Table of Contents

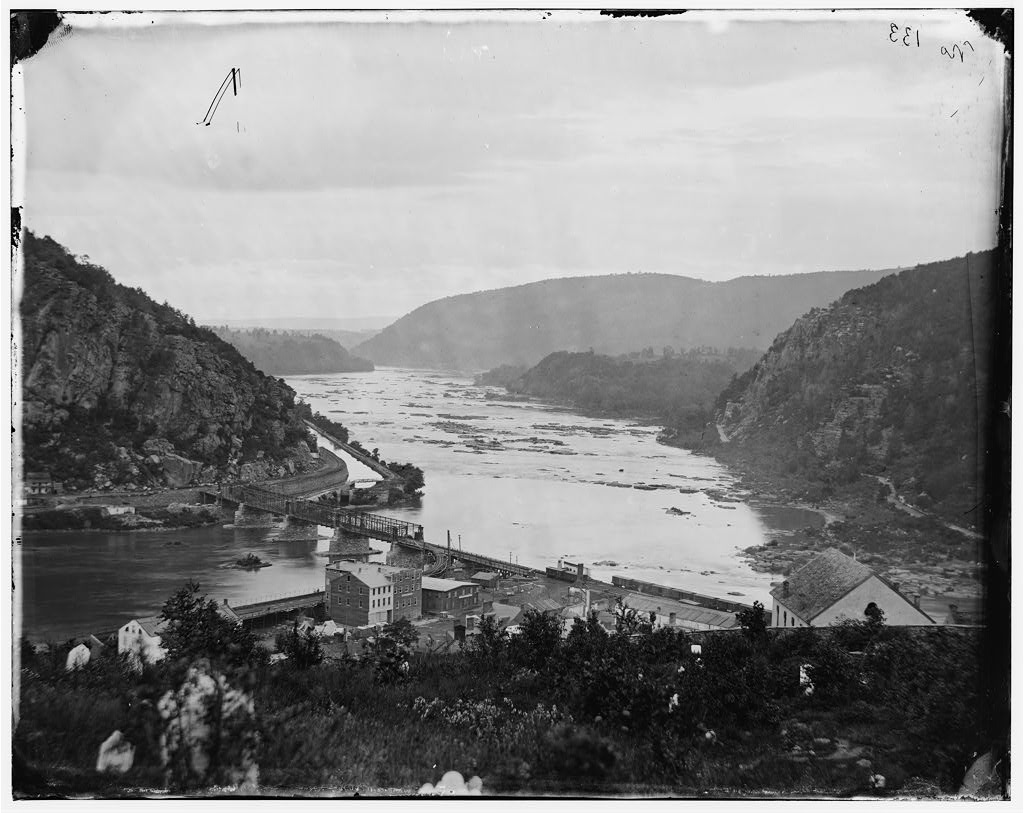

Harpers Ferry is a tranquil place. Thomas Jefferson described the view of the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers as “worth a voyage across the Atlantic” (although John Quincy Adams later said “those who first see it after reading Mr. Jefferson’s description are usually disappointed”). Amid the tumult of the Civil War, the natural beauty and central location made Harpers Ferry an ideal location for a long-term military medical facility. However, Harpers Ferry proved time and time again to be a dangerous place. For both hospital patients and the soldiers assigned to the area.

