Table of Contents

It has often been said that the recruits of the Civil War were only required to have two opposing teeth so that they could open the paper cartridges used to load their rifles. Certainly, for the United States, they needed much more than that.

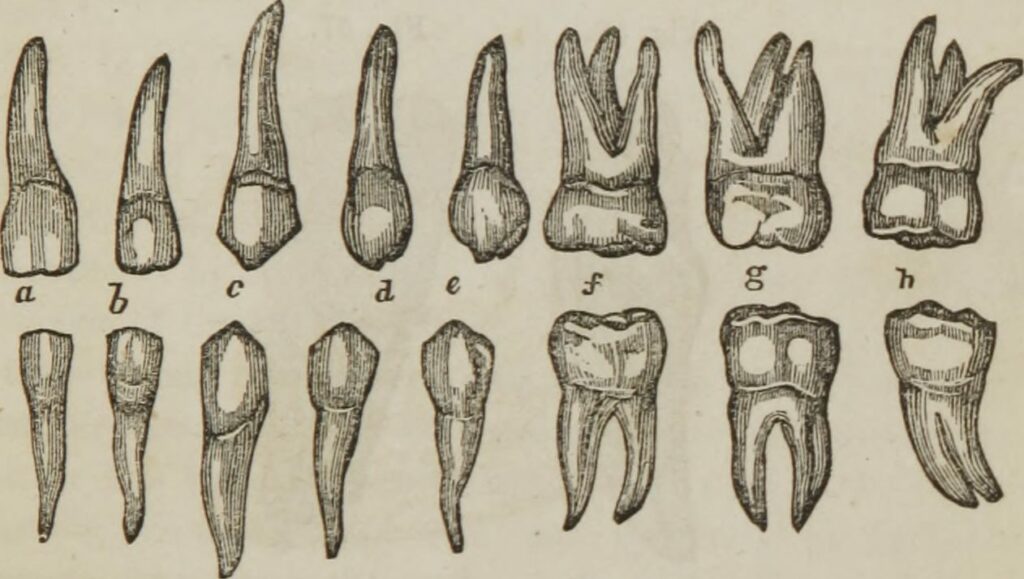

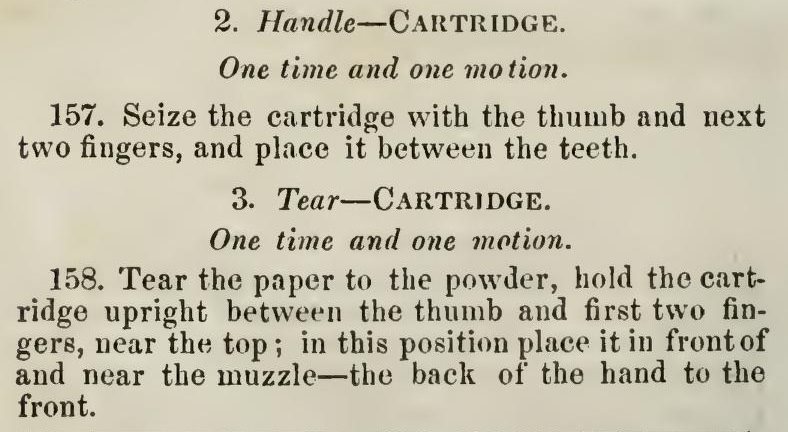

Having opposing teeth was undeniably important for loading and firing the rifles of the era. Before the war even began, Surgeon Charles Tripler declared the “loss of the incisor and canine teeth of both jaws” disqualifying for potential recruits.[1] The wartime Revised Regulations of the United States Army, as related in Dr. John Ordronaux’s Manual of Instructions for the Military Surgeons on the Examination of recruits and Discharge of Soldiers, emphasize the importance of a soldier having “a sufficient number of teeth in good condition…to tear his cartridge quickly and with ease. The cartridge is torn with the incisor, canine, or bicuspid teeth.”[2]

In his Manual of Instructions for Enlisting and Discharging Soldiers, Assistant Surgeon Robert Bartholow explains that those teeth were not the only ones necessary for military service, going so far as to argue that “if a man have lost the incisors only; it will not constitute a ground of exemption or rejection.” Bartholow points out, rightly, that “a man anxious to load his piece will find means to do it, if he have no teeth, though he may not accomplish it with rhythmical order and precision.”[3] Tripler had similar thoughts:

The soldier must again have teeth of some description, strong enough to tear his cartridge. This is usually done with the incisor and canine teeth. But if the bicuspid and two of the molars in both jaws upon the right side remain and are sound, we think this may be done as conveniently as with the incisor and canine. The instructions…in the tactics, merely prescribe that it is to be put between the teeth, without specifying the particular teeth by which it is to be torn.[4]

There were other concerns in enlisting soldiers with poor teeth, of which tearing cartridges was only one. General dental health was vital in recruits to the army. In the Revised Regulations, examining surgeons were instructed to reject recruits who had “total loss of all the front teeth, the eye-teeth, and first molars, even if only of one jaw.”[5]

A recruit needed “a sufficient number of teeth in good condition to masticate [chew] properly.”[6] This reasoning was echoed elsewhere in those same regulations “where the loss of teeth is so great that, if the man were restricted to solid food, he would soon become incapacitated for military service.”[7] Bartholow agreed that “the proper mastication of food is interfered with” if a recruit lacked enough teeth in healthy condition.[8] As Tripler states, “hard bread, tough beef, and salt pork, require good molars for this purpose. The incisor and canine teeth are not adapted to this end, i.e., without the aid of some of the molars.”[9]

