Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

“If Shakespeare had not lived, we would not have ‘to be or not to be.’ If Einstein had not lived, we might have to wait a few years for e=mc2.”[1] These are the words of Edward Dolnick in his biography of Sir Isaac Newton entitled The Clockwork Universe.

Dolnick is not denigrating the work of Albert Einstein but making a broad statement about the history of science. Science and medicine are often more about discovery than invention. Galileo did not invent heliocentrism. Nor did Einstein give light a speed limit. All these scientists revealed perpetual truths about our universe that existed whether humanity was aware of it or not.

Dolnick’s words put us in the right frame of mind to explore the most devastating, unintentional weapon of the Civil War: disease.

It has often been said that germ theory didn’t exist in the Civil War. That’s true, but germs did exist whether humanity acknowledged them or not. Just as the earth spins around the sun, gravity pulls you to the ground, and the plates of the earth move under our feet, bacteria and viruses were as present in the 1860’s as they are now.

The issue was that they were not fully understood. As Michael Flannery wrote in his book Civil War Pharmacy: A History of Drugs, Drug Supply and Provision, and Therapeutics for the Union and Confederacy: “Nomenclature then is not the nomenclature now – virus and bacteria do appear in the primary sources. A virus, however, was not understood as a microbe smaller than a bacterium capable of replicating and causing serious illness…but simply as a poison and perhaps vaguely and nonspecifically as an agent for disease transmission; bacteria were known but were just one broad group of microscopic animalcule.”[2] The term “germ” also appears as a contagious agent of disease, but was even less well defined, and the scientific community in America did not yet make the firm connection to it being a form of microbiology.

Through this ignorance of the cause of disease, physicians of the time were incapable of effectively fighting most of them. Some diseases were successfully countered through techniques we use today (the smallpox vaccine, quinine for malaria, or bromine for gangrene as examples), but either science couldn’t explain why they worked, or the wrong explanation misguided subsequent researchers away from cures for other ailments.

Disease was responsible for two-thirds of all Civil War deaths. Tragically, if we had only known about germ theory, so many deaths could have been prevented. This was an era of other impressive innovations in medicine. Medical evacuation systems, widespread use of anesthetics, and invaluable surgical experience rightly made American doctors proud of their accomplishments. This confidence, however, led to a rejection of germ theory after the Civil War.

For us to address the history of germs, we must define them. The term “germ” refers to a microorganism that causes disease. These microorganisms can be viruses, bacteria, protozoa, or fungi.[3]

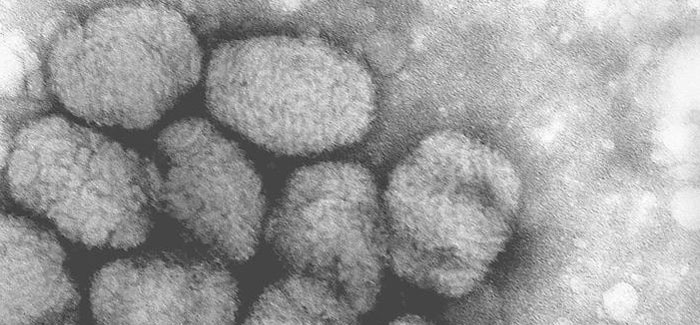

Viruses are smaller than bacteria and by replicating inside their host, cause illness. The term virus was first used in 1728 to describe something that causes a disease. It wasn’t until the 1880’s that viruses were identified as microorganisms and linked strongly to germ theory by the German Dr. Robert Koch. During the Civil War, the most significant viruses were smallpox and measles.

