Table of Contents

For every soldier who died in battle during the Civil War, another two died of disease. Improper sanitation and hygiene practices amplified the spread of sickness, especially within crowded military camps. One of the most prevailing ailments to befall blue and gray-clad troops was typhoid fever, an intestinal infection caused from the consumption of contaminated food or water or through close contact with someone already infected.[1] The Union Army diagnosed 79,462 cases of typhoid fever during the war, 29,336 of which proved fatal.[2] Among those claimed was Joseph Beall Welsh – my ancestor.

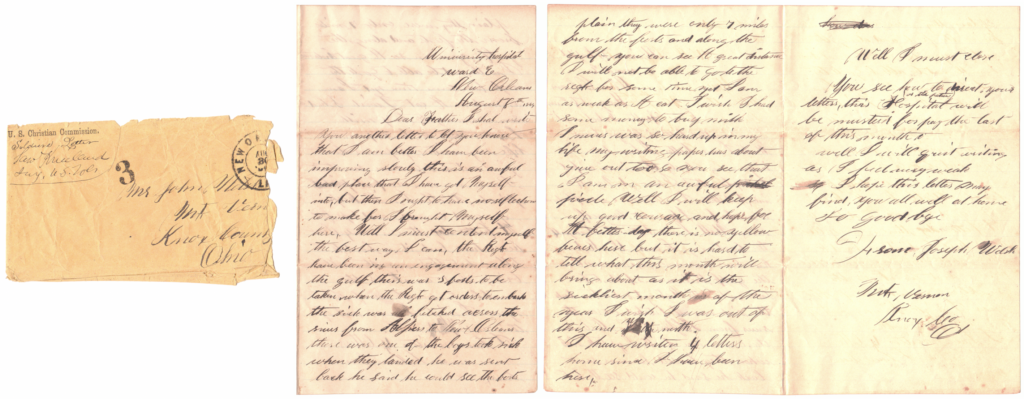

Unmarried and without children, Welsh’s enduring legacy is found within twenty-two wartime letters penned to his family, subsequently preserved for seven generations.

Born in 1847 in Knox County, Ohio, Welsh led an adventurous and rebellious life. In September 1862, two months after his fifteenth birthday, he joined over 15,000 Ohio militiamen (nicknamed “the Squirrel Hunters”) to defend the Buckeye State from a feared Confederate invasion near Cincinnati. On March 29, 1864, three months shy of his seventeenth birthday, Welsh mustered into Company A of the Ninety Sixth Ohio Volunteer Infantry (OVI) at the rank of Private.[3] Surviving wartime records cite his age as eighteen, a fib on Welsh’s part in hopes of not being turned away from military service for being underage.

Traveling by riverboat from Cincinnati, Welsh joined the other soldiers in the Ninety Sixth OVI in northwestern Louisiana near the confluence of the Red and Atchafalaya Rivers. Formed in Delaware, Ohio in August 1862, this regiment had already fought throughout many battles along the Mississippi River, most notably in the Vicksburg Campaign. By the time of Welsh’s arrival, his regiment was engaged with Confederate forces in Louisiana’s sweltering and desolate backcountry.

“It is warm enough here to cook an egg in the sand and boil water sitting out in the sun,” Welsh noted to his father.[4] “We were so far on the frontier of Southern civilization,” recalled a fellow Ninety Sixth OVI soldier, “that scarcely a trace of even the rudest efforts at agriculture or enterprise, in any form, were to be seen for many miles.”[5] Known as the Red River Campaign, this ill-fated Federal offensive ultimately redirected Welsh and his Buckeyes back to the banks of the Mississippi River.

Initially encamped near Morganza Bend, the Ninety Sixth OVI next moved to the outskirts of Baton Rouge. “Here we were for a little time, ‘freed from war’s alarms,’ the duties being very light,” recalled one of the soldiers..[6] “We have a dance here most every night,” Welsh described to his father.[7] Despite the respite from heavy combat, these Ohioans were still engaged in picket duty and the occasional skirmish. “I am willing to fight the Rebs as long as they want to fight,” Welsh boasted to his brother while arguing “we put this war down by voting.”[8]

Welsh repeatedly chronicled unsanitary scenes in his letters home. “You ought to see the Mississippi River,” he penned to his sister. “How would you like to drink that water where you could see 3 men floating down at one time…”[9] Welsh recounted to his mother the grisly discovery of human remains in their camp, once the site of an 1862 battle. “When we was fixing up our shade one of the boys of Co[mpany] D was diging [sic] a hole…He dug down about one foot and dug on to a man. They thought he was a confederate soldier…A man’s life is not thought much of down here.”[10] In another letter home, Welsh described dead Union soldiers brought to the bank of the Mississippi River. “I seen 8 or 9 men laying out with these blankets over them. I wish this war was to an end for I do not like it to see so many sick lying their [sic] and so many losing their health.”[11]

The mixing of regional and socioeconomic backgrounds within these military camps aided the spread of sickness, as each man had a differing degree of immunity and exposure to certain illnesses.[12] In an attempt to establish some primitive cleanliness measures, the Union Army instructed soldiers to boil water before use, establish their camps on high ground to allow for proper drainage, and treat their latrines a minimum of three times a day.[13] The degree to which such orders were followed is another matter.

