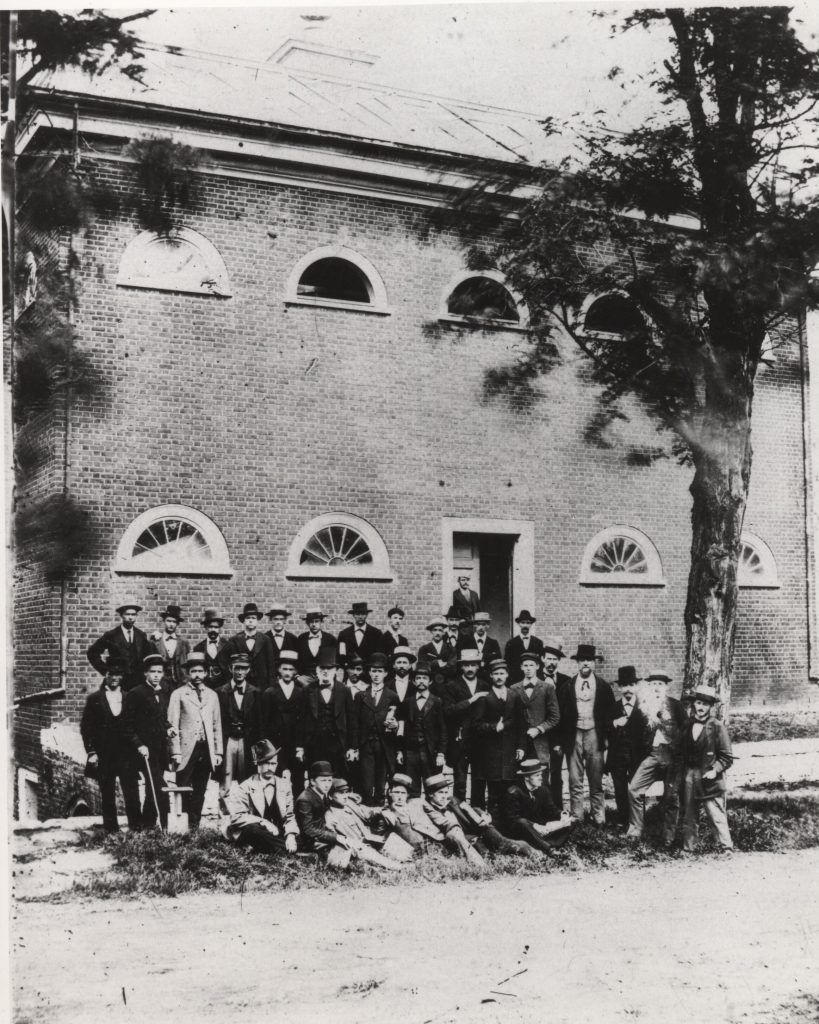

Before the outbreak of the Civil War, the University of Virginia School of Medicine counted among the premier medical schools in the country. Founder Thomas Jefferson recommended the University include a School of Anatomy and Medicine, which opened in 1825 as the tenth medical school in the country.[2] Charlottesville lacked a teaching hospital, however, which made the medical curriculum primarily theoretical.[3] Courses included materia medica, anatomy, and physiology.[4] To provide students a setting to gain practical knowledge, the University erected an anatomical theater in 1825-27 based on Thomas Jefferson’s architectural sketches. Regarding the anatomical theater, Jefferson believed, “There cannot be a single dissection until a proper theatre is prepared giving an advantageous view of the operation to those within, and effectually excluding observation from without.”[5] The establishment of the Charlottesville General Hospital represented the first instance that medical students at Virginia could regularly implement what they learned in the classroom.

The Confederate government selected Charlottesville as the site of a general hospital for several reasons. According to historian T.A. Wheat, “Because most of coastal Virginia quickly fell under Union control, transportation of Confederate casualties was primarily by rail. Cities and towns along these rail lines became hospital centers.”[6] Conveniently, both the Virginia Central and the Orange and Alexandria railway lines passed through Charlottesville. Furthermore, Charlottesville’s proximity to Richmond made it a highly attractive candidate for a military hospital.[7] The Confederate government planned to draw upon the faculty and students of the medical school in addition to the local enslaved population to staff and support the proposed hospital. The Town Council of Charlottesville provided partial funding for the hospital.[8]

The Charlottesville General Hospital took over various building across the University of Virginia’s grounds. Places that had once housed students began to hold patients.[9] The hospital leadership briefly considered using Monticello as a smallpox outpost, although the plan never came to fruition. Ultimately, the Charlottesville General Hospital remained concentrated around the Academical Village of the University. Eventually, the hospital opened in July 1861 and “grew to a capacity of 500 beds staffed by between fifteen and fifty doctors.”[10] The first casualties to arrive at the hospital came from the Battle of Manassas in July 1861.[11]

