Table of Contents

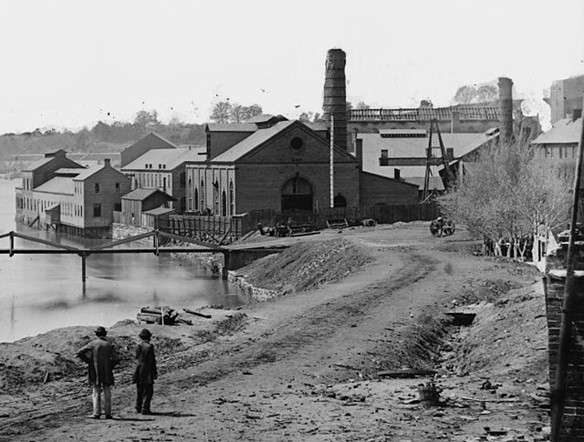

The state of Virginia was home to the capital of the Confederacy and became a central location for battles fought over the course of the Civil War. Armies, North and South, marching through cities, towns, and farmlands of Virginia, foraging their way through the countryside, devastated the agricultural crop. The sustained battles across the state destroyed farmland, the bodies of dead soldiers poisoning the earth and rivers which fed the crops. Virginia had been brutalized and the citizens on the home front were feeling the effects of the hardening of war. The 148th Pennsylvania Infantry records in their regimental history the difference between Maryland and Virginia in June of 1863, “the land here is very good and the country beautiful for miles around. The residences are fine and altogether it looks very much like home. The desolation of war has blighted Virginia and the difference is very marked between Virginia and Maryland.”[1] The destruction faced by Virginia and her citizens created harsh conditions for those living on the home front.

Both the state of Virginia and the Confederacy were struggling to adequately feed their soldiers as a result of the destruction of war and the Union blockade. In the capital of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, the workforce was made up of primarily middle or working-class women trying to assist the war effort or make some money to provide for their families. Rising taxes, increased pressure on farmers to produce, and inflation created an ever-growing disparity between the socioeconomic classes of wartime Richmond.[2] There was an exceedingly harsh winter between 1862 and 1863 where some “locals reported more than twenty measurable snow falls, with some storms dropping more than a foot of snow on the capital.”[3] This was followed by a reportedly warmer than usual early spring, and the roads became a mess and supplies to the city had trouble getting through. From the outside looking in, Richmond looked like a powder keg for potential civil unrest.

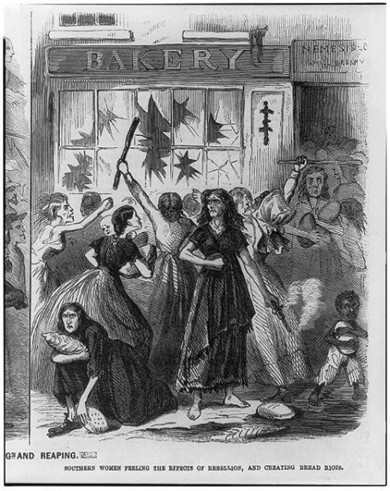

On April 1, 1863, about 3,000 working-class women of Richmond’s ordnance factories, along with the wives of men working in the Tredegar Iron Works, assembled at the monument to George Washington in Richmond. Thousands of women marched towards the mansion of Virginia Governor John Letcher in order to resolve the issues facing the city. Accounts of the exact events differ between accounts, especially when it came to the interactions between the rioters and Governor Letcher, and eventually, Confederate President Jefferson Davis himself. Some accounts describe interactions between all parties, while others describe the men in power as demanding the women to disperse or be fired upon by local militia and artillery pieces.[4] According to accounts, the thousands of women in the streets of Richmond dispersed fairly quickly fearing the men in charge of the militiamen would make true on their threats. One Richmond resident witnessed the events and would recall, “Governor Letcher sent the mayor to read the Riot Act, and as this had no effect on the crowd. The city battalion came up. The women fell back with frightened eyes, but did not obey the order to disperse.”[5]

Before the militiamen were ordered into the city to potentially fire upon the crowd, the women, many of them malnourished and emaciated, were chanting through the streets of Richmond. The women were breaking windows to government buildings and warehouses, looting from food storage facilities, and trying to get the message to government officials by any means necessary. Eventually, after the tensions cooled from the initial riots, a total of around sixty people were arrested and charged according to their demeanor and connection to the riot’s leadership.[6] However, the city heard the calls from its citizens and did release some of its food reserves to the starving “worthy poor” population of Richmond. Those in connection to the organization of the riots were deemed as “unworthy poor” and received little to no government assistance.[7]

As the war went on, food became scarcer for Confederate soldiers and citizens of seceded states. Richmond would not be the only city to have a “bread riot;” cities across the Confederacy experienced food shortages to the point where the people rose up and asked the government to act. The Richmond Bread Riot of 1863 and increasing food shortages also prompted Robert E Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to take some of the pressure off Virginia to give them time to recover from two years of a hardening war. Just three months after the Richmond Bread Riot, Lee was engaging General George Meade and the Army of the Potomac in Gettysburg, PA. While the bread riots were not the driving factor in influencing the Gettysburg campaign, it was one part of the decision to launch an invasion of the North.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021.

Sources

[1] Muffly, J. W. The Story of Our Regiment: A History of the 148th Pennsylvania Vols. Salem, MA: Higginson Book Co., 2008. Pg 170.

[2] Golding, Connie. “Civil War 150: ‘Bread! Bread!” The Confederate Bread Riots.” Ford’s Theatre, n.d. https://www.fords.org/blog/post/civil-war-150-bread-bread-the-confederate-bread-riots/.

[3] DeCredico, Mary. “Bread Riot, Richmond.” Encyclopedia Virginia, April 1, 1863. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/bread-riot-richmond/.

[4] DeCredico, Mary. “Bread Riot, Richmond.” Encyclopedia Virginia, April 1, 1863. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/bread-riot-richmond/.

[5] “Bread Riot in Richmond, 1863.” Eyewitness to History, n.d. http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/breadriot.htm.

[6] DeCredico, Mary. “Bread Riot, Richmond.” Encyclopedia Virginia, April 1, 1863. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/bread-riot-richmond/.

[7] DeCredico, Mary. “Bread Riot, Richmond.” Encyclopedia Virginia, April 1, 1863. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/bread-riot-richmond/.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.