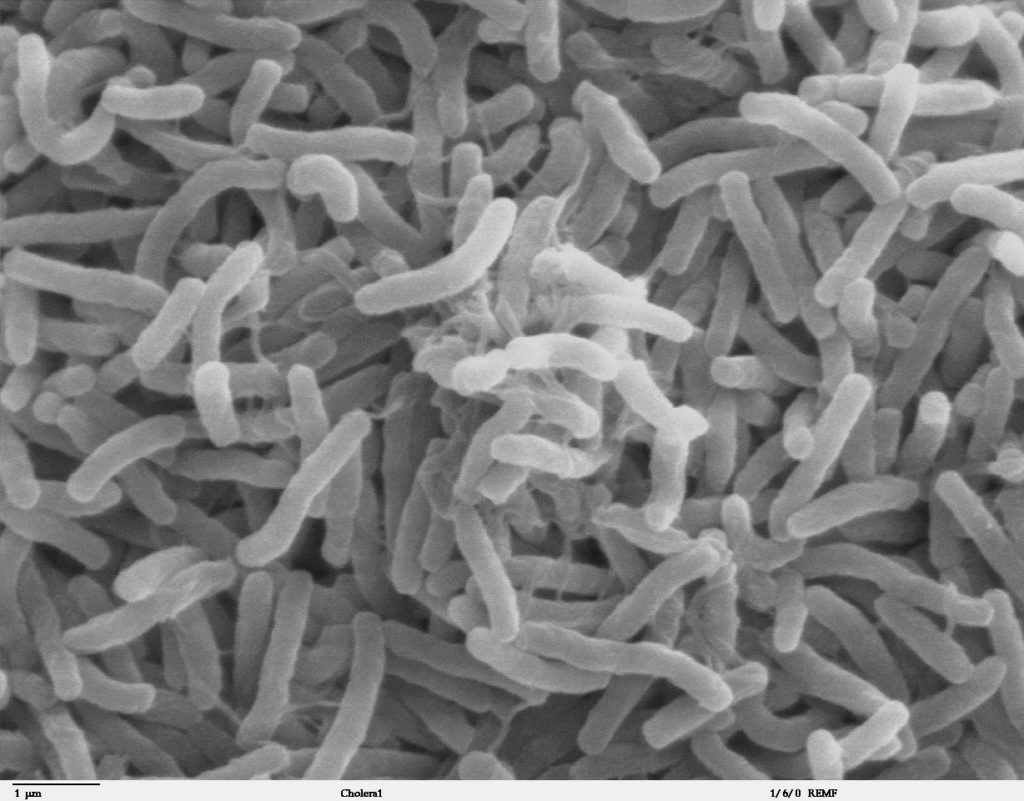

Bacteria are single celled organisms that, unlike viruses, can survive outside the body. Many are harmless, others are beneficial, and some are dangerous. Typhoid was a bacterial infection with a near 33% mortality rate during the War, resulting in sixty-five thousand dead soldiers. Cholera is another bacterial infection that was prevalent at the time and made worse by a worldwide epidemic that spread to America immediately after the war.

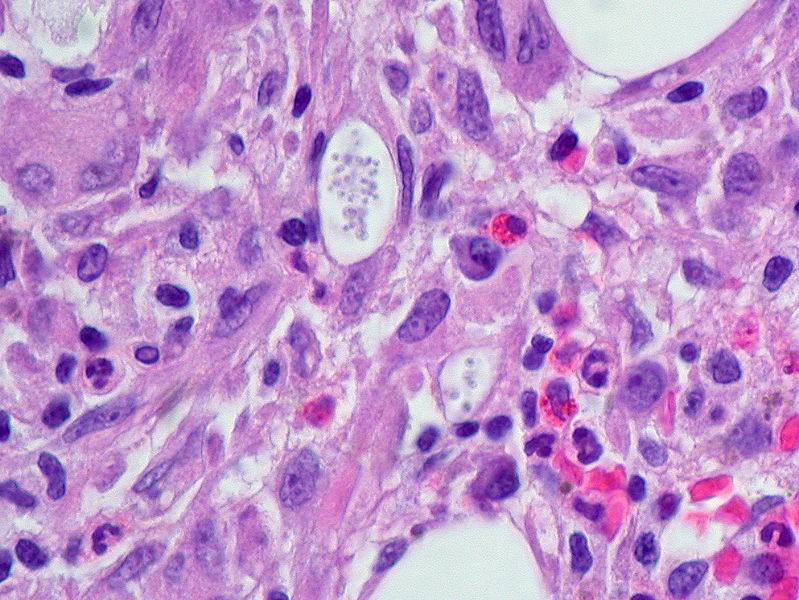

Protozoa are also one-celled organisms and are spread specifically through water. The deadliest disease of the Civil War, dysentery came in two forms: bacillary dysentery and amoebic dysentery. These come from the shigella bacteria and the Entamoeba histolytica protozoa specifically. Dysentery was the greatest danger of the Civil War, killing nearly 100,000 Rebel and Union soldiers, and probably many thousands of civilians. It’s hard to say which of the two forms of dysentery was deadlier, as they couldn’t be identified at the time, but contaminated water was a major issue in many camps.

