Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

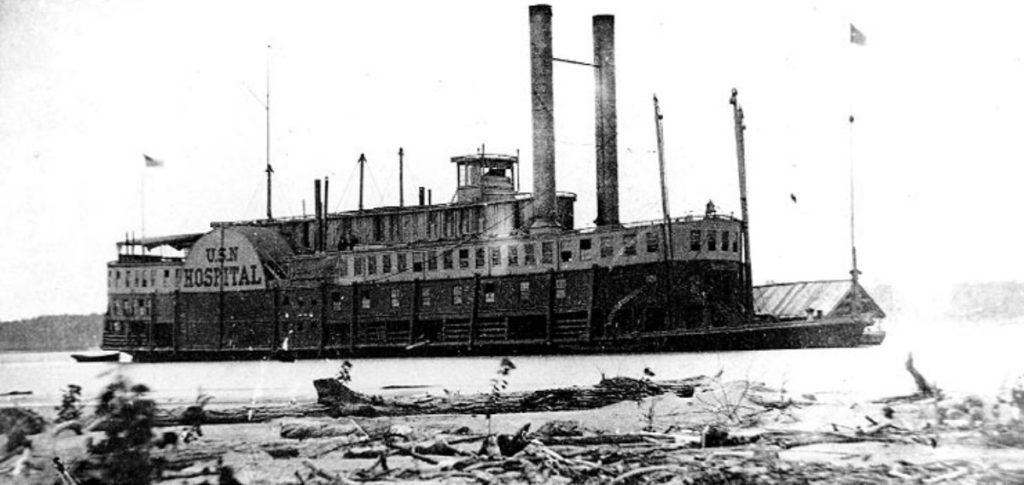

By the spring of 1864, the USS Red Rover hospital ship had cared for wounded from some of the most intense fighting of the entire war, but it wasn’t done yet.

In April 1864, the Red Rover accompanied vessels attempting to assist a US Army garrison at Fort Pillow, TN. By that time, she had served as a hospital ship at a number of famous battles near the Mississippi River, most notably at Vicksburg. By this time, white and black soldiers were being treated aboard the Red Rover. By 1864, many African American regiments had begun service in the US Army.

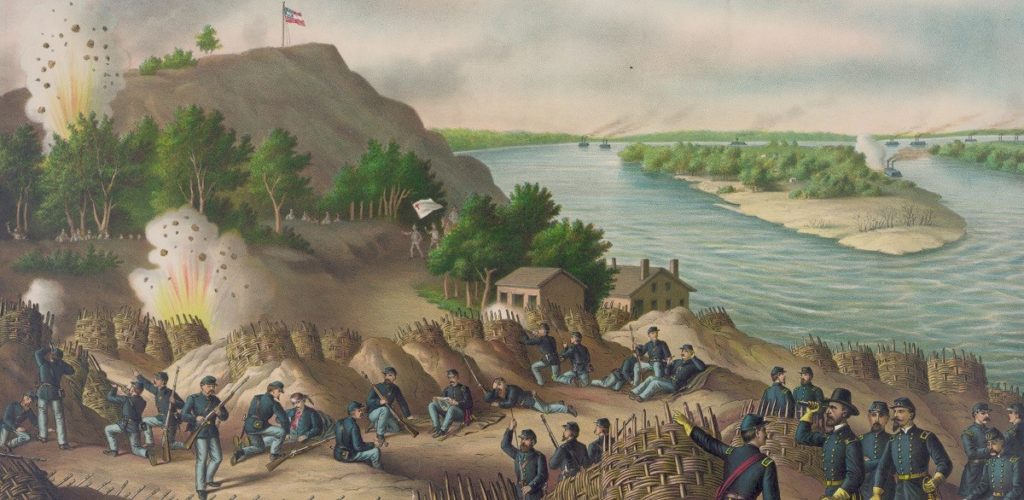

Forces under Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest attacked the garrison at Fort Pillow and over-ran it on April 12, 1864. About 600 men manned the garrison, half their number being members of the 6th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery. Forrest and Confederate forces operating throughout the Civil War did not recognize black troops as legitimate soldiers, and a number of massacres of captured black troops occurred.

The most infamous example of this behavior took place at Fort Pillow.

The Red Rover and other support vessels watched helplessly from offshore as “all the buildings round the fort and the fort itself were on fire.”

She took on 20 severely wounded Confederate soldiers following the nightmare at Fort Pillow. One observer with the squadron operating along the Mississippi on April 13, 1864 remarked on this work. “The United States naval hospital boat Red Rover landed… and provided comfortable quarters for them and a little army of assistant surgeons had their wounds quickly dressed,” he wrote.

He also observed the aftermath inside the fort, where it was alleged that Confederate soldiers provided no quarter for trapped black Union soldiers.

“The thought of the charred bodies… and the 200 or more dead bodies, mangled, dying as they did, pleading for quarter…it has so sickened me that I can write no more. I must add that in storming a fort where such desperate resistance is offered, that many, very many, must fall; but at Fort Pillow I have every evidence that instead of honorable warfare that the Confederate pursed that of indiscriminate butchery.”

Modern estimates put the number of Union dead at Fort Pillow at between 150-200. Debates continue to fester over the event.

With the Red Rover assisting those wounded from the horrors at Fort Pillow, it begs the question: What did the crew of the USS Red Rover think of the events of April 12, 1864?

