Table of Contents

Museum members are the reason we can bring you scholarship like this.

CONSIDER SUPPORTING THE MUSEUM TODAY

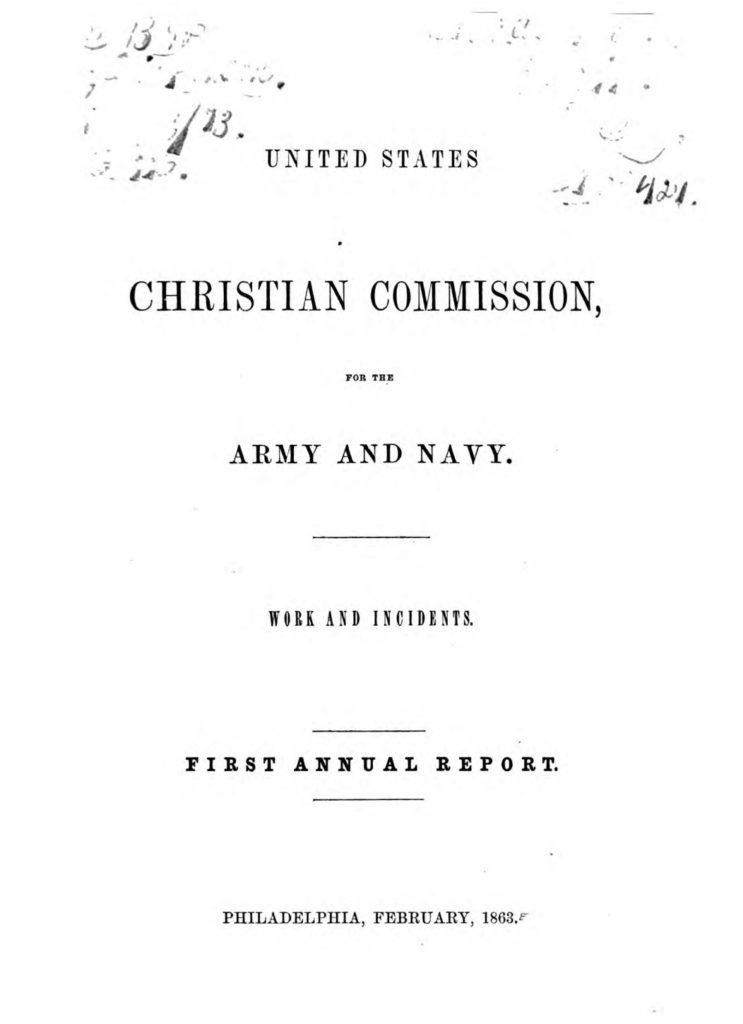

In the aftermath of Civil War battles, it was common for local townspeople to serve as first responders in the medical assistance of wounded soldiers. Aside from surgeries performed by military physicians, when men arrived at dressing stations and field hospitals, formal aid organizations such as the United States Christian Commission (USCC) provided supplementary relief services, supplies, and spiritual support.

Following the USCC’s organization at a November 1861 convention held by the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, approximately 5,000 workers served throughout the remainder of the conflict “for the purpose of systematizing and extending the Christian efforts of the various associations among the soldiers of the army.”[1]

In its three-plus years of service during “the war in the United States against rebellion,” the USCC’s mission was not borne “of the forces arrayed against each other, or of movements executed, or of victories wrought,” recalled the Rev. Edward P. Smith, USCC field secretary and official historian; “but,” he clarified, “of the forces of Christianity developed and exemplified amid the carnage of battle and the more perilous tests of hospital and camp.” Smith, who wrote a book on the organization in 1869, explained that the majority of agents were “ministers of the Gospel” whose responsibilities oftentimes required they work “in chapel-tents and fever-wards and on bloody fields,” where they professed “manly testimony for truth and [have] taken messages from the lips of death.”[2]

One of the most trying hours for the USCC occurred in September 1862. After news of the Battle of South Mountain reached Washington, D.C., on the 14th, “several Delegates, in charge of four ambulances, well filled with stores” flocked to western Maryland, reported Smith. Three days later, America suffered its costliest day of combat at Antietam, on September 17 near Sharpsburg, as a result of which 23,000 soldiers were killed or wounded.

