Table of Contents

During a campaign our stocks of medicines were necessarily limited to standard remedies. These were opium, morphine, Dover’s powder, quinine, rhubarb, Rochelle Salts, Epsom salts, castor oil, sugar of lead, tannin, sulphate of copper, sulphate of zinc, camphor, tincture of iron, tincture of opium, camphorate, syrup of squills, simple syrup, alcohol, whiskey, brandy, port wine, sherry wine, etc. – Dr. Charles B. Johnson, a Union regimental medical steward[1]

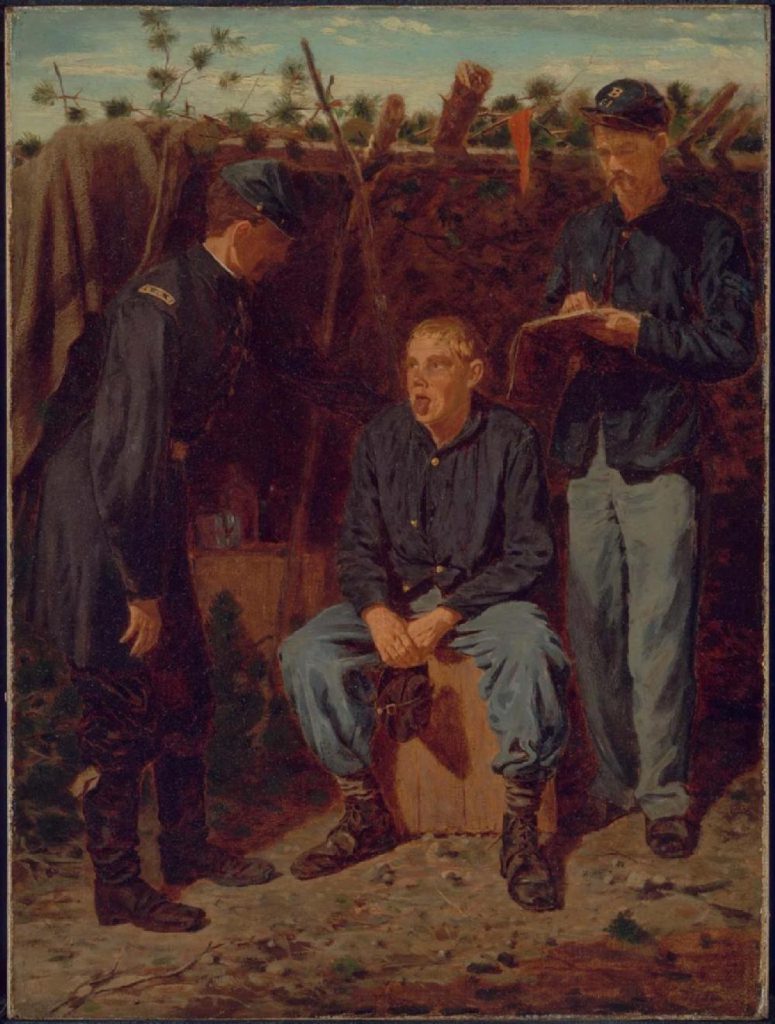

While the Civil War saw many medical innovations that would benefit humanity, including the widespread use of anesthesia and the development of battlefield medicine, there were some aspects of medical care that today are questionable at best. These included medicines that if given today, would certainly raise an eyebrow among doctors. Let us examine some of these “bad medicines” and their potentially harmful effects.

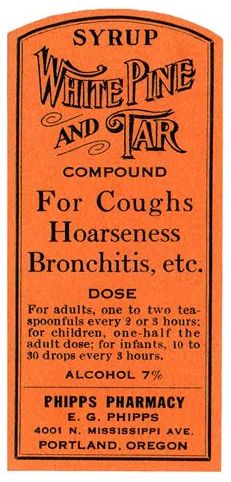

Creosote

Usually when you think of creosote you think of a wood preservative, like the type used on telephone poles. Creosote is distilled from wood tar—especially white pine or beechwood. A Civil War surgeon, however, would use it for a variety of ills, administering it both internally and externally. Creosote was used on wounds and ulcers and could also be applied to the throat to sooth soreness. Taken orally as a liquid, it was used to treat infected sinuses, diabetes, epilepsy, hysteria, neuralgia, tuberculosis of the lungs, and to clear out mucus caused by “catarrh” (the common cold).[2] Beechwood creosote especially was considered a good laxative and cough suppressant, and also was used for pneumonia and leprosy. The major chemicals in beechwood creosote are phenol, cresols, and guaiacol. Today the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry warns that taking these remedies may result in damage to the liver or kidneys.[3]

