Table of Contents

Dr. Jonathan Letterman, Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac beginning in 1862, is regarded as the father of battlefield medicine. His colleague and Surgeon General of the Army beginning in 1862, Dr. William Hammond, is one of the pivotal figures in the development of the modern hospital. Much like Letterman, Hammond recognized that Army medicine needed to change and used his influence throughout his service in the Civil War to enact those changes.

William Hammond, born near Annapolis and raised in Pennsylvania, was the son of a physician who a young William looked to for inspiration.[1] He received his medical degree in 1849 from the University of New York Medical School and joined the army as an assistant surgeon shortly after. For the next eleven years, Dr. Hammond served with the Army primarily in Kansas and New Mexico while he was studying the effects various poisons had on the nervous system and collecting a wide variety of botanicals. This side interest then opened up a teaching position for him in 1860 at the University of Maryland.

This position would be short-lived as less than a year after he began his teaching career, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in South Carolina which ignited the Civil War. Dr. Hammond rejoined the Army but due to his hiatus, had to start fresh as an assistant surgeon.[2] Shortly thereafter, Dr. Hammond was promoted to be a camp inspector and hospital administrator due to his prior eleven years of experience. It was here that he began to update an archaic medical system that was still clinging to old-fashioned theories of medicine. Inspired by the works of the famed nurse Florence Nightingale, Dr. Hammond wanted to build hospitals that emphasized sanitation. His work in attempting to reformat the entire Union hospital system while working with Dr. Letterman to reform and create the Ambulance Corps drew the attention of both General George McClellan and the US Sanitary Commission. At about the same time, the acting Surgeon General of the Army, Clement Finley, was removed from office. President Abraham Lincoln, on the recommendation of Sanitary Commission officials, then appointed Dr. Hammond to the position as the 11th Surgeon General of the Army in 1862.[3] Dr. Jonathan Letterman would also rise to become the Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac the same year and the two of them would attempt to completely change Army medicine for generations to come.

Early in his tenure as Surgeon General, William Hammond issued Circular No. 2 in May of 1862. This act authorized the establishment of the Army Medical Museum today known as the National Museum of Health and Medicine.[4] The purpose of Circular No. 2 was to direct medical officers to “diligently collect and forward to the office of the Surgeon General all specimens of morbid anatomy, surgical or medical, which may be regarded as valuable.”[5] One of those specimens was the leg of Union General Daniel Sickles, who had it shot off by a cannon on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Sickles’ leg was transported to the museum in a barrel of liquor, which was common for the time. Sickles would periodically visit his leg in the museum along with many other soldiers with lost limbs on display.

While serving as Surgeon General, his office began to compile medical reports from surgeons and hospitals across the nation. Circular No. 2 created the environment for reports, statistics, and interesting and unusual cases to be compiled in the most extensive medical texts of the Civil War, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, a multi-volume several thousand-page work with about everything you can think of in regard to Civil War Medicine. This text would not be completed until after the conclusion of the Civil War, but Dr. Hammond was the man in charge of beginning the process to create this piece of work. Future surgeons and medical schools would use the collection of cases to teach the lessons learned from the outbreak of war and prepare future doctors.

The numerous surgeons Hammond passed over to attain his new position did not like some of the changes he implemented. Surgeon General Hammond would regularly send inspectors to hospitals to make sure that the sites were keeping up with sanitation and ventilation. Both of these were proven by Florence Nightingale to reduce infection and disease rates in hospitals. He also set a minimum age requirement and minimum skill requirements for all surgeons.[6] Hammond’s quick and decisive action in reforming the hospital system improved the level of care soldiers would receive and reduced the mortality rates within hospitals, “under Hammond’s new system, the sick and wounded were better cared for than they ever had been before, and the mortality rate was lower than in the experience of any prior army.”[7] Drawing from his newfound experience managing Civil War hospitals, Hammond wrote A Treatise on Hygiene: With Special Reference to the Military Service in 1863.