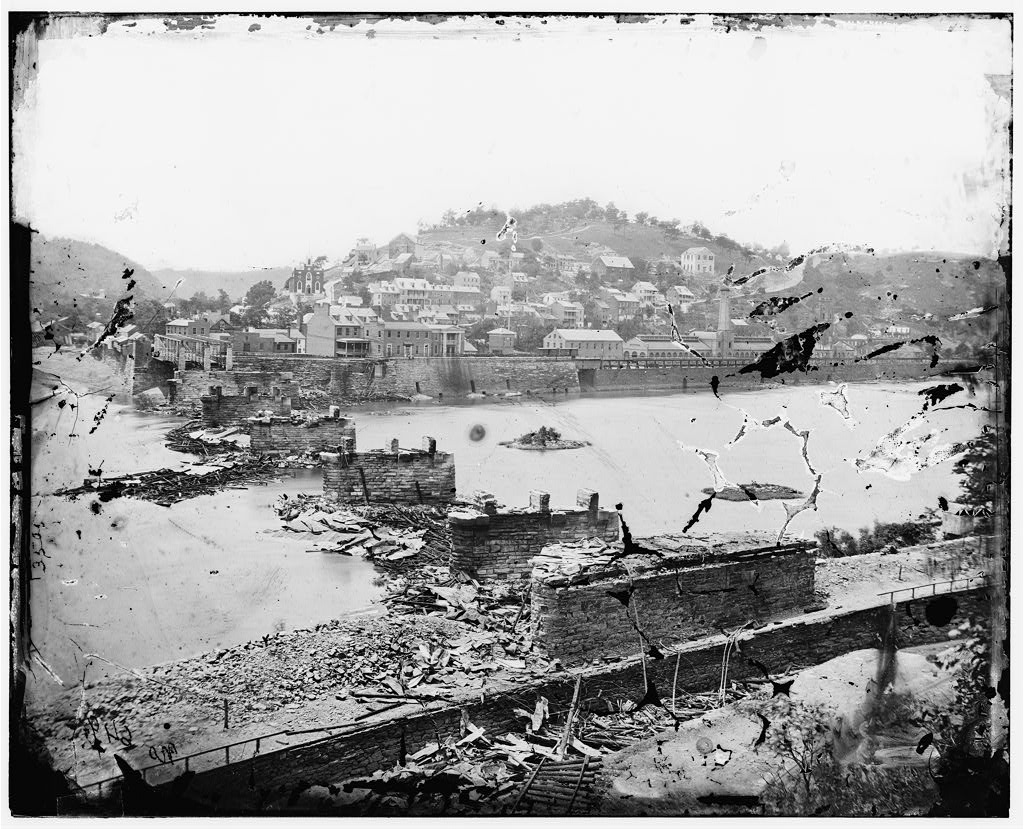

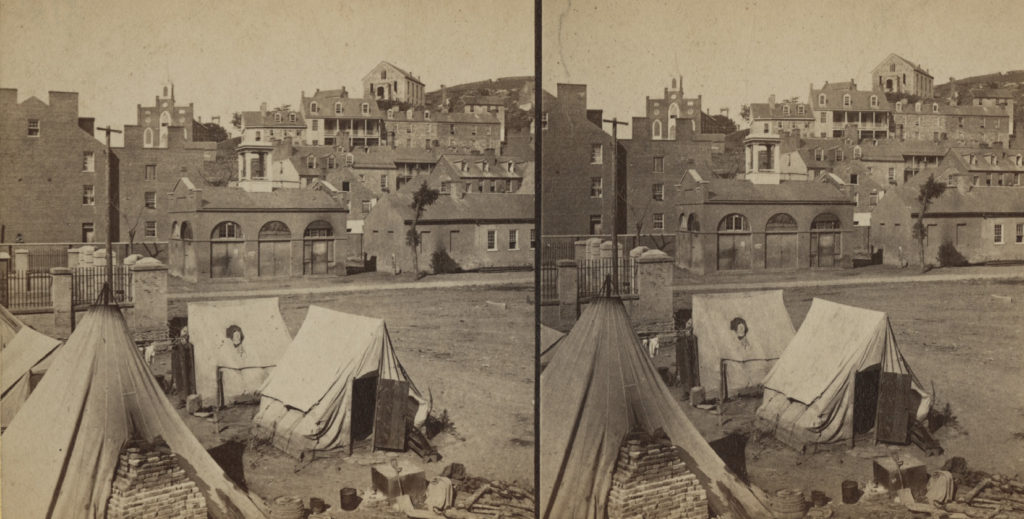

Rising above the lower portion of Harpers Ferry adjacent to the rivers is a large knoll, known as Camp Hill, which comprised the upper town where many of the town’s wealthy residents lived. With the destruction of the US Armory by Confederate soldiers at the outset of the war, most Armory officials left the town and their mansions behind. The vacant two-story former Armory Paymaster’s House was ultimately chosen as a hospital site in the summer of 1862 – sometimes going by the name of Clayton General Hospital. The house and grounds could accommodate a maximum of 370 patients at a time when tents were set up on its expansive lawn.

Initially, the hospital housed sick patients primarily from the Union garrison assigned to guard the nearby portions of the B&O Railroad (an important Federal supply line) from Confederate raiders. They also housed wounded soldiers from the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of spring 1862. The medical staff stayed in an adjacent building (which used to belong to the Armory Superintendent’s Clerk) and were drawn from surgeons assigned to regiments stationed at Harpers Ferry. With the medical staff rotating frequently, the only constants were local townspeople who volunteered their time and resources caring for soldiers there. Volunteer nurse Abba Goddard who followed her hometown unit, the 10th Maine, to the front to care for them was another constant.

In the early days of Clayton General Hospital, a New York Times correspondent wrote favorably about the conditions there, stating that Harpers Ferry “is certainly one of the healthiest points in the United States, having been much resorted to by invalids prior to this rebellion. The harsh, severe weather of Northern latitudes is not experienced here; nor, on the other hand, the oppressive heats of more Southern localities. The climate presents that happy medium so conducive to health and enjoyment.” Beyond that, the patients reportedly found it “exhilarating” to be wheeled onto the second story balcony to look out at the view that Thomas Jefferson described so eloquently.[1]

As the summer wore on, more and more patients who were wounded in April, May, and June began to return to their units or head home in July and August. By the beginning of September, the hospital was almost empty. But the calm soon ended. Those first weeks of September brought word that a sizable Confederate force was moving toward Harpers Ferry.