According to Smith, USCC agents “reached Antietam in advance of other stores” to begin their work, with some gathering near Union commander Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s headquarters at the Pry House. Smith remembered, “Several…were exposed throughout the whole day of the battle, to the fire of the enemy’s artillery,” as troops engaged in bombarding and skirmishing near the Middle Bridge.[3]

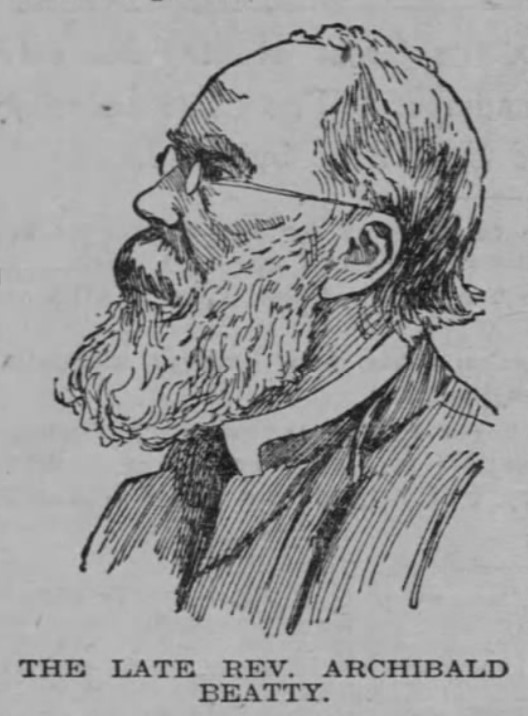

Those USCC delegates who arrived on the 17th were joined “the next day” by representatives “from Philadelphia and Baltimore via Hagerstown and Frederick,” Smith added; “and soon, over seventy were at work in the hospitals and on the field.” One man who was present during the day of battle was the Rev. Archibald Beatty, a 40-year-old Irish-born chaplain of the 34th Pennsylvania Infantry (5th Reserves).[4]

“After laboring all day among the wounded, amid the roar of cannon, with shells above and around us,…completely exhausted, I lay down on the ground among the wounded to rest,” wrote Beatty, who did not specify where on the battlefield he was located (though it was perhaps in the East Woods if he was with his home regiment). It was around 11:00 p.m., he recollected, and “I had just fallen asleep when I was aroused by the request to visit a dying soldier who desired to see me. I went and found him lying in a wagon, evidently near his end, and anxious to know the way to Christ.”

In Beatty’s words, he “raised my voice…and in the solemn stillness I prayed for him, so soon to meet the Judge, and for his comrades about him,” he noted. “As soon as that sound went upon the night air over those thousands of wounded men, every moan and groan of the sufferers who could hear was hushed.” Once he finished, “a lady sang most sweetly” a hymn, and E.N. Harris, wife of Dr. John Harris, joined Beatty at the ailing patient.[5]

Near the northern edge of the battlefield, USCC delegate James Grant was “moving around amongst the wounded of Gen. [John] Sedgwick’s Division” when his “attention was called by a disabled officer to a friend of his, badly wounded in the face, and lying out somewhere without a covering.” Using the limited light provided by his lantern, Grant came upon First Lt. Anthony Morin of Company D, 90th Pennsylvania Infantry, lying at “the foot of a wooden fence.” Grant observed, “The ball had entered one side of the cheek and passed out at the other, grazing his tongue, and carrying away several of his teeth.”[6]

“His face was horribly swollen, and he could not speak,” Grant said of Morin, who communicated only “by a nod of his head.” Under a pouring rain, “straw was procured, a bed made, and he was left for the night as comfortable as possible,” wrote Grant, who monitored the lieutenant’s progress for days by “washing and redressing wounds” and “cutting away his whiskers,” until finally “he could swallow liquids” and he was transported home to Philadelphia. At a later occasion, Grant saw Morin again, when, he testified, “Tears of gratitude filled his eyes and those of his wife; and it amply repaid me to be introduced to Mrs. M. by the gallant soldier, as ‘the man who picked me up at midnight and dressed my wound, when I had given myself up to die.’”[7]

Elsewhere, Grant aided soldiers who had been wounded in the Sunken Road while they were treated at “a farm house overlooking the bloody ground. We found them suffering and destitute…,” he asserted. “I observed an elderly soldier of a New York regiment, leaning against the barn-door” who was shot in the breast “and appeared weak from the loss of blood. He had no shirt, but had substituted it for a few blood-soaked, weather-hardened fragments of an outer coat.” The USCC supplies “were exhausted, the stock of clothing being reduced to a single shirt…,” Grant lamented. “‘You are the very man I am looking for; nobody could need this ‘last shirt’ more than you,’” he notified the New Yorker. “I handed him the shirt,” Grant claimed, “and its benevolent errand was soon accomplished.”[8]

