Table of Contents

“Cleanse the one with a gnawing and putrid gangrene”

During the Civil War, a soldier’s biggest fear of death was not the battlefield, it was disease. Two-thirds of soldiers both Union and Confederate died of disease or infection by the end of the Civil War.[1] Of those who suffered battlefield wounds, gangrene or hospital gangrene was one of the deadliest infections at the start of the war. Gangrene still exists today; however, not as prevalent. One important thing to remember is that surgeons during the Civil War did not subscribe to germ theory. Many often did not disinfect their hands between patients, there was no sterilization of surgical instruments, and there was a misunderstanding about wound discharge that proved harmful to many soldiers. Surgeons would observe the yellowish pus coming from a wound as a good sign, as they believed it was “laudable pus” a pus that meant infection, but one that the patient would likely survive. During that time, infection was extremely common, and it was often a gamble if the patient would survive it.

Gangrene during the Civil War often occurred in the outer extremities, such as arms, legs, fingers, and toes. The infection was seen so often in these places due to a high rate of amputations. Amputations were common because of a new type of ammunition called the Minie Ball. The bullet was made of a softer lead, which caused it to splinter and shatter bone usually resulting in amputation. If following an amputation, the wound was found to be infected or gangrenous, the surgeon would often amputate higher to stave off the gangrene. However, early in the war there were few effective treatments for hospital gangrene and its 60% mortality rate.[2]

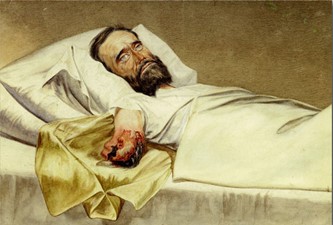

Hospital gangrene usually caused the patient’s skin to appear necrotic and smell extremely foul. The edges of the skin turned gray, and the skin would begin to decay rapidly.[3] It was extremely painful for the patient and often hard to look at. Many surgeons did not know the cause of hospital gangrene and there were continual efforts to combat the infection. One of the most popular attempts to eradicate the infection was airflow. During the Crimean War, it was recommended to give a patient that had hospital gangrene at least 1600 cubic feet (about half the volume of a one car garage) of clean air.[4] This was not always possible due to space and number of patients in the Civil War, but many hospitals encouraged airflow with as many windows as possible. However sometimes, if these windows were close to areas of bacteria, such as sewers or places of human excrement, cases of hospital gangrene increased.[5]

Some surgeons and medical staff had also started to discover that their own cleanliness procedures affected the patients. Doctors began the process of quarantining patients and in 1861 Dr. Frank Hamilton decided that every patient should have their own sponge, towels, and bedding and when their dressing was changed their dressings should be burned and not reused.[6] There are also isolated incidents throughout the Civil War of modern aseptic practices being used to promote safer medical practices.

One practice that is still used today is debridement. The doctor would use a sharp tool to cut off the infected tissue to curb the infection. However, early on this was done too late or could lead to more infection if not done properly. Toward the end of the war the combination of topical treatments and debridement boded well for a patient suffering from hospital gangrene.

Topical treatments were extremely popular in looking for a cure for hospital gangrene. Bandages with different muds, herbs, or plants were often applied to the gangrenous infection. Revolutionary treatments included nitric acid and bromine as a topical treatment. Nitric acid and similar treatments were extremely painful for the patient, and they often had to be anesthetized for the procedure.[7] One method involved the use of coffee and whiskey as a treatment for gangrene, which proved to be wholly ineffective. It was not until 1864 that the use of bromine became widespread, and this was thanks to the work of Middleton Goldsmith.

