Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

One of the gray areas in oversimplified narratives of the Civil War is the treatment of enemy wounded. I have heard it in our own museum: “The enemy wounded were always treated just like their own.” Even leaving aside the obvious exceptions of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) and partisan combat in the western border states, it was not that simple.

Throughout the war, the treatment of enemy wounded was subject to what I like to call the “triage of allegiance.” Numerous written accounts reveal that it was not uncommon for both Confederate and United States medical personnel to only treat enemy wounded after their own were taken care of, and if resources were limited, they might not care for them at all.

Confederate Corporal Ephraim McDowell Anderson of the 2nd Missouri recalled discovering a mortally wounded Union officer groaning in extreme pain: “Some of the infirmary corps soon passed, and I asked them if they had any brandy or could do anything for him. Their answer was that he was too far gone to lose time with, and their brandy had given out. A few minutes after, he died.”[1] Similarly, Corporal James Scott of the 124th New York was left partially paralyzed on the field at Gettysburg. When a pair of Confederate stretcher bearers came to pick him up, their commander “told them to leave me there as I wasn’t worth bothering with.”[2] In both cases, their stated reason for leaving enemy wounded was that he would not survive anyway, but it is hard to imagine them giving such a cold and pragmatic response if it were one of their own.

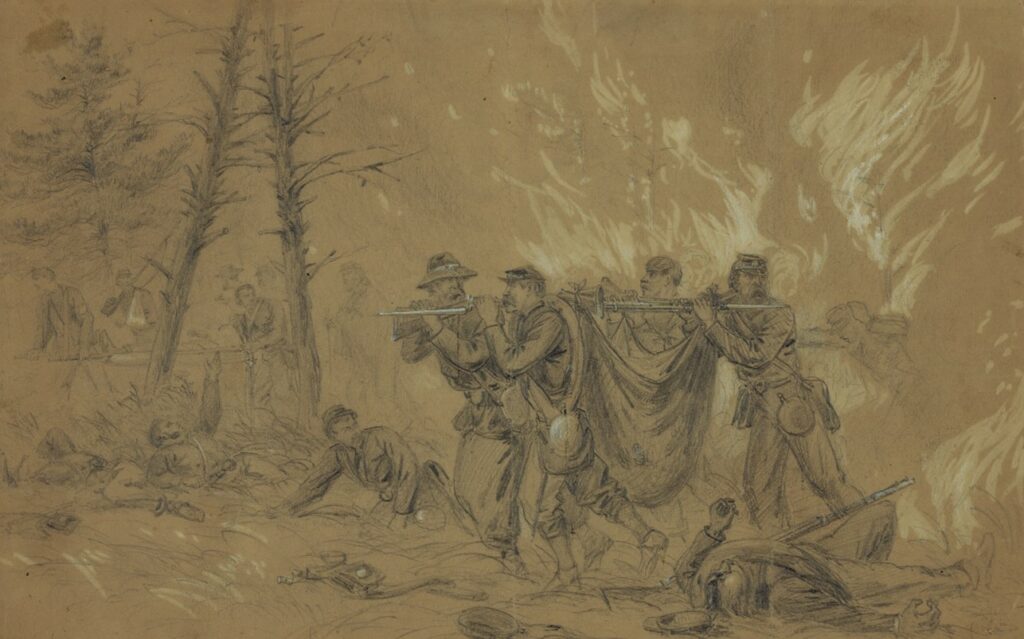

Less ambiguous was Brigade Surgeon J.T. Heard of the US Army of the Cumberland, when he reported “many rebel wounded fell into our hands, but were left for want of transportation.”[3] Private John Billings of the 10th Massachusetts Volunteer Light Artillery Battery remembered making a personal decision much like that of Surgeon Heard in the desperate whirlwind of the Battle of the Wilderness. While carrying his wounded officer off the field in a blanket, “we caught sight of a stretcher on which a wounded Rebel was lying. Some Union stretcher-bearers had been taking him to the rear when the flank attack occurred, when they evidently abandoned him to look out for themselves. It was not a time for sentiment; so, with the sergeant at one end of the stretcher and the narrator at the other, our wounded enemy was rolled off, with as much care as time would allow.”[4] The explicit and intentional sacrifice of a wounded enemy soldier to save their own is a stark admission of the triage of allegiance.