Moreover, the selection, preparation, and consumption of untainted foods were undoubtedly compromised among hungry soldiers with meager rations. “You would not believe till you was here how it is when a person is hungry,” Welsh wrote to his mother. “I am very cautious of what I eat…I am glad I am hearty if I would happen to get down sick.”[14]

On July 20, 1864, after weeks of noncombat duty in Baton Rouge, the Ninety Sixth OVI boarded the steamer Starlight and traveled south.[15] Bound for Algiers in New Orleans, the Ohioans prepared for the upcoming maritime and amphibious assaults in nearby Mobile Bay. Upon arrival to Algiers, however, Welsh was admitted into Ward E of the Charity Hospital, affiliated with the Medical College of the University of Louisiana (now Tulane University). “I am sorry to tell you that I am sick,” he wrote to his parents.[16] Welsh had contracted typhoid fever.

Unfortunately, in 1864, there existed no treatment for typhoid fever. As historian Shauna Devine detailed, “Though physicians had made some strides in their investigations into typhoid fever before the war…a preventative vaccine and diagnostic test for typhoid fever would not be developed until the turn of the century.”[17] Patients experienced diarrhea or constipation, fatigue, respiratory distress, fever, and the development of skin lesions (often dubbed “rose spots”).

Plagued by this illness, hospitalized, and faced with the very real possibility of death, Welsh’s writings turned despondent. “I am sorry that I acted so bad when I was at home,” he wrote to his parents. “A boy to have the home that I had and go away and leave it the way that I did should be ashamed of himself…if I am blessed with the luck to go back to my dear home I shal [sic] stay their [sic] the rest of my days. I would give all I have if I could get out of the army…”[18]

Throughout his stay at Charity Hospital, Welsh scribed several letters to his parents, each offering glimpses of his state of health:

- August 1, 1864: “…I am about the same…Mother I do not like to be where there is so many sick. I can walk down stairs to my ward but I am weak. I wish I was out of this.”[19]

- August 8, 1864: “…I have been improving slowly. This is an awful bad place that I have got myself into, but then I ought to have no reflections to make for I brought myself here…”[20]

- August 18, 1864: “I have not got stout yet. I will not be able for duty for some time yet…”[21]

- August 22, 1864: “I had got almost well and took down with the fever…I am afraid that I will not get able for the service if I stay here.”[22]

Sometime after August 22, 1864, Welsh departed New Orleans. Presumably, he obtained furlough leave which afforded him the opportunity to return to Ohio by means of steamship travel up the Mississippi River. Boarding the sidewheel paddle steamer John H. Groesbeck in New Orleans, Welsh began his journey home; sadly, he did not survive. On September 22, 1864, Welsh died from typhoid fever near the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers outside Cairo, Illinois.[23]

Gone just six months into his soldiering life and a little over two months after his seventeenth birthday, Welsh is but one example of the tragic and costly nature of the war of the rebellion.

About the Author

Kyle Nappi is the great-great-great-grandnephew of Joseph Beall Welsh. An alumnus of The Ohio State University, Kyle serves as a national security policy specialist in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. He is also an independent researcher and writer of military history (chiefly the World Wars), having interviewed 4,500 elder military combatants across nearly two-dozen countries.

Endnotes

[1] “Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals – Typhoid”, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/diseases/typhoid, accessed June 29, 2021.

[2] “Typhoid and the Paratyphoid Fevers”, Office of Medical History, U.S. Army Medical Department, https://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwi/communicablediseases/chapter1.html, accessed July 1, 2021.

[3] Roster Commission, Official Roster of the Soldiers of the State of Ohio in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1866, Volume 7, (Cincinnati: The Ohio Valley Press, 1888), 287.

[4] Joseph Welsh, Letter to father, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, June 6, 1864.

[5] J. T. Woods, Services of the Ninety-Sixth Ohio Volunteers, (Toledo: Blade Printing and Paper Co., 1874), 53.

[6] Ibid, 80.

[7] Welsh, Letter from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, June 16, 1864.

[8] Ibid, July 8, 1864.

[9] Ibid, June 18, 1864.

[10] Ibid, June 23, 1864.

[11] Ibid, June 16, 1864.

[12] Michael Mahr, “Typhoid Fever – One of the Civil War’s Deadliest Diseases”, National Museum of Civil War Medicine, July 1, 2021, https://civilwarmed.321staging.com/typhoid-fever/.

[13] Richard Adler, Elise Mara, Typhoid Fever: A History, (Jefferson, McFarland & Company, 2016), 180.

[14] Welsh, Letter from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, June 21, 1864.

[15] Services of the Ninety-Sixth Ohio, 81.

[16] Welsh, Letter from University Hospital, New Orleans, Louisiana, July 29, 1864.

[17] Shauna Devine, “Typhoid Fever and the American Civil War”, Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), January 30, 2017, http://www.pbs.org/mercy-street/blogs/mercy-street-revealed/typhoid-fever-and-the-american-civil-war/.

[18] Welsh, Letter from Algiers, Louisiana, July 28, 1864.

[19] Welsh, Letter from University Hospital, New Orleans, Louisiana, August 1, 1864.

[20] Ibid, August 8, 1864.

[21] Ibid, August 18, 1864.

[22] Ibid, August 22, 1864.

[23] Official Roster, 287.