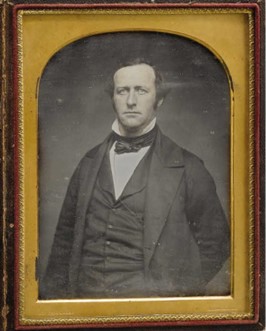

Dr. Middleton Goldsmith worked in the Louisville area as a Union Brigade-Surgeon. When his hospital was overrun by hospital gangrene, he decided to run tests to come closer to an effective treatment for the deadly ailment. He had originally thought that hospital gangrene, erysipelas, and pyaemia were all three connected and he wanted to find something to cure all three.[8] He began observing the patients lying in his hospital, and he observed that some doctors were using bromine in an aerosolized form, and these patients were more likely to survive hospital gangrene.[9] After he concluded that topical treatments like nitric acids were beneficial to eradicating the gangrene, he also concluded that nitric acid killed healthy tissue and was far too painful for the patient. Through testing Dr. Goldsmith was able to discover a method of inserting bromine into the gangrenous tissue along with debridement to bring the mortality rate from 46% throughout the Civil War to 3% in his patients in which he used bromine.

Dr. Goldsmith was not entirely sure how or why it worked, but it most definitely did. Of the 334 cases of hospital gangrene in Dr. Goldsmith’s hospital, 304 received bromine treatment, and of those 304, only 8 died following bromine treatment.[10] Goldsmith’s work was revolutionary, as it predated Joseph Lister’s germ theory, and was extremely successful in mitigating hospital gangrene. Gangrene reappeared in times of war after the Civil War, but never on the same scale as hospital gangrene. In World War II and the Korean War, cases of gangrene had an exceptionally low mortality rate due to the advent of in vivo penicillin. Hospital gangrene was extremely deadly for the soldiers of the Civil War and thanks to developments made by brilliant surgeons, the medical world gained a high level of understanding of the disease and hospital gangrene has been eradicated.

About the Author

Riley Clipson is the Intern this summer for the National Civil War Medicine Musuem. She is a current student at Gettysburg College with a double major in International Studies and German, with a minor in Public History.

Sources

Trombold, John M. “Gangrene Therapy and Antisepsis Before Lister: The Civil War Contributions of Middleton Goldsmith of Louisville.” The American Surgeon, vol. 77, no. 9, 2011, pp. 1138–1143, https://doi.org/10.1177/000313481107700924.

[2]Murray, Clinton K., et al. “History of Infections Associated with Combat-Related Injuries.” Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection & Critical Care, vol. 64, no. 3, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0b013e318163c40b.

[3] Schroeder-Lein, Glenna R. The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine. Taylor & Francis Group, 2008.

[4]Trombold, John M. “Gangrene Therapy and Antisepsis Before Lister: The Civil War Contributions of Middleton Goldsmith of Louisville.” The American Surgeon, vol. 77, no. 9, 2011, pp. 1138–1143, https://doi.org/10.1177/000313481107700924.

[5] Trombold, John M. “Gangrene Therapy and Antisepsis Before Lister: The Civil War Contributions of Middleton Goldsmith of Louisville.” The American Surgeon, vol. 77, no. 9, 2011, pp. 1139, https://doi.org/10.1177/000313481107700924.

[6]Trombold, John M., M.D. “Gangrene Therapy and Antisepsis before Lister: The Civil War Contributions of Middleton Goldsmith of Louisville.” The American Surgeon 77, no. 9 (09, 2011): 1139. http://ezpro.cc.gettysburg.edu:2048/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/gangrene-therapy-antisepsis-before-lister-civil/docview/888059590/se-2.

[7] Schroeder-Lein, Glenna R. The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine. Taylor & Francis Group, 2008.

[8]Trombold, John M. “Gangrene Therapy and Antisepsis Before Lister: The Civil War Contributions of Middleton Goldsmith of Louisville.” The American Surgeon, vol. 77, no. 9, 2011, pp. 1141, https://doi.org/10.1177/000313481107700924.

Trombold, John M. “Gangrene Therapy and Antisepsis Before Lister: The Civil War Contributions of Middleton Goldsmith of Louisville.” The American Surgeon, vol. 77, no. 9, 2011, pp. 1141, https://doi.org/10.1177/000313481107700924.

[10] Goldsmith, Middleton. Report on Hospital Gangrene, Erysipelas and Pyaemia. Bradley & Gilbert, 1863.