On September 13, 1862, 28,000 Confederate soldiers under the command of the famed “Stonewall” Jackson arrived in the vicinity of the town. Their mission: capture the 14,000-man US Army garrison that threatened to disrupt Confederate supply lines during the 1862 Maryland Campaign.

The Confederate arrival prompted sudden “ailments” among some soldiers on the front lines. Nurse Abba Goddard recorded that “our empty hospital quarters were turned into barracks and occupied by some three hundred scared, weak-backed cowardly sneaks, who became suddenly afflicted with crickintheback, paininthestomach, weakness in the knees, etc – contracted in anticipation of a visit from Stonewall Jackson.”[2]

Soldiers weren’t the only ones who felt fear as Confederate forces approached. Harpers Ferry resident Mary Clemmer Ames witnessed a group of formerly enslaved African Americans who had sought refuge behind Federal lines, known as contrabands, “talking in incoherent terror” of what might happen to them if Confederate soldiers occupied the town. Soldiers stationed at Harpers Ferry estimated there were as many as 5,000 contrabands living in and around town in September 1862. If Jackson’s troops captured the garrison, it seemed likely that all the contrabands would be sent South and returned to bondage.[3]

When Confederate soldiers appeared on September 13, they surrounded Harpers Ferry – taking the highest point from Federal soldiers, Maryland Heights, after a short but sharp fight which sent dozens of wounded to the hospital on Camp Hill. The trapped Union garrison and townspeople spent the next day in nervous anticipation hoping for reinforcements.

Mary Clemmer Ames wrote on September 14 about the dread in waiting for “the terrors of the day.” While sitting in the window of her home near Clayton General Hospital making bandages she saw “young girls and matrons pass[ing] up the hospital path laden with baskets of delicacies, mindful of the suffering soldiers amid all their fears.”[4]

Around 2:00 PM on the 14th, the tension broke. For five hours, 50 Confederate cannons bombarded Union positions and, though it wasn’t the target, portions of Harpers Ferry.

“The windows rattled, the house shook to its foundations. Heaven and earth seemed collapsing,” Mary Ames remembered. After the bombardment, Abba Goddard reported that “some of our hospital tents were riddled with shell, but fortunately not one exploded, and consequently nobody was hurt.”[5]

The Federal soldiers refused to surrender the area in spite of the heavy cannonading. That evening, General Jackson executed a dramatic flanking maneuver, placing a number of his troops on the Union left flank and prepared for an assault in the morning. When the fog lifted on the morning of September 15, it became clear to Colonel Dixon Miles, the Union commander, that their position was indefensible. He surrendered the Harpers Ferry garrison in its entirety. Harpers Ferry marked the largest surrender of United States troops to that point (12,500) only to be eclipsed during World War II at the Battle of Bataan in 1942.

Not only did the Rebels gain 12,500 prisoners, they also spent the next three and a half days capturing the ample supplies located in town. Nurse Goddard recounted, “The rebels carried away hardbread, rice, coffee, sugar, molasses, pork, beef, and beans…” In total the Confederates made off with 156,000 pounds of hardtack, 19,000 pounds of bacon, 1,500 pounds of salt beef, 1,300 pounds of salt pork, and 4,900 pounds of coffee (not to mention thousands of wagons, horses, and ammunition).[6]

Confederate soldiers also carried off large numbers of black refugees in Harpers Ferry. Nurse Goddard described the scene in town following the surrender.

It is well known that the slaves follow in the wake of our army; an immense number of these poor God-forsaken creatures had sought protection in the Ferry…But with the influx of rebel troops came the human hyenas in search of living prey. Every nook, corner, cranny, barn, and stye has been searched, and men, women, and little children in droves, have been carried off.[7]

Goddard did what good she could, though. By hiding seven black hospital cooks and laundresses in the basement of the hospital, she prevented their capture. After several days of Confederate occupation, she related that “I am almost tired of night-watching, and my revolver begins to grow heavy.”[8]

Union soldiers reentered the town on September 19, just two days after the nearby Battle of Antietam and one day after the last Confederates left. They encountered hundreds of unburied bodies atop Maryland Heights, burned-out supply buildings, and Nurse Abba Goddard caring for 300 sick and wounded soldiers. She “screamed [herself] hoarse with gladness” at the sight of friendly troops. The nightmare was finally over. [9]

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Endnotes

[1] New York Times, August 21, 1862.

[2] Portland Daily Press, October 1, 1862.

[3] Dennis E. Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire: A Border Town in the American Civil War (The Donning Company Publishers, 2012), 75-76, 88.

[4] Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire, 73, 87-88.

[5] Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire, 88-89.

[6] Portland Daily Press, October 1, 1862; Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire, 102.

[7] Portland Daily Press, October 1, 1862.

[8] Portland Daily Press, October 1, 1862.

[9] Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire, 106-109.

About the Author

John Lustrea is a member of the Education Department and the Website Manager at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He earned his Master’s degree in Public History from the University of South Carolina. Lustrea previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park during the summers of 2013-2016.