Table of Contents

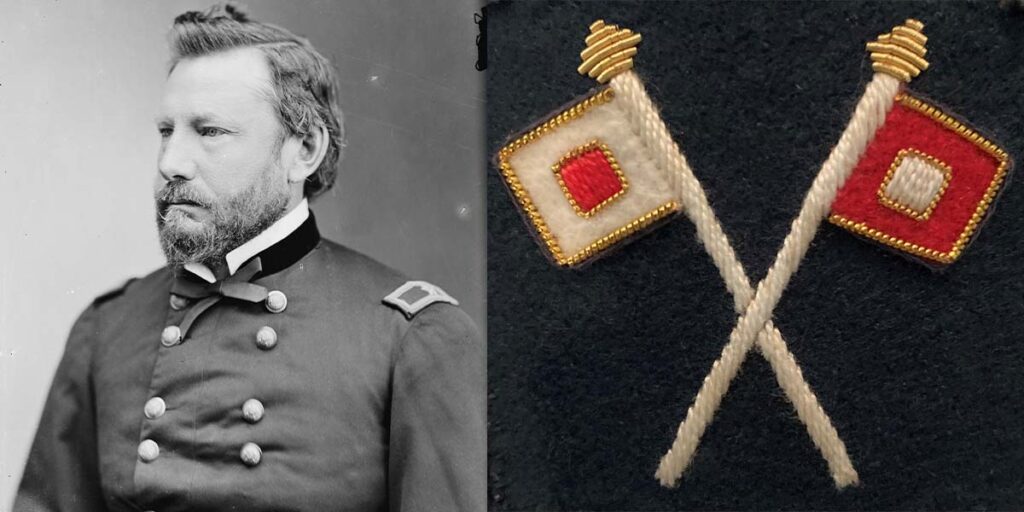

When Albert J. Myer wrote his doctoral thesis A New Sign Language for Deaf Mutes in 1851, he could not have foreseen the impact it would have on battlefield communications 10 years later. After receiving his commission as a surgeon in the United States Army in 1854, Myer was sent to Texas, where, in addition to practicing medicine, he continued his experiments in signaling. He eventually came up with a system using one flag, with the position of the flag indicating a specific number. The numbers would be combined in a sequence that would equal a letter. For example, the letter B is 1-2-2-1. In 1858, the Army expressed interest in Myer’s system, and after extensive testing, the United States Signal Corps was born, with Myer appointed as major and chief signal officer. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Myer was tasked with recruiting and training officers and establishing schools of instruction. By the end of the war, the Signal Corps consisted of almost 300 officers and 2,500 soldiers.

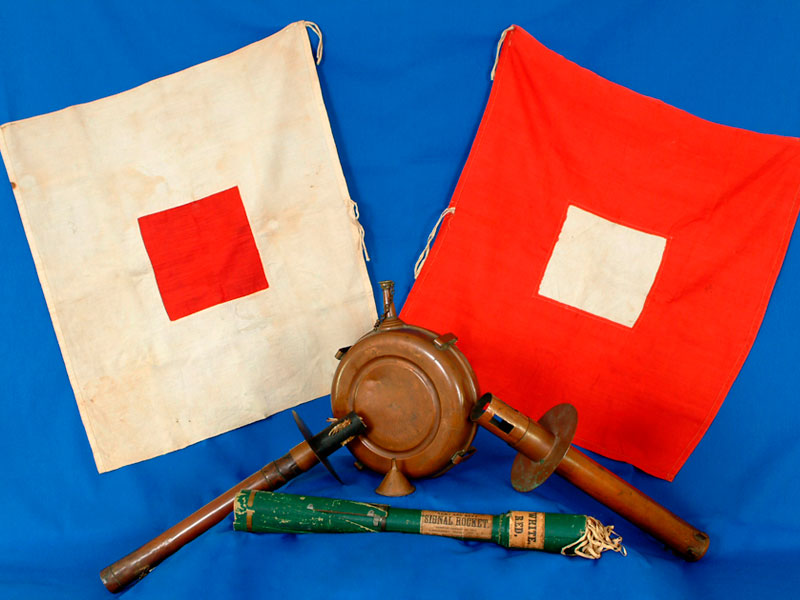

To serve in the Signal Corps, candidates had to pass a strict exam consisting of reading, writing, arithmetic, surveying, and topography. Once chosen, the soldier was assigned to a signal party, usually consisting of one officer and several privates. The officer was responsible for encoding and decoding signals, while the privates would wave the flag and observe incoming messages. The soldiers were all mounted and could move quickly from place to place. The equipment they needed, including several different sizes of flags, torches for night signaling, and telescopes, could be quickly packed up and transported on horseback. The average distance that signals were sent and received was from 8 to 15 miles, depending on weather conditions. Stations would often be set up in a relay system, ending at a location with access to a telegraph.

One of the earliest uses of the Signal Corps was at the battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. Several signal stations were established in the Sharpsburg, Maryland area, including one on Elk Ridge, and one at the Pry House, which was used by Union General George McClellan. These stations sent messages to commanders on the field and observed and reported the movements of the Confederate army. The most important signal of the battle was sent to General Ambrose Burnside warning of the approach of Confederate General A.P. Hill’s troops from Harpers Ferry. Information on the progress of the battle was relayed to Washington D.C. via a series of stations set up from the Pry House to South Mountain to Middletown to Frederick, Maryland. Once received in Frederick, the message was then telegraphed to Washington. Using this system, President Lincoln was able to receive updates from the battlefield in just 30 minutes.

