Table of Contents

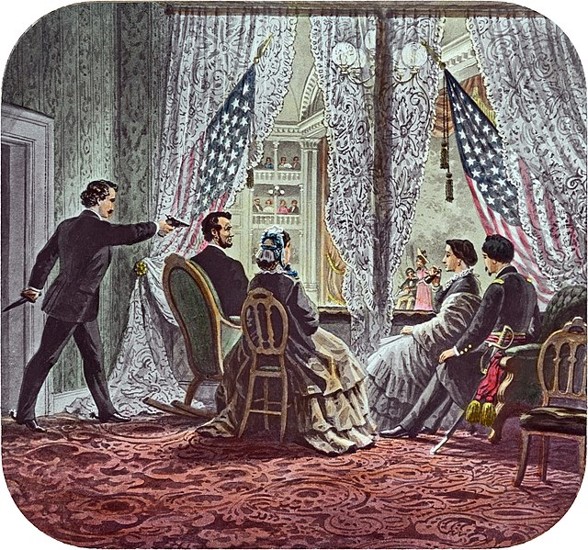

“Not accustomed to the manners of good society, eh? Well I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old woman; you damned old sockdologizing man-trap!” Harry Hawk, the lead actor in the play Our American Cousin, delivered the punchline to the funniest joke of the play. As the crowd went up in a roar of laughter, John Wilkes Booth slipped into President Abraham Lincoln’s box and shot him in the back of the head with a Derringer pistol. After a brief struggle with Major Henry Rathbone, Booth jumped from the balcony to the stage, breaking his leg in the process, and making his escape as he shouted “Sic Semper Tyrannus! The South is avenged.” The President was quickly taken across the street to the Petersen House where doctors made multiple attempts to treat his fatal wound.[1] Nine hours later, the next morning at 7:22 AM, President Lincoln was pronounced dead.

Medicine had come a long way towards the end of the Civil War. George Washington, our first President elected after the ratification of the US Constitution, died in 1799 due to medical procedures that had almost entirely been phased out or discontinued by 1865. After being exposed to the cold and rain for an extended period of time, Washington came down with pneumonia. The doctors seeing to him employed bloodletting (32oz were taken) and blistering of the extremities. They also administered doses of calomel (mercury), vapors of vinegar and water, and multiple doses of emetic tartar “with no other effect than a copious discharge from the bowels.”[2] Pneumonia was already a fatal disease in 1799, but the treatments the doctors used on President Washington were what really killed him. While mercury-based drugs such as calomel and emetic tartar were still in the surgeon’s kit throughout the Civil War, bloodletting, blistering, and other methods of heroic medicine were seldom performed.

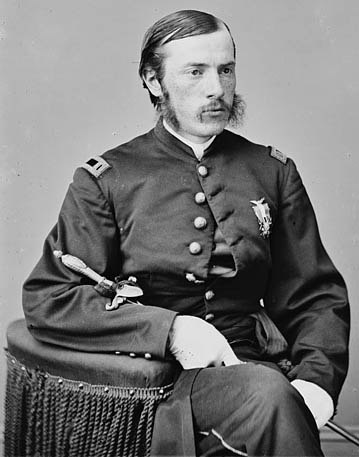

Dr. Charles Leale, who was on hand the night of Lincoln’s assassination, was a recent medical school graduate when he began his service in the Army at the Wounded Commissioned Officer’s Ward at Armory Square’s General Hospital in Washington, DC.[3] Dr. Leale, reportedly went into DC on the evening of April 14 to catch a glimpse of the President and General Ulysses Grant; as it turned out, General Grant was not able to join the Lincoln family, and Major Henry Rathbone took his seat. The play began after Lincoln and his party entered the box and all was going well until Dr. Leale and the rest of the audience heard a gunshot and a man, John Wilkes Booth, leaped from the Presidential box, brandishing a bloody dagger before his spur became caught on one of the American flags hanging from the box.