The Charlottesville General Hospital leadership included both Confederate army officers and University of Virginia medical faculty. The Surgeon General in Richmond oversaw the operation of the hospital in Charlottesville. Faculty member Dr. James Lawrence Cabell served as the Chief Surgeon. The owner of three slaves, Cabell ardently supported the Confederacy, and his wife hosted the Ladies Relief Society of Albemarle County in their home. Drs. John Staige Davis and J. Edgar Chancellor supported Cabell in running the bustling hospital. The medical staff included Dr. Orianna Moon, the sole female doctor at the Charlottesville General Hospital.[12]

Moon served as the superintendent of the hospital’s nurses. She had graduated from the Female Medical College of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1857. At the time, she counted among only 38 women in the United States to hold medical degrees.[13] The medical inspector of the Army of Northern Virginia, Dr. Edward Warren observed Moon working in the hospital. He described her as “‘a lady of high character and of fine intelligence’” but patronizingly believed “women should not ‘dream of entering the ranks of the medical profession.’”[14] Moon married a fellow doctor at the general hospital named Dr. John Summerfield Andrews. Shortly after their wedding, the couple relocated to Richmond in November 1861.[15] Finding the barriers to practicing medicine as a woman incredibly high, Moon eventually ceased her career in favor of homemaking.[16]

The opening of the hospital affected almost every aspect of student life for the few men who remained at the University. Initially, the University ardently cooperated with the Charlottesville General Hospital and the Confederate government. However, as the hospital’s impact grew increasingly severe, tensions rose between the Surgeon General’s office and University officials. The faculty wanted to regain access to academic buildings, which the hospital had increasingly encroached upon. Several students even withdrew from their studies to volunteer at the hospital.[17] To offset the cost of damages that hospital operations caused to the buildings, the Board of Visitors (the University’s board of governors) resolved on July 4, 1863 to petition the Confederate Secretary of War to send prisoners sentenced to hard labor to work on the University.[18]

The general hospital heavily impacted Charlottesville African American residents, both enslaved and free. Many slave owners forced their enslaved workers to labor at the hospital. Additionally, Cabell and other hospital doctors conducted physical examinations of conscripted black men before subjecting them to various manual labor tasks on behalf of the Confederacy.[19] Seeking employment to sustain their families, many free black women worked at the hospital as nurses. They received a pay of $18.50 a month in October 1861, which then increased to $20 in 1862.[20]

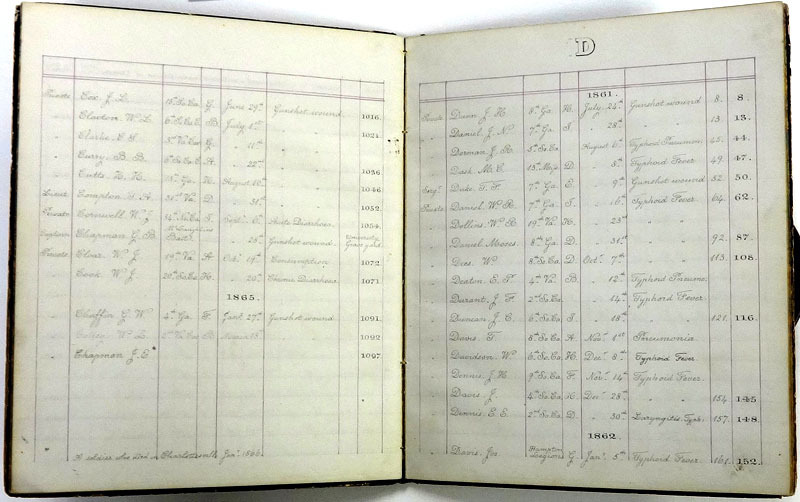

The Charlottesville General Hospital served an extraordinary number of patients despite numerous setbacks. The medical faculty, nurses, student volunteers, and enslaved laborers at the hospital treated approximately 22,700 men between 1861-1865. Of those patients, 5,000 received treatment for gunshot wounds.[21] The Federal blockade resulted in perpetually inadequate medical supplies at the hospital.[22] Huge influxes of casualties also strained hospital resources. After the Battle of Port Republic in June 1862, a record 1,400 patients arrived at the hospital.[23] As a result, the hospital commandeered additional academic buildings, infuriating the Board of Visitors, who condemned the act as unauthorized. Although the Board of Visitors and faculty repeatedly protested, Confederate forces continued to occupy University space. [24]