After the battle of Chancellorsville, in May 1863, the Signal Corps started to employ cipher disc coding systems when sending messages. The Confederate army had the same signal system, and it was not uncommon for each side to read the other’s messages. Two discs made of brass or cardboard were used. One disc was inscribed with the alphabet and the other with the numeral combinations that represented letters. When the disc was rotated, the alignment of numbers and letters could be changed. The Union often changed its discs daily, while the Confederate army rarely switched. As a result, the Union code was never cracked.

During the battle of Gettysburg, in July 1863, the Signal Corps established a station on Little Round Top and reported the movements of Confederate troops. Due to their high visibility, the signal party suffered severe casualties from Confederate artillery and sniper fire.

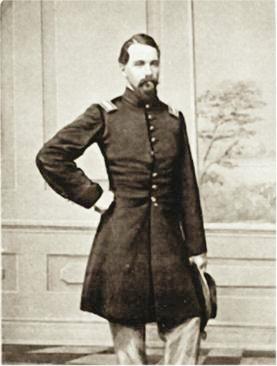

The Signal Corps continued to relay information after the battle, when they followed the retreating Confederates through Pennsylvania, Maryland, and back into Virginia. 2nd Lt. Julius M. Swain was ordered to establish signal stations in the Washington County, Maryland area. Swain related his experience in a letter to a friend:

At 12, Capt. D. [Daniels] came on and ordered me with him to front where we ran a station all day and night. Our friends sent us several remembrances in the way of shot and shells which made me feel a little white at times but no one was hurt in our party.

Next morning Capt N. [Nicodemus] left me on station but learned that the rebs were in fine retreat on Hagerstown and I followed with party, arriving there at 10am just as the devils were leaving town and shelling our advance in fine style.

By 12M I had a grand station where I could see all the enemy’s movements on our right and the flag was not exposed to his sharpshooters.

Remained there till the morning of the 14th and sent several messages some of which were telegraphed to Washington and most of them were sent either to Gen Meade or the Corps commanders.

On my way to Williamsport on the morning of the 14th captured three rebs representing No. Carolina, Va., Georgia. With immense courage and a deal of strategy I surrounded three as willing captives as ever surrendered. One had a loaded carbine which I took and shall send home if possible.

They were tired of war and had not been happy for a long time till in the hands of their enemies. I treated them just as I would any man and on our arrival in W. [Williamsport] handed them over to the Provost M. [Marshal] . . .

The Signal Corps continued to play an important role for the rest of the war, taking part in all the major battles and covering General Sherman’s march to the sea. After the fall of Richmond, Virginia in April 1865, the first Union message was sent by the Corps from the roof of the Confederate Capitol building.

Albert J. Myer was eventually promoted to the rank of Brevet Brigadier General in recognition of his role in forming the Signal Corps. Because of Myer’s interest in storm telegraphy, the Signal Corps was authorized by the United States Congress in 1870 to conduct “meteorological observations at the military stations in the interior of the continent and at other points in the states and territories of the United States, and for giving notice on the northern lakes and seaboard by telegraph and signals of the approach and force of storms.” Thus began the U.S. Weather Bureau, now the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In 1873, Myer proposed establishing a system of communication around the world between weather stations which eventually became the World Meteorological Organization. Myer headed the Signal Corps until his death in 1880.

Today, the U.S. Signal Corps is still an important part of the Army. Instead of flags and torches, soldiers use radios and GPS satellite systems. Despite the change in technology, the Corps still plays an essential role in facilitating communications and gathering information—carrying on the traditions first established in the Civil War.

Artifact exhibits on the Signal Corps in the Civil War can be found at:

The National Cryptologic Museum, https://www.nsa.gov/museum/

The Ochs Memorial Observatory at Lookout Mountain – Chickamauga/Chattanooga National Military Park, https://home.nps.gov/chch/learn/lookout-mountain.htm

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, N.H. She is Director of Communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield, a Historical Interpreter at South Mountain State Battlefield, and an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises. Discovering her ancestor, 2nd Lt. Julius M. Swain, sparked her interest in the U.S. Signal Corps.

SOURCES

Army Heritage Center Foundation. “Keeping the Lines Open: The U.S. Army Signal Corps.”

Brown, J. Willard. The Signal Corps in the War of the Rebellion. U.S. Veteran Signal Corps Association, 1896.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, https://vlab.noaa.gov/web/nws-heritage/-/the-first-synchronized-weather-observations

Ibid., https://vlab.noaa.gov/web/nws-heritage/-/a-brief-history-of-signal-flags

Signal Corps Association 1860-1865. www.civilwarsignals.org

Swain, Julius M. Personal letter July 19, 1863. Collection of Julius M. Swain, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

U.S. National Park Service. “The Signal Corps at Antietam Battlefield,” www.nps.gov/anti/learn/historyculture/signal.htm