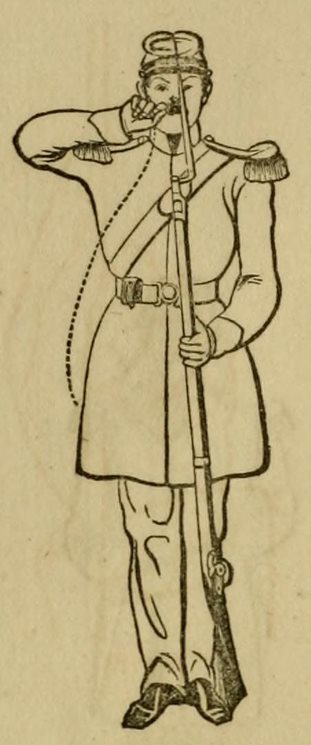

Bartholow also warned that merely having teeth was not enough. If those teeth were in poor condition, they may be a symptom of other conditions and were likely to deteriorate over the course of service. “A carious [decayed] condition of the teeth, and loss of the incisors and canines, are causes of rejection…because they are evidences of a depraved state of the general system…If the loss was occasioned by caries and the remaining teeth begin to decay, he will probably prove useless if enrolled or enlisted.”[10]

Confederate sources notably neglect teeth as necessary for medical examinations. In the Regulations for the Medical Department of the C.S. Army, the only note that hints at dental examinations is that the surgeon ensure the recruit’s “speech [is] perfect.”[11] As the war progressed, even this requirement was relaxed. In 1863, Surgeon General Samuel Moore explicitly listed speech impediments as no barrier to admitting conscripts.[12] Dr. John J. Chisolm, in his Manual of Military Surgery, mentions that the peacetime U.S. army did reject recruits for “loss of teeth,” but does nothing more to explore or explain how many teeth or which ones should be present.[13] At least in one case, inability to chew solid food was not enough for a compulsory discharge. Farmer Dulaney, a private in the Army of Tennessee’s Orphan Brigade, “was so afflicted that he might have been honorably discharged at any time…his teeth and a portion of his jawbones had been destroyed by the effects of mercury, and his mouth was so dreadfully distorted that he could take only some kind of soft food, with a spoon; and a great portion of the rations regularly issued to the troops was to him useless.” Predictably, Private Dulaney’s condition was exacerbated by the difficult life of a soldier and inedible rations, and he died of disease in January 1864.[14] Throughout the conflict, no apparent effort was made by the Confederacy to regulate the admission of recruits for dental issues.

The myth of requiring only two opposing teeth is thoroughly rejected in the original sources. In the United States, soldiers needed multiple healthy teeth to tear cartridges and chew hard food, and unhealthy teeth were grounds for rejection regardless. In the Confederacy, little care was taken to determine what dental conditions were worthy of rejection or discharge. In the end, nothing whatsoever exists in the primary sources to suggest that either side utilized or adhered to a regulation stating that two opposing teeth were all that was required to join the military

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is the Membership and Development Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is also a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Endnotes

[1] Tripler, Charles S., M.D., Manual of the Medical Officer of the Army of the United States, Part I: Recruiting and the Inspection of Recruits, Cincinnati: Wrightson & Co., 1858, page 59, via Google Books, accessed November 11, 2021, < https://books.google.com/books?id=ptY6JNu9dcgC>.

[2] Ordronaux, John, M.D., Manual of Instructions for the Military Surgeons on the Examination of recruits and Discharge of Soldiers, New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1863, page 210, via HathiTrust, accessed November 11, 2021, <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101023844085>

[3] Bartholow, Roberts, A.M., M.D., A Manual of Instructions for Enlisting and Discharging Soldiers, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1863, pages 55-56, via the U.S. National Library of Medicine, accessed November 11, 2021, <https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/bookviewer?PID=nlm:nlmuid-62430200R-bk>.

[4] Tripler, Manual, 60.

[5] Annual Report of the Secretary of War, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1865, page 77, via Google Books, accessed November 8, 1865, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/Report_of_the_Secretary_of_War_which_Acc/EMVOAQAAMAAJ>.

[6] Ordronaux, Manual, 228.

[7] Annual Report, 75.

[8] Bartholow, Manual, 55.

[9] Tripler, Manual, 60.

[10] Bartholow, Manual, 55-56.

[11] Regulations of the Medical Department of the C.S. Army, Richmond: Ritchie & Dunnavant, 1862, page 11, via Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, accessed November 11, 2021, <https://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/regulations/regulations.html>.

[12] Hasegawa, Guy R., Matchless Organization: The Confederate Army Medical Department, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 2021, page 164.

[13] Chisholm, J. Julian, M.D., A Manual of Military Surgery for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate States Army, Second Edition, Richmond: West & Johnston, 1862, page 15,via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed November 11, 2021, <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=dul1.ark:/13960/t0vq3q051>.

[14] Thompson, Ed Porter, History of the Orphan Brigade, Louisville: Lewis N. Thompson, 1898, page 566, via Google Books, accessed November 11, 2021, <https://books.google.com/books?id=Y6odAQAAMAAJ>.