Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

This is the second part of a two part series. Click here to read part one if you missed it.

In late Antebellum America, early forms of hygienic practice (if not germ theory) were starting to gain traction in small circles. Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter, a renown surgeon and professor at Jefferson Medical College, was an early proponent and advocate for cleanliness. Mütter’s evangelization of hygienic practices directly translated to saving lives well after his death, amid the Civil War. Colonel Daniel Leasure commanded the 100th Pennsylvania Infantry throughout all four years of the conflict. They saw heavy service and lost 224 of their officers and men in combat. By contrast, they lost only 185 men and officers to disease. One of the reasons for this low death toll was that Colonel Leasure was a trained physician. More important than his degree, he trained under Dr. Mütter. Leasure emphasized a hygienic camp and undoubtedly saved many of his soldiers’ lives.[1]

In a similarly illustrative case, Dr. Middleton Goldsmith experimented with a form of disinfectant during his service with the Army of the Cumberland. Mortality rates from hospital gangrene were very high, over 40%, through most of the Civil War. When Dr. Goldsmith applied bromine to gangrenous wounds, the mortality dropped to below 3%. This treatment was much heralded at the time, and the Medical Department published his findings in 1863, encouraging the adoption of bromine across the Union. Even with this success, Dr. Goldsmith struggled to explain how it worked. You can find a copy of this book on display in our Frederick location.[2]

Unfortunately, most officials were not careful about cleanliness. Army camps were often filthy and hospitals were not antiseptic. Dr. Silas Trowbridge recalled two weeks of continuous operations: “Our clothes were a gore of blood and our hands so continuously in it that for most of that time they were crisped and wrinkled like a washerwoman’s after a days labor in her suds.”[3]

This is not to say that all medical facilities were disgusting. General Hospitals in cities far behind the lines, and where the focus was on recovery rather than immediate and time sensitive operations, could afford to take their time and maintain a more sanitary environment. In the 1862 Hospital Stewards’ Manual by Dr. J.J. Woodward, there are nearly forty references to cleanliness, including eating utensils, pharmaceutical supplies, bedsheets, floors, and practically everything else. This includes detailed instructions on how to clean and sharpen surgical tools.

But cleanliness is not the same thing as being antiseptic. In explaining why it was important for the tools to be cleaned, Woodward stated that it was because they would become “unfit for service” if not maintained. He does not make any connection between the cleanliness of the tools and the possibility of spreading disease. At that, Woodward instructs that the steward should clean the tools with “tepid” water, since hot water could damage the handles; porous wooden handles that could cradle germs. As you probably know, hot water is far better for disinfecting. The steward wasn’t allowed to clean the tools until “after the surgeon has done with them,” and so the same tools may have been used for multiple procedures on different patients before they were cleaned.[4]

The consequences of these understandable failures did motivate some surgeons to immediately adopt antisepsis as soon as it was articulated in Europe. Dr. George Derby, surgeon of the 23rd Massachusetts, argued that the casualties of the war proved the value of hygiene. Death by disease, he wrote, “was the direct and logical consequence of the rules of hygienic science as applied to war.”[5]