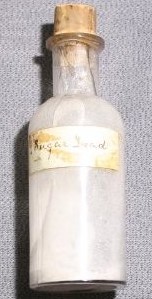

Lead Acetate

Today most people are aware of the harmful effects of exposure to lead, but Civil War surgeons often prescribed lead acetate, also known as sugar of lead. It was used both internally as a sedative, and externally as an astringent. When taken orally, lead acetate was used to promote sleep in “excitable cases,” as a cough suppressant, a spasm reducer in cases of tetanus or colic, and as a gargle for throat lesions.[4] Combined with opium to make a lotion, it could be used topically as a treatment for skin infections. In one recorded case, a soldier with “typhoid dysentery” was treated with lead acetate pills, opium pills, mercury pills, and an opiate enema. Needless to say, he died within 24 hours.[5]

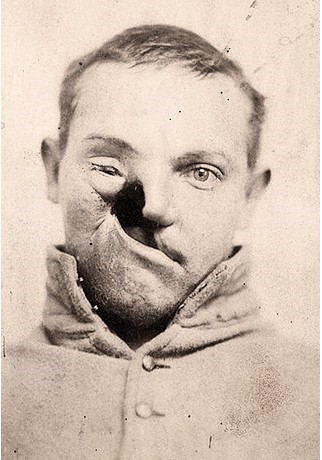

Mercury-Based Drugs

As early as 900 A.D., doctors were using mercury in various forms to treat their patients. It was used both externally and internally as a cathartic and laxative and to treat liver disease, typhoid fever, diarrhea, dysentery, and various skin diseases. It could be given as a liquid (“calomel”), an ointment, or in a pill form known as “blue mass” or “blue pills”—a mixture of mercury, licorice, rose leaves, and honey.[6] William H. Taylor, assistant surgeon for the Confederate army, wrote after the war that he had simplified sick call to one question: “How are your bowels? If they were open I administered a plug of opium; if they were shut I gave them a plug of blue mass.”[7] During the Civil War, mercury was perhaps the most well-known treatment for venereal disease. A common saying among the soldiers was that “one night with Venus brings a lifetime with Mercury.” Today we know that mercury is corrosive to the skin, eyes, and gastrointestinal tract, and may induce kidney failure if ingested. It can also cause damage to the central nervous system.