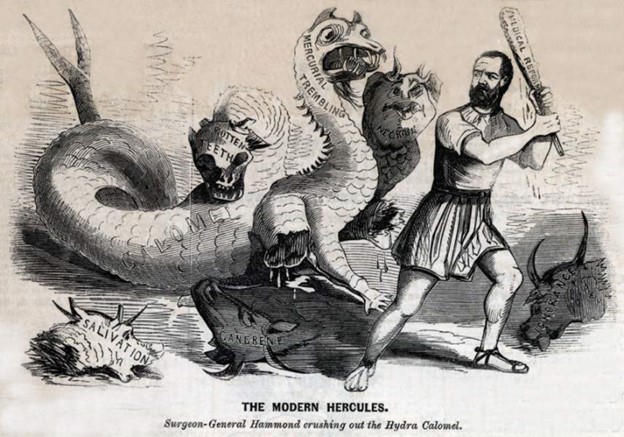

Also in 1863, Dr. Hammond would make a decision that would cost him his job as Surgeon General. He did not make any grand mistake or major tactical error which would cause a commanding general to lose their job, Dr. Hammond simply wanted to have US Army surgeons use less mercury in their medicines. Hammond began this mission by removing mercury-based drugs such as calomel, blue mass, and others from the supply chain. Calomel was used to treat a wide variety of ailments commonly seen throughout the Civil War despite it almost always doing more harm than good. This action caused immense dislike between doctors, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and Dr. Hammond. After being ordered to review Army hospitals in the South and West, Hammond returned to Washington where he faced a court martial and lost his case in August of 1864. Hammond had become a villain for a short while after his court martial “The [New York] Times also claimed that Hammond had ‘stooped to the level of the lowest shoddy knave’ and went on to state, ‘he will be remembered only to be loathed.’”[8]

The cartoon appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 1, 1863.

The New York Times would be very wrong about Dr. Hammond as he moved his practice to New York following his court martial and worked closely with Bellevue Hospital to study neurological disease and mental health issues as it was still a fairly new field of study. He became one of the first physicians in America to study both neurological disease and mental health diseases, and in 1871, he published what would become his most famous work, A Treatise on Disease of the Nervous System. He would also go on to become a founding member of the American Neurological Association and continue to impact the medical field in this position.

The Civil War was an era of medical revolution which we still reap the benefits of today. One of which is the hospital system developed by Dr. Hammond as he would improve upon the already successful hospitals seen throughout Europe over the previous decade. Dr. Hammond should be remembered as a pivotal figure in the evolution of American medicine and hospital development. His ideas sparked a medical revolution in the years before germ theory by attempting to reduce the use of one of history’s most harmful medicines. Both Dr. Letterman and Dr. Hammond saved countless lives with their revolutionary ideas, and we can still see them in action in our everyday lives 160 years later.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021.

Endnotes

[1] “William A. Hammond (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d. https://www.nps.gov/people/william-a-hammond.htm.

[2] “Hammond, William Alexander (1828-1900).” Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. University of Alabama at Birmingham, n.d. https://library.uab.edu/locations/reynolds/collections/civil-war/medical-figures/william-alexander-hammond.

[3] “Dr. William A. Hammond.” American Battlefield Trust, n.d. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/dr-william-hammond.

[4] “Dr. William A. Hammond.” American Battlefield Trust, n.d. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/dr-william-hammond.

[5] Devine, Shauna. Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017. Pg 22.

[6] “Dr. William A. Hammond.” American Battlefield Trust, n.d. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/dr-william-hammond.

[7] “Hammond, William Alexander (1828-1900).” Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. University of Alabama at Birmingham, n.d. https://library.uab.edu/locations/reynolds/collections/civil-war/medical-figures/william-alexander-hammond.

[8] Carrino, David. “The Medical ‘Rebellion’ within the Union Army.” The Cleveland Civil War Roundtable, June 15, 2021. https://www.clevelandcivilwarroundtable.com/the-medical-rebellion-within-the-union-army/.