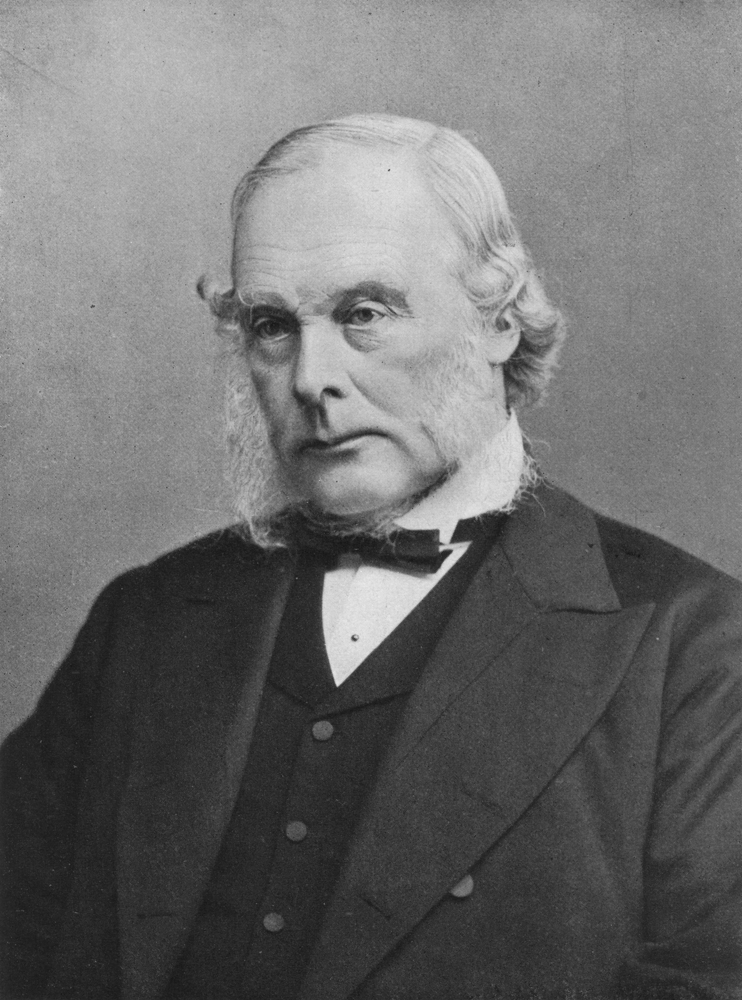

For most other surgeons, however, it was the scale of death in the Civil War, and the implication that the surgeons themselves were significant contributors to it, that slowed American acceptance of germ theory. In 1869, only four years after the conclusion of the Civil War, Scottish physician Dr. Joseph Lister published his paper proposing the first truly popular modern germ theory, building on research conducted by Frenchman Louis Pasteur that began around 1860.

Some American doctors embraced the theory and the practice of antisepsis that it required, including Dr. Woodward. Many were dead-set against it. American surgeons, with the experience that came with arguably the greatest healthcare crisis in the nation’s history, were confident and rightly so. Their use of chloroform and ether as an anesthetic agent, perfection of amputation, and professionalization were undeniably important to medical innovation. Our surgeons were perhaps the best in the world. The idea that they were killing their patients, that they were ignorant, and that upstart Europeans could tell them how to run their hospitals with risky and seemingly unproven techniques was wildly unpopular.

Dr. Henry Jacob Bigelow, head surgeon of Massachusetts General Hospital, banned antisepsis and declared it “medical hocus pocus.” This was the same hospital where the first operation under ether was performed. A very different turn from their innovative push only twenty years before.

To his credit, Dr. Lister crossed the Atlantic to deliver a lecture to a hostile American audience to try and convince them of his methods in 1876. Veteran surgeons of the Civil War, still grappling with traumatic memories of their blood covered hands, were unlikely to listen to him. One surgeon told Dr. Lister to his face that he had “a grasshopper in his head.” Samuel D. Gross, renowned army surgeon and author of the 1861 Manual of Military Surgery, spoke in the wake of Lister’s lecture: “Little, if any faith, is placed by any enlightened or experienced surgeon on this side of the Atlantic in the so-called treatment of Professor Lister.”[6]