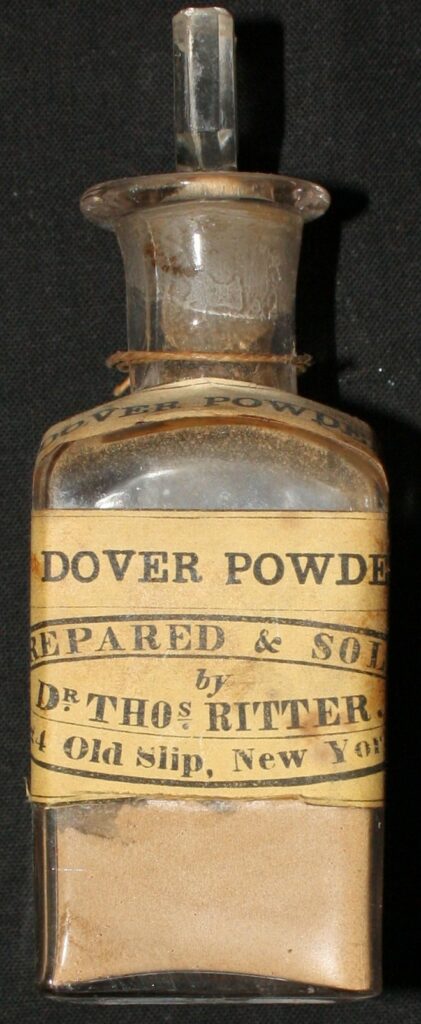

Opium

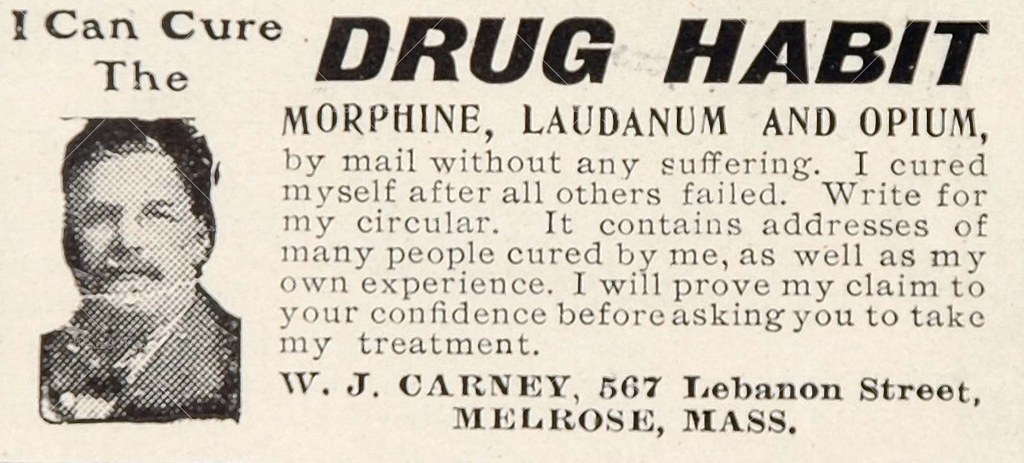

While opium was considered to be a very effective drug, Civil War surgeons did not understand that it could result in addiction, which was extremely detrimental to their patients. Opium is derived from the opium poppy and was most commonly used to relieve pain. It was also prescribed for diarrhea, gallstones, tetanus, typhoid fever, pneumonia, and many other diseases. It could be administered in the form of a powder, pills, or liquid. The most common liquid form was laudanum, and the powder form was most often Dover’s powder, which was a mixture of opium and ipecac. The medical records from the U.S. Army showed ten million opium pills were distributed to soldiers during the Civil War, and three million ounces of laudanum and powder.[8]

Veterans who had been treated with opium for wounds or disease would often become addicts, and this resulted in an opioid epidemic in the years following the war. It was not until the 1890s that this problem would be addressed by restricting the use and prescription of opiates and the opening of clinics to treat addicts.

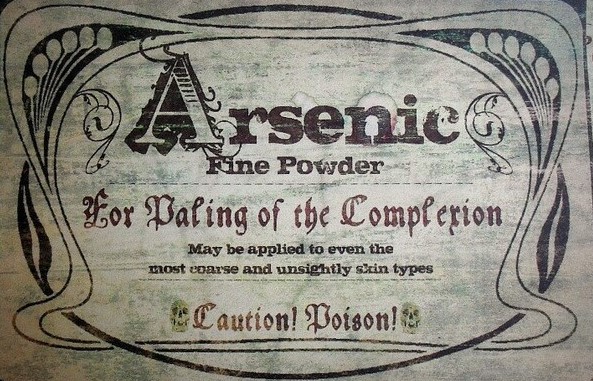

Arsenic

Several different forms of arsenic were used for medicinal purposes starting in the 17th century. It was most commonly used to treat syphilis but was also added to medications to treat a variety of skin diseases, including psoriasis. One of the most prevalent forms was Fowler’s Solution, a liquid form of arsenic trioxide developed in 1786 by Thomas Fowler in England. By 1865 doctors were prescribing the solution for the treatment of leukemia, malaria, and syphilis. Arsenic is a deadly poison, and medical professionals had to use extreme care not to overdose their patients. In small doses, doctors found that it worked very well as a stimulant, and this was prescribed from the mid-18th to 19th centuries. [9]

Given all of these “bad medicines” it seems a miracle that any patients survived. However, “good medicines” such as quinine (still in use today to fight malaria) were also used. And to their credit, medical professionals eventually did understand the detrimental and often deadly effects of the drugs they were prescribing. Indeed, in 1863 Surgeon General William Hammond made it a personal mission to lessen the use of mercury in medicines. As a result of his crusade, Hammond was fired, but he eventually was proven correct. While Civil War surgeons were often innovative in their treatments, we can also be thankful that they learned from their mistakes.

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Director of Communications at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield. She is also an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises.

Sources

[1]Taylor, “Opiates During the American Civil War: Not Just for Soldiers,” American Civil War Forum, 2017

[2] Hamilton, Andrew and the NMCWM Press, Diseases and Drugs of the Civil War, 2009

[3] https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/PHS/PHS.aspx?phsid=64&toxid=18

[4] Hamilton, Andrew and the NMCWM Press, Diseases and Drugs of the Civil War, 2009

[5] Ibid.

[6] Hamilton, Andrew and the NMCWM Press, Diseases and Drugs of the Civil War, 2009

[7] Street, James. “Under the Influence: Marching Through the Opium Fog,” Civil War Times, May 1988

[8] Hamilton, Andrew and the NMCWM Press, Diseases and Drugs of the Civil War, 2009

[9] Parascandola, John. King of Poisons: A History of Arsenic. pp. 145–172.