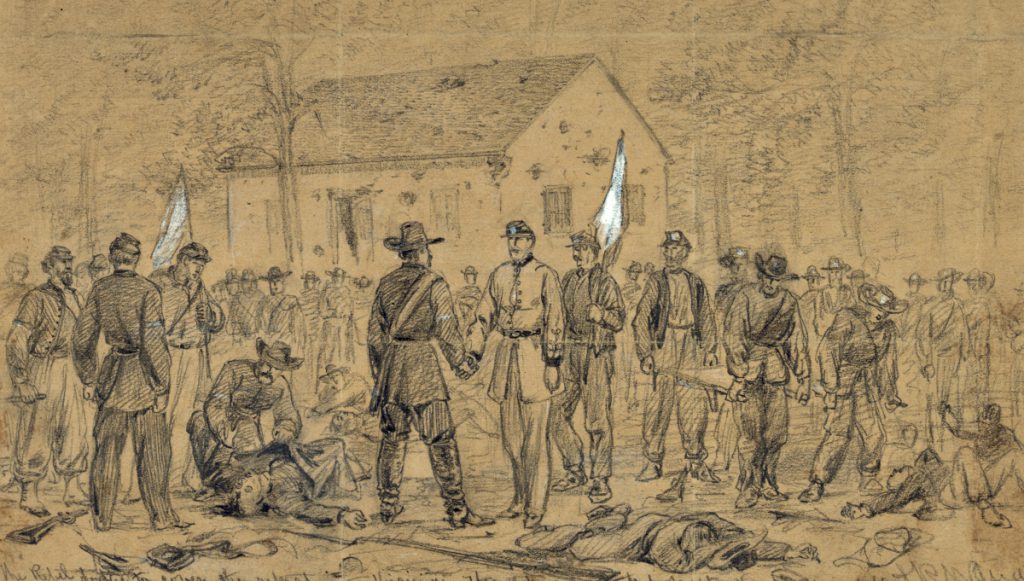

In another incident, Albert Rhett Elmore, a Confederate soldier from South Carolina in Hampton’s Legion, discovered two wounded Union soldiers huddled beneath a wagon. “They begged me to hunt up the ambulance corps and get them to come to their relief, which I did. the men, however, said: ‘Our own men first; Yankees afterwards.’ I was sorry for them, but could not aid them.”[5] Union ambulance driver R.M. Peck, writing decades after the war, echoed those words almost precisely when he remembered “The attendants were ordered to bring in the wounded only-leaving the dead to be gathered up and buried afterward-our own men first, and the rebel wounded after.”[6]

Soldiers appear to have accepted this sorting of wounded by allegiance. Private Billings, himself wounded and awaiting treatment in a field hospital observed “three wounded rebels also lay in the tent, waiting for surgical attention. Of course, they would not be put upon the tables until all of our wounded were attended to; they did not expect it.”[7]

This is not to say that surgeons universally refused treatment to enemy wounded. Captured Union surgeon Dr. William L. Nelson remembered that “when the Confederate surgeons had completed their own work they came and gave us every assistance in their power, and furnished instruments, medicine, dressings, and chloroform.”[8] Medical professionals would treat some prisoners, and often to the best of their ability, but enemy wounded must wait.

Private James Winchell of the famous Berdan’s Sharpshooters suffered exceptionally in his wait for care. Wounded at the Battle of Gaines Mill, Winchell had to wait five days for care along with hundreds of other wounded prisoners, all of whom were treated by one surgeon and one attendant. “About noon July 1st, Surgeon White came to me and said: ‘Young man, are you going to have your arm taken off, or are you going to lie here and let the maggots eat you up.[‘] I asked if he had any chloroform or quinine or whisky, to which he replied ‘no, and I have no time to dilly-dally with you.[‘]”[9] Amputation without anesthesia was incredibly rare in the war, and this is the only reliable account I’ve found in my research of such an event.