Someone called for a doctor and Dr. Leale jumped into action, becoming the first doctor on scene to examine the wounded President. Major Rathbone, in an attempt to stop Booth, caught the blade of his dagger which lacerated his forearm. After hearing Mrs. Lincoln’s calls for assistance, Dr. Leale saw to the President and began his examination of the wounds.[4] Dr. Leale, with the help of others, moved President Lincoln to the recumbent position (laying on his back with the lower extremities flexed and rotated outward) where he began to examine him for a stab wound as Dr. Leale only saw the knife and not the pistol. However, there was no evidence of a knife wound of any sort and that is when Dr. Leale discovered evidence of a brain injury when examining Lincoln’s pupils. Modern doctors still use this method to examine for any sort of brain injury.

The ball from the pistol wielded by Booth missed an area of the brain that would have resulted in instant death by about two inches, according to Dr. Leale. Instead, the ball hit the thickest part of the skull in the occipital bone. Dr. Leale would later say, “the history of surgery fails to record a recovery from such a fearful wound and I have never seen or heard of any other person with such a wound, and injury to the sinus of the brain and to the brain itself, who lived even for an hour.”[5] Dr. Leale did inadvertently relieve some of the pressure caused by the swelling of the brain when he probed the injury with his finger. In doing so, he removed the clot that began to form and allowed for the free flow of blood to the brain thus reducing the swelling.

When the President did not revive from this procedure, Dr. Leale attempted to resuscitate him. There were two methods of resuscitation that were used in the 19th century; Dr. Marshall Hall’s Ready Method and Dr. Henry Silvester’s method. Both methods were almost nothing like modern CPR. However, in his attempt at resuscitation, Dr. Leale did attempt to perform mouth-to-mouth on the President:

During the intermissions I also with the strong thumb and fingers of my right hand by intermittent sliding pressure under and beneath the ribs, stimulated the apex of the heart, and resorted to several other physiological methods… I leaned forcibly forward directly over his body, thorax to thorax, face to face, and several times drew in a long breath, then forcibly breathed directly into his mouth and nostrils, which expanded his lungs and improved his respirations.[6]

By performing this procedure on the President, Dr. Leale was able to prevent instant death as Lincoln began to breathe on his own. However, despite this improvement, Dr. Leale still pronounced President Lincoln’s wound as mortal while in the Presidential box at Ford’s Theater. The decision was then made to do whatever was necessary for the President and his family in a more comfortable setting.

Dr. Leale made the decision to transport President Lincoln to the Petersen House across the street, as the six-block wagon ride to The White House along the bumpy stone roads of DC would have killed him.[7] Dr. Leale, accompanied by Drs. Charles S. Taft and Albert F. King, carried the President across the street. An unnamed captain requested orders from Dr. Leale who told him to clear a path across the street. The group made their way to the Petersen Boarding House and situated Lincoln on a bed in one of the rooms. However, the President and his 6’4” build were too tall for the bed “I had the President placed diagonally on the bed and called for extra pillows, and with them formed a gentle inclined plane on which to rest his head and shoulders.”[8] Once the President was situated, Dr. Leale continued with his examination in order to figure out if he could prolong Lincoln’s life.

While at the Petersen House, little was done to the President as there was not much to do. Dr. Leale describes sending messengers to notify the President’s family, his Cabinet, the Surgeon General at the time Dr. Joseph K. Barnes, the family physician, and Mrs. Lincoln’s pastor Rev. Dr. Phineas Gurley. In the meantime, Dr. Leale continued to clear clotted blood from the wound site in order to keep the swelling down. Dr. Leale and his team did notice that the President’s extremities were cold, so they situated bottles of hot water and hot blankets in between them and his torso while also putting sinapism (mustard powder) on his chest. Dr. Taft, one of those assisting since the beginning of this ordeal, came to Dr. Leale with brandy and water for the President. Dr. Leale reluctantly let Dr. Taft administer the brandy which caused a “laryngeal obstruction and unpleasant symptoms… but no lasting harm was done.”[9]

Sometime after the Surgeon General and his Assistant arrived, a hospital steward arrived with a Nelaton Probe, a device used by surgeons to probe wound sites for bullets and other foreign bodies. Dr. Leale was using his finger before getting the probe at around 2 A.M.[10] as was fairly common for surgeons at this time. When the doctors used the probe, they found debris in multiple locations along the projected bullet trajectory.