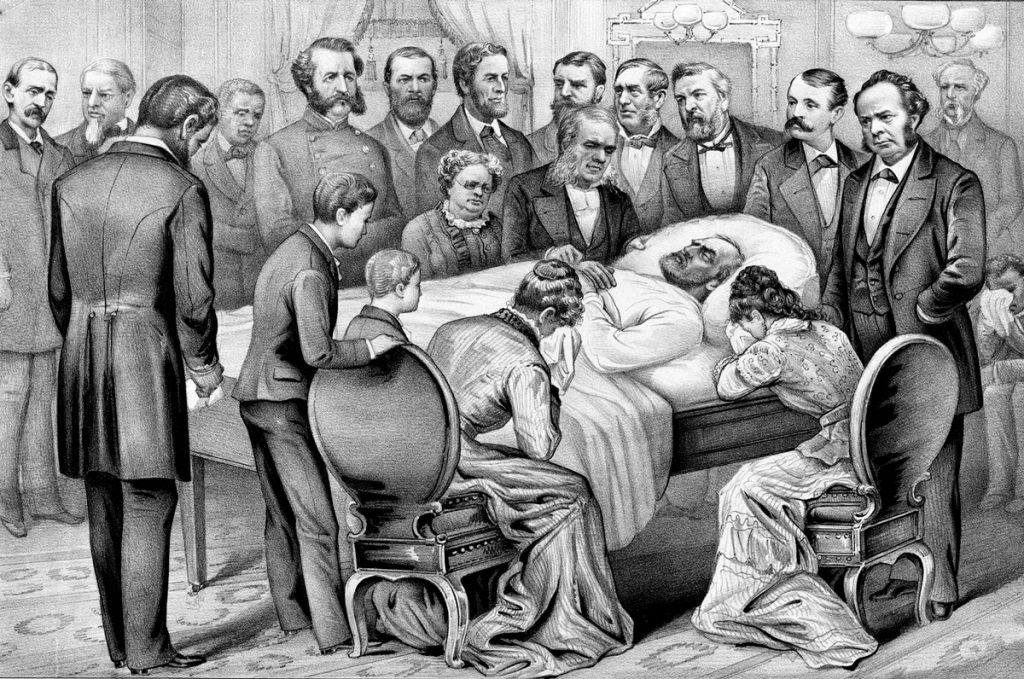

Our own Jake Wynn argues that it wasn’t until the death of President Garfield in 1881 that the American public and physicians began to turn toward germ theory. His slow and painful descent from an assassination attempt was well documented and publicized at the time. Americans read in their daily papers about the lingering and avoidable pain that Garfield suffered from infection. For more than two months the public got continuous updates about the President’s condition, and countervailing voices advocating antiseptic practices grew louder. Garfield, himself a veteran, was (in the words of Jake Wynn) the last victim of Civil War medicine.

This was also the time of rising physicians without the same blood on their hands. Newly graduated medical students who had not served in the Civil War benefited both from the innovations made by military surgeons during the conflict, and a willingness to test and utilize European antisepsis. During the 1880’s, Dr. Koch forwarded his own well-articulated germ theory, one that was more accepted within the international community. This combination made the young American surgeons the best equipped generation of physicians the nation had ever seen, and slowly the country turned to accept the scientific truth.

So, in the end, the Civil War proved a major setback to germ theory in America. The conflict unified the American medical community of the time around their remarkable innovation and enviable skill. But by spreading disease and infections that they were not aware of, the war made American physicians largely unwilling to accept their own role or to listen to outsiders who had not experienced the unimaginable trauma they lived through.

The lessons for today are pretty clear, and thankfully the world’s medical community has learned from it. Two-thirds of all deaths in the Civil War came as a result of disease. Knowledge of germ theory now enables organizations like the World Health Organization, or WHO established in 1948, to prevent the hundreds of thousands of deaths from disease seen in the Civil War. Other entities like our own Centers for Disease Control, or CDC, works to prevent the spread of disease both at home and abroad by encouraging international learning and cooperation. The National Institute of Health shares scientific research from around the globe with our own American medical professionals. We here at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine are proud to facilitate this dialogue, and we look forward to continuing it with you when you visit.

This is the second part of a two part series. Click here to be taken to part one.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Endnotes

[1] Aptowicz, Cristin O’Keefe, Dr. Mütter’s Marvels: A True Tale of Intrigue and Innovation at the Dawn of Modern Medicine, New York: Gotham Books, 2014, pages 273-274.

[2] Goldsmith, Middleton, A Report on Hospital Gangrene, Erysipelas and Pyaemia: As Observed in the Departments of the Ohio and the Cumberland, with Cases Appended, Louisville: Bradley and Gilbert, 1863, accessed May 14, 2020, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Report_on_Hospital_Gangrene_Erysipelas/vxS0AAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=germ>.

[3] Trowbridge, Silas Thompson, Autobiography of Silas Thompson Trowbridge M.D., Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 2004, page 79.

[4] Woodward, Joseph Janvier, The Hospital Stewards Manual, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1862, via the U.S. National Library of Medicine, accessed May 14, 2020, <https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101526781-bk>.

[5] Humpreys, Margaret, The Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the Civil War, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013, page 308.

[6] Fitzharris, Lindsey, The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine, New York: Scientific American, 2017, pages 214-223.