That wait probably had an impact the mortality of enemy wounded. Given sparse records regarding enemy wounded, it is difficult to say exactly what kind of impact it had, but we can say that the surgeons of the time understood what a delay in necessary operations might mean.

If an amputation was performed within forty-eight hours of receiving the wound, a soldier had a better than three in four chance of surviving the wound. If, however, the surgery was delayed until after two days had passed, the chances of survival dropped to less than two in three.[10] Such a high mortality rate after two days becomes far more important when we bear in mind that battles in the Civil War could last days, and sieges could last for months, producing mass casualties that could overwhelm medical professionals.

The urgency of evacuation and prompt performance of capital amputation was recognized at the time. In his Manual of Military Surgery, Confederate surgeon Dr. John J. Chisolm wrote, “the experience of every battlefield shows that the mortality following the amputation of limbs which require immediate operation is always less than those performed some days after the infliction of the wound.”[11] This was a lesson learned from the suffering of others in recent history. As Union surgeon Dr. Samuel D. Gross wrote: “the results of military surgery in the Crimea [1853-1856] shows that the success of amputations was very fair when performed early, but most unfortunate when they were put off for any length of time. This was the case, it would seem, both in the English and French armies.”[12]

While there were many recorded acts of compassion between both sides, the “united by compassion” narrative grew especially popular after the war during the reconciliation movement. The real story of Civil War medical care was much murkier.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Endnotes

[1] Anderson, Ephraim McDowell, Memoirs: Historical and Personal, Saint Louis: Times Printing Co., 1868, via Google Books, accessed December 11, 2019 <https://books.google.com/books?id=_H8vAAAAYAAJ>.

[2] Weygant, Charles H., History of the One Hundred and Twenty-Fourth Regiment, N.Y.S.V., Newburgh, N.Y.: Journal Printing House, 1887, page 187.

[3] Heard, J.T. , “Extracts of a Report of the Operations of the Medical Department of the Fourth Army Corps at Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville, Tennessee,” The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 326.

[4] Billings, John D., Hard Tack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life, Boston: George M. Smith & Co., 1887, page 314.

[5] Elmore, Albert Rhett, “Incidents of Service With the Charleston Light Dragoons,” in Confederate Veteran, Volume 24, New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1916, page 543, via Google Books, accessed January 24, 2020, <https://books.google.com/books?id=zsA_AQAAMAAJ>.

[6] Peck, R.M., “Wagon-Boss and Mule-Mechanic: Incidents of My Experience and Observatio in the Late Civil War,” in The National Tribune, Sep 15, 1904, page 8, via Newspapers.com, accessed March 3, 2020, <https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=14856197>.

[7] Billings, 311.

[8] Dr. William L. Nelson in McPheeters, Dr. William M., I Acted From Principle: The Civil War Diary of Dr. William M. McPheeters, Confederate Surgeon in the Trans-Mississippi, Cynthia DeHaven Pitcock and Bill J. Gurley editors, Fayetteville: University of Arkansas, 2002, page 363 n54.

[9] James Winchell, “Wounded and a Prisoner,” appendix to Capt. C.A. Stevens, Berdan’s United States sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865, St. Paul, Minnesota: Price-McGill Company, 1892, page 521, via Internet Archive, accessed February 27, 2020, <https://archive.org/details/berdansunitedsta00stev>.

[10] Bollet, Alfred Jay, M.D., Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs, Tucson: Galen Press, 2002, page 152.

[11] Chisolm, John Julian, A Manual of Military Surgery, for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate Army, Richmond: West & Johnson, 1862, page 423, via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed June 4, 2020, <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001586484>.

[12] Gross, S.D., A Manual of Military Surgery; or, Hints on the emergencies of Field, Camp and Hospital Practice, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1862, page 77, via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed June 4, 2020, <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001587977>.