Scores of other USCC delegates worked diligently for the betterment of mutilated and dying figures across the Antietam battlefield, including Charles Demond, who described aiding “six hundred wounded men…most of them lying in the bloody shirts in which they were wounded” and the Rev. George J. Mingins, who “was burying some poor fellows who had fallen in the battle” when a soldier admitted, “‘I ain’t no Christian, God knows; but after what we passed through…I think God saved me.’” According to Edward P. Smith’s official history of the USCC, “Hospitals for the Antietam wounded were scattered thickly over Western Maryland,” as well as in Baltimore, where the Rev. R. Spencer Vinton held a daily Bible study with Sylvester McKinley, who lost his left arm at Antietam in the ranks of the 11th Pennsylvania Reserves—until the “noble-looking” private asked that “his Testament” be “‘put…under my head’…and in a moment he was asleep with Jesus.”[9]

Letters were placed upon the desk of Chairman George H. Stuart praising the work of his USCC in the weeks after Antietam. On September 22, Joseph Thomas, surgeon of the 118th Pennsylvania wrote that he and Col. Charles M. Prevost were grateful “for the very kind and opportune assistance the Christian Commission rendered us in the sad calamity…and in fact every one connected with the Commission, aided us very materially in every instance where they could make themselves useful.” Likewise, on November 15, F. Vanderkeift, the surgeon in charge at the nearby Smoketown Hospital, acknowledged “the eminently Christian service of the Rev. Dr. [John] Sloane, at this hospital since the battle of Antietam. He has volunteered his services here, and his kindness and self-sacrifice, in ministering to our sick and wounded soldiers, are beyond all praise.”[10]

“He has been assiduous in procuring and distributing supplies from charitable associations, thereby greatly contributing to the comfort of our patients,” Vanderkeift elaborated. “As a gentleman and as a Christian minister, Mr. Sloane has won golden opinions from all with whom he has associated.”[11]

Such rhetorical praise could likely have been applied to many USCC agents as they accomplished their religious, medicinal, and compassionate deeds. After the Civil War’s most grotesque single day at Antietam—and on almost all battle grounds of the rebellion, for that matter—the underappreciated philanthropic work of the United States Christian Commission affected the lives of all who witnessed and received its delegates’ care.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Codie Eash serves as Visitor Services Coordinator at Seminary Ridge Museum, Gettysburg, and is a 2014 graduate of Shippensburg University, where he earned a bachelor degree in communication/journalism and held a minor in history. He contributes to the blog “Pennsylvania in the Civil War”; serves as a co-host on “Battles and Banter,” a military history podcast; and maintains the Facebook page “Codie Eash – Writer and Historian,” which primarily focuses on the heritage and legacy of the Civil War era.

Endnotes

[1] J. Thomas Scarf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884 (Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co., 1884), vol. 1, 831

[2] Edward P. Smith, Incidents of the United States Christian Commission (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1869), 5-6.

[3] Smith, Incidents, 41.

[4] Smith, Incidents, 41; “DR. BEATTY’S FUNERAL,” Topeka State Journal (Topeka, KS), March 8, 1904, 1; “BODY LAID IN STATE,” Topeka Daily Herald (Topeka, KS), March 8, 1904, 6; “Former Carbondale Rector,” Wilkes-Barre Record (Wilkes-Barre, PA), March 31, 1904, 4; “CANDIDATE FOR SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION,” Kansas Radical (Manhattan, KS), Sept. 5, 1868, 2.

[5] Archibald Beatty, “Songs in the Night,” in United States Christian Commission, for the Army and Navy. Work and Incidents. First Annual Report (Philadelphia, February 1863), 27.

[6] James Grant recollection, in Smith, Incidents, 42-43.

[7] Grant, in Smith, Incidents, 43.

[8] Grant, in Smith, Incidents, 43-44.

[9] Charles Demond, An Address, Delivered Before the Society of Alumni of Williams College, at Williamstown, Mass. August 1, 1865 (Boston: Press of T.R. Marvin & Son, 1865), 24; George J. Mingins, “The Faith of an Unbeliever,” in United States Christian Commission, 26; R. Spencer Vinton recollection in Smith, Incidents, 47.

[10] Joseph Thomas to George H. Stuart, Sept. 22, 1862, in United States Christian Commission, 28; F. Vanderkeift, “Another Surgeon’s Testimony,” Nov. 15, 1862, in United States Christian Commission, 29.

[11] Vanderkeift, “Another Surgeon’s Testimony,” in United States Christian Commission, 29.