Hospital records indicate over 1,100 patients died at Charlottesville General Hospital. The task of grave digging usually fell to the conscripted black laborers, who buried the Confederate dead in a plot adjacent to the University cemetery on current-day Alderman Road. A total of 1,097 soldiers were interred in the cemetery during the war.[25] The plot also held 10 Union prisoners of war who had died at the hospital, likely from wounds incurred during battle. The federal government reinterred the Union veteran’s bodies in the national cemetery in Culpepper, Virginia.[26]

On March 3, 1865, Union forces retook Charlottesville. Following the town’s surrender to Phillip H. Sheridan’s forces, the Charlottesville General Hospital continued to treat both Union and Confederate patients until the conclusion of the war. Despite the University’s initial enthusiasm in 1861, the Charlottesville General Hospital and the University of Virginia sustained a tenuous relationship throughout much of the Civil War. Ultimately, the ardent Confederate patriotism of most professors, administrators, and students partially offset their frustrations with the chaotic realities of hosting a military hospital.

Learn more in this interview with Amelia Wald, the post’s author

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Amelia F. Wald graduated with High Distinction from the University of Virginia in May 2019. She studied in the Distinguished Majors Program in History, where she wrote her thesis on courts martial in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. While at UVA, she was a Sewell Undergraduate Research Fellow at the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History. She is currently the Executive Director of the Virginia Club of New York in New York City.

Endnotes

[1] Philip Alexander Bruce, History of the University of Virginia: 1819-1919, (New York: MacMillan, 1921), 3:321.

[2] “Medicine at UVA — A Brief History.” University of Virginia School of Medicine. Accessed September 8, 2019. https://med.virginia.edu/internal-medicine-residency/why-uva/about-uva/history/.

[3] UVA Health System: 200 Years of Learning, Research, & Care. Edited by Holly Robertson. Charlottesville: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, 2018. Exhibition.; Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., Charlottesville and the University of Virginia in the Civil War, 2nd ed. (Lynchburg, VA: H.E. Howard, 1988), 32, 47-58.

[4] Bruce, 322.

[5] Janet Pearson, M.C. Wilhelm, et al. “Anatomical Theater at the University of Virginia.” Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. Accessed September 8, 2019. http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/anatomical-theatre.

[6] T.A. Wheat, “Medicine in Virginia during the Civil War.” Encyclopedia Virginia. April 27, 2016. Accessed September 8, 2019. https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Medicine_in_Virginia_During_the_Civil_War#start_entry.

[7] Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., “Charlottesville during the Civil War.” Encyclopedia Virginia. November 19, 2015. Accessed September 8, 2019. https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Charlottesville_During_the_Civil_War.

[8] Jordan, Charlottesville and the University of Virginia in the Civil War, 49.

[9] Ibid, 50.

[10] Jordan, “Charlottesville during the Civil War.”

[11] Jordan, “The University of Virginia during the Civil War.”

[12] Jordan, Charlottesville and the UVA in the Civil War, 35, 47-58, 82.

[13] Jordan, “Charlottesville during the Civil War.”

[14] Jennifer Davis McDaid, “Oriana Russell Moon Andrews (1834–1883),” Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia, 2016. Accessed September 8, 2019. http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Andrews_Oriana_Russell_Moon.

[15] Jordan, “Charlottesville during the Civil War.”

[16] McDaid, “Oriana Russell Moon Andrews (1834–1883).”

[17] Jordan, Charlottesville and the UVA in the Civil War, 49.

[18] University of Virginia, Public Minutes of the Board of Visitors, entry for July 4, 1863, Jefferson’s University: Early Life (hereafter JUEL). Accessed September 8, 2019. http://juel.iath.virginia.edu/node/343?doc=/juel_display/BOV/1860/bov_18630702

[19] Jordan, Charlottesville and the UVA in the Civil War, 40.

[20] Ibid, 55.

[21] Ibid, 58.

[22] Ibid, 51.

[23] Ibid, 50.

[24] Ibid, 49.

[25] Jordan, “Charlottesville during the Civil War.”; Who shall tell the story?”: Voices of Civil War Virginia. Curated by Gayle Cooper, et al. Charlottesville: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, 2014. Exhibition. https://explore.lib.virginia.edu/exhibits/show/voicesofcivilwarvirginia/1863/painandpantingofdeath.

[26] Ibid, 35-37, 58.; Gayle M. Schulman, “The Gibbons Family: Freedmen,” The Magazine of Albemarle County History 55 (Charlottesville: Albemarle County Historical Society, 1997), 92.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.