On this topic, the historical record is unfortunately silent. But for those African Americans, and there were a sizeable number working aboard the Red Rover and being cared for, this event must have been earth-shaking.

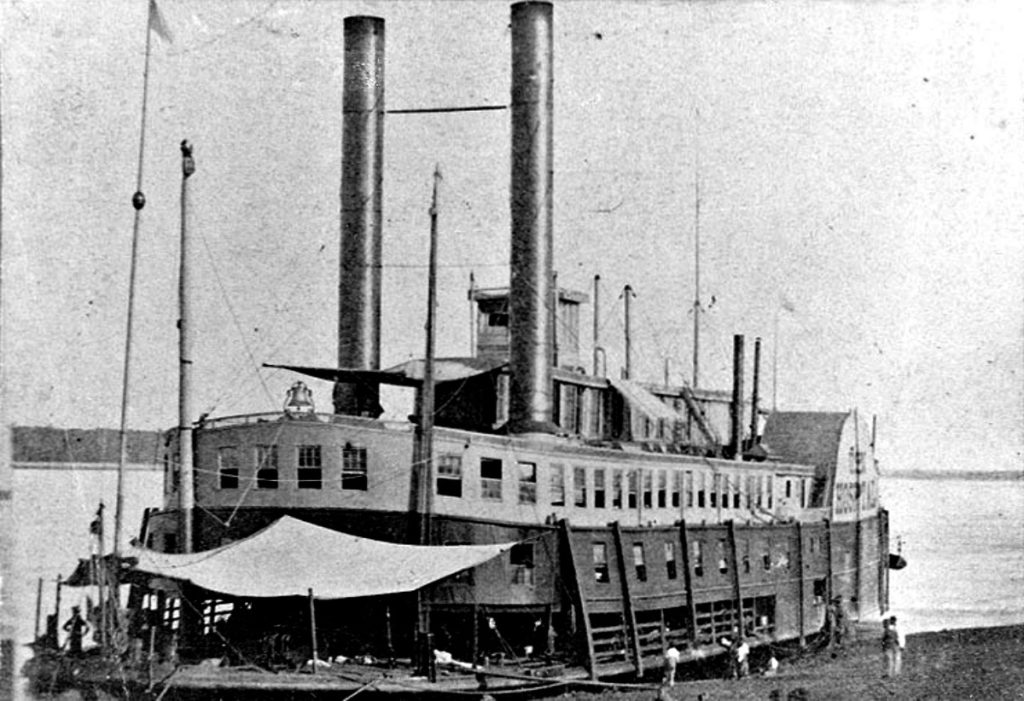

The United States Navy was the most progressive service in the military at the time. Crews in the Navy were racially integrated, unlike the units serving in the US Army. On the Red Rover and other hospital ships in the Mississippi theater, contrabands – refugees from slavery who had crossed into Union lines – worked as sailors.

Although most of the refugees who worked aboard the Red Rover were men, several also were employed on the hospital ship, becoming the first African American women to serve in the United States Navy.

Their names:

Alice Kennedy

Sarah Kinno

Ellen Campbell

Betsy Young

Dennis Downs

Ann Bradford Stokes

They were enlisted as “first class boys,” and paid wages for their work.

Ann Bradford Stokes has become the most famous of the group, and her example provides valuable insight into the lives of these navy nurses.

She was born into slavery in 1830 in Tennessee and was unable to read or write. Shortly after the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, she came aboard the Red Rover and began training with Sisters of the Holy Cross on board. There she stayed until October 1864. She met her future husband, Gilbert Stokes, aboard the ship while he was employed on the vessel.

In the years after the war, Ann Bradford Stokes was left widowed and attempted to receive a pension from the U.S. government. She had learned to read and write and proved that she had served in the service of the United States Navy for a period of 18months as a “first class boy.” In 1890, she was granted a pension of $12 a month.

The USS Red Rover continued its service with the U.S. Navy on the Mississippi River for the rest of the war and in the months that followed the cessation of fighting. She ran medical supplies and food to forts along the river systems. She evacuated the wounded from pitched battles and those stricken by sickness and disease, before tying up and providing additional bed space at a U.S. General Hospital.

In January 1865, she was sent to Mound City, Illinois and tied up at anchor, where she remained until she was decommissioned on August 12, 1865. Dr. George H. Bixby was honorably discharged a month and a half later. He had served with Red Rover from the time its service with United States forces began in June 1862.

The Red Rover, along with many of the other river steamers acquired by the United States Navy during the Civil War, was sold at Mound City, Illinois. The U.S. Navy’s first hospital ship sold for $4,500.

Over the course of her service between 1862 and 1865, the USS Red Rover treated 2,947 patients. On board, she treated the wounded and the sick from some of the most important battles of the American Civil War. But she also provided a first step for women in the United States Navy. The remarkable service of the Sisters of the Holy Cross and African American men and women illustrates that medicine in the Civil War helped shape social change in the United States. Together with the surgeons of the United States Army and United States Navy, these women nurses helped heal the sick and win the Civil War and gain a famous reputation for the ship upon which they gallantly served.

This post is the second in a two part series on the Red Rover. Click here to read part one.

Learn more from Jake Wynn, the post’s author

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Jake Wynn is the Director of Interpretation at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.