The probe touched something at two and a half inches and passed another several inches further before coming into contact with another foreign substance believed to be the ball (musket ball from the Derringer pistol shot by Booth). However, the tip of the probe when extracted did not have any of the indicating marks of the presence of lead, leading the doctors to propose that it was a piece of bone. The probe was inserted again, and it was met with resistance to an object this time believed to be the ball. The probe was again removed, and the wound was left alone except for the occasional clearing of clotted blood when the President’s breathing became labored.[11]

Shortly after, First Lady Mary Lincoln fainted and was escorted to a different room until the passing of President Lincoln. She wanted her son, Tad Lincoln, to be able to see his father before he passed, which the doctors in the room did not advise. For the remainder of their time in the Petersen House, the oldest of the Lincoln sons, Captain Robert Lincoln, stayed with his mother for comfort. Dr. Leale promised the First Lady that he would do all he could for the wounded President. As he had already done all he was able, Dr. Leale took the seat formerly occupied by her and held the hand of the President, only letting go once to speak with her again.[12]

Both Dr. Leale and Surgeon General Dr. Barnes would continuously check the pulse of the President; Dr. Leale checking the radial pulse while Dr. Barnes checked the carotid pulse. As time passed, both men began to feel the pulse weaken and see President Lincoln’s respiratory rate fall. At around 7:21 AM, Lincoln could not be observed breathing and about a minute later at 7:22 AM, the President’s pulse stopped, and he was pronounced dead.[13] While Lincoln’s cause of death was much different than that of George Washington over sixty years earlier, it shows how much medicine had evolved in that timeframe. Bloodletting and blistering were gone, and doctors were trained in medical schools instead of by apprenticeships that taught centuries-old methods. Medicine still would have a long way to go before some doctors could claim that they could have saved the life of Lincoln but the Civil War laid the important groundwork for modern medicine.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021. He is currently pursuing a Masters in American History from Gettysburg College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Sources

[1] “Lincoln’s Assassination.” Ford’s Theatre, n.d. https://www.fords.org/lincolns-assassination/.

[2] Warner, John Harley, and Janet Ann Tighe. Major Problems in the History of American Medicine and Public Health: Documents and Essays. Boston: Wadsworth, 2001. Pg 58

[3] Lively, Mathew W. “Charles A. Leale – the First Doctor to Aid Lincoln Following the Assassination.” Civil War Profiles, December 22, 2013. https://www.civilwarprofiles.com/charles-a-leale-the-first-doctor-to-aid-lincoln-following-the-assassination/.

[4] Leale, Charles Augustus. Lincoln’s Last Hours: Address Del. in Observance of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of President Abraham Lincoln. (New York), 1909. Pg 4

[5] Leale, Charles Augustus. Lincoln’s Last Hours: Address Del. in Observance of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of President Abraham Lincoln. (New York), 1909. Pg 5

[6] Leale, Charles Augustus. Lincoln’s Last Hours: Address Del. in Observance of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of President Abraham Lincoln. (New York), 1909. Pg 6

[7] “Lincoln’s Assassination.” Ford’s Theatre, n.d. https://www.fords.org/lincolns-assassination/.

[8] Leale, Charles Augustus. Lincoln’s Last Hours: Address Del. in Observance of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of President Abraham Lincoln. (New York), 1909. Pg 8

[9] Leale, Charles Augustus. Lincoln’s Last Hours: Address Del. in Observance of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of President Abraham Lincoln. (New York), 1909. Pg 9

[10] “‘His Wound Is Mortal; It Is Impossible for Him to Recover’ – the Final Hours of President Abraham Lincoln.” National Museum of Health and Medicine, n.d. https://www.medicalmuseum.mil/index.cfm?p=visit.exhibits.current.collection_that_teaches.lincoln.page_02.

[11] Leale, Charles Augustus. Lincoln’s Last Hours: Address Del. in Observance of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of President Abraham Lincoln. (New York), 1909. Pg 10

[12] Leale, Charles Augustus. Lincoln’s Last Hours: Address Del. in Observance of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of President Abraham Lincoln. (New York), 1909. Pg 11

[13] “‘His Wound Is Mortal; It Is Impossible for Him to Recover’ – the Final Hours of President Abraham Lincoln.” National Museum of Health and Medicine, n.d. https://www.medicalmuseum.mil/index.cfm?p=visit.exhibits.current.collection_that_teaches.lincoln.page_02.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.