Fungi are multi-celled organisms, and many are harmless, but not all. I don’t know of any specific fungal infections that were a major issue during the Civil War, but again, they could have been present without anyone knowing.

This brings us to another point about the Civil War and germ theory: we often separate infections from battlefield wounds when reckoning the ways that soldiers died. But any and all germ types (viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi) may have contributed to the rates of gangrene that followed wounding. This could be introduced by the environment in which a soldier was wounded, or by the invasive operations performed by physicians in the war, especially amputation. Germs significantly increased death from battlefield wounds at the same time they were killing in the peaceful camps and cities around America.

Without germ theory, physicians struggled to explain and to treat disease. The dominant theory at the time, though increasingly questioned and doubted by the 1860’s, was that of miasma. The theory of miasma held that noxious or poisonous clouds of air caused disease. This is where malaria gets its name: mal meaning “bad” and aria meaning “air.”[4]

This is a truly ancient theory, and doubts around miasma dated to antiquity. Thucydides observed an epidemic outbreak (possibly smallpox) in Athens during the Peloponnesian War around 430 BCE and through his observations recognized contagiousness of the pathogen. Contagiousness is important because it was linked to infected individuals, rather than to other environmental factors, as the miasma theory of the time would argue.[5]

Unfortunately for Thucydides and many others through the subsequent millennia, questioning a prevailing theory isn’t enough if you don’t have another explanation. Thucydides speculated that the disease was a liquid, but the technology of ancient Athens was not advanced enough to equip him with the knowledge of microbiology.

A major advancement came in the seventeenth century. The development of the microscope for the first time allowed scientists to explore the unseen world. In the 1640’s and 50’s, a German Jesuit priest named Athanasius Kircher identified microorganisms in the blood of infected patients, and appears to have been the first to directly link the presence of microorganisms to the cause of disease.[6] Various scientists in subsequent centuries also advanced this theory, but it did not gain traction until the 19th century.

Many of these scientists recognized the link between the prevention of disease and its cause. Among the most prominent of these was the Austrian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis. In 1847, Semmelweis instituted a form of antiseptic procedures that reduced mortality at the Vienna General Hospital from 18% to less than 3%. His methods were nonetheless rejected by the medical community at large, in part because he couldn’t articulate the reasons for his success.[7]

As early as 1849, the English physician John Snow was advancing germ theory, specifically to combat cholera. Five years later he effectively proved his theory by successfully ending a cholera outbreak in Soho by identifying its cause as the now-famous Broad Street Pump.

This was the pattern that would persist through the next few decades. Compelling evidence from throughout Europe was piling up, but they were not yet gathered into a comprehensive and well tested theory. Perhaps more importantly, the implications were enormous and terrifying. Doctors would have to reconcile the fact that by their ignorance they were spreading contagions and were themselves the cause of countless patients’ deaths. It would require a complete restructuring of medical practice, a huge public awareness campaign, and political will and action if it were all true. It is understandable that doctors and the public at large were wary, but every year that passed without change saw countless more unnecessary deaths.

This is the first part in a two part post on germ theory in the Civil War era. Click here to read part two.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Endnotes

[1] Dolnick, Edward, The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern World, New York: Harper, 2011,page 169.

[2] Flannery, Michael, Civil War Pharmacy: A History of Drugs, Drug Supply and Provision, and Therapeutics for the Union and Confederacy, New York: Pharmaceutical Products Press,2004, page 16.

[3] Ben-Joseph, Elana Pearl, M.D., “Germs: Bacteria, Viruses, Fungi, and Protozoa,” Kids Health for Parents, accessed May 14, 2020, <https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/germs.html>.

[4] “malaria (n.),” Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed May 14, 2020, <https://www.etymonline.com/word/malaria>.

[5] Norkin, Leonard C., “Thucydides and the Plague of Athens,” Virology: Molecular Biology and Pathogenesis, September 30, 2014, accessed May 14, 2020, <https://norkinvirology.wordpress.com/2014/09/30/thucydides-and-the-plague-of-athens/>.

[6] “Athanasius Kircher: German Jesuit Priest and Scholar,” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 28, 2020, accessed May 14, 2020, <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Athanasius-Kircher>.

[7] Ataman, Ahmet Doğan , et. al., “Medicine in stamps-Ignaz Semmelweis and Puerperal Fever,” Journal of the Turkish-German Gynecological Association, Volume 14, Issue 1, March 2013, pages 35-39, via U.S. National Library of Medicine, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3881728/>.