Table of Contents

In honor of this year’s Women’s History Month, the National Museum of Civil War Medicine wants to acknowledge the contributions that Clara Barton made not only to the medical field, but to the Women’s Rights movement as well. At a time when women are still fighting to be paid wages equal to their male counterparts, we can refer to and take inspiration from Barton’s struggle to prove herself in a male-dominated environment over a century-and- a- half ago. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, men are paid $1,219 per week on average while women are paid $1,002.[1] Even those with advanced degrees show a discrepancy, with men making $1,998 and women making $1,546 on average.[2] In fact, women “must complete one additional degree in order to be paid the same wages as a man with less education.”[3]

During Clara Barton’s time, occupations were “more strongly linked to social identity than actual economic activity.”[4] Women’s main social identity was still expected to be that of wife, daughter, or mother. Still, many women financially contributed to their households by engaging in “industrial homework” such as taking in boarders or helping with agricultural production.[5] Despite their economic contributions, these jobs were seen as part of a woman’s role in running her household and were not considered to be “true” occupations.

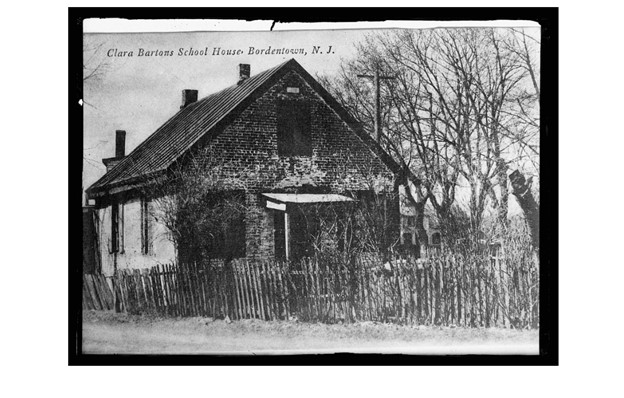

While women in 1860 certainly contributed to the economy much more than was recorded, Clara Barton continues to stand out because she overtly opposed and challenged occupational gender norms and wage gaps. Barton began her professional life as a teacher, opening a free school in Bordentown, New Jersey in 1852.[6] Between the 1820’s and 1830’s a movement was growing to improve public schools.[7] However, there were not enough men interested in teaching to fill all the positions for them.[8] Furthermore, male teachers were criticized as being too ambitious- many taught for only a few terms before pursuing more lucrative opportunities in other sectors. In their pursuit to make teaching its own distinct profession, schools turned to women- who were assumed to care little for material or professional rewards and prestige.[9] This meant that their labor was easily exploitable. In 1838, Massachusetts school returns reported an average monthly salary of $23.10 for men and only $6.49 for women, despite the fact that more women were employed as teachers than men.[10] Unfortunately, Clara Barton’s experience was no exception.

Barton’s school in New Jersey was undoubtedly a success, causing the residents of Bordentown to invest $4,000 in order to expand the school.[11] Because she had founded the school in the first place, Barton expected to be appointed principal. Unfortunately, a man was chosen to be principal of the institution instead and paid twice her salary. Clara stated, “I may sometimes be willing to teach for nothing, but if paid at all, I shall never do a man’s work for less than a man’s pay.”[12] She resigned and went on to look for other opportunities.

Barton’s next professional move was to the U.S. Patent Office- the “site of a radical experiment in equal pay for equal work.”[13] Barton along with other female clerks, were to work in the same spaces, do the same tasks, and receive the same salaries as male clerks. This short-lived experiment was the idea of Charles Mason who became the commissioner of patents in 1853. Although an advocate of emancipation, civil rights, and women’s rights, Mason may have also assumed that female clerks would be more loyal because they lacked other professional avenues. Regardless of his true motives, Barton felt comfortable in this new work environment, describing it as a “delightfully pleasant” situation in an 1854 letter to a friend.[14] Unfortunately, in 1855, Mason returned to Iowa and left Secretary of Interior Robert McClelland in charge. McClelland did not approve of female clerks and removed Barton and the other women from their roles. Despite McLelland’s efforts to eradicate the feminine presence in the workspace, Mason returned a few months later in 1855 and employed Barton once again, paying her a high salary and appointing her a “confidential clerk.”[15] She was the only woman allowed back into the male workplace and unfortunately was harassed because of it. According to her reports, male coworkers “blew smoke at her in the hallways and spat tobacco juice at her skirts.”[16] After DeWitt’s electoral defeat, Barton’s patronage network disappeared and by Christmas of 1857 she had been fired from the Patent Office.[17] Returning to Massachusetts in search of government clerical work, Barton was told there was “no room for ladies.” Fortunately, in 1860 as the Civil War approached, she was rehired as a copyist at the U.S. Patent Office and remained on the payroll throughout the Civil War by hiring a substitute to fill in for her as she ventured to the front lines bringing supplies and nursing the wounded.[18]

Clara Barton’s perseverance to be of service and prove that she belonged within male-dominated occupational fields should be an inspiration to all women who are still battling to do the same thing albeit over a century-and-a-half later. We can honor her legacy and continue her fight by advocating for women’s rights, equal pay, and female leadership.

About the Author

Elizabeth Eisenstark is the research and collections assistant at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. She received a BA in the History of Art and Visual Culture from the University of California Santa Cruz and is currently pursuing a post-bacc in Anthropology with a focus on Archaeology from Oregon State University.

Sources

Arlington Public Library, 4 Dec. 2023, library.arlingtonva.us/2020/03/19/angel-of-the-battlefield-humanitarian-clara-barton/.

“Autobiography, Speeches, Poetry, and Other Writings.” By the People, crowd.loc.gov/campaigns/clara-barton-angel-of-the-battlefield/autobiography-speeches-poetry-and-other-writings/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Chiswick, Barry R., and RaeAnn Halenda Robinson. “Women at Work in the United States since 1860: An Analysis of Unreported Family Workers.” Explorations in Economic History, Academic Press, 8 June 2021, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014498321000243.

Chun-Hoon, Wendy. “5 Fast Facts: The Gender Wage Gap.” DOL Blog, 14 Mar. 2023, blog.dol.gov/2023/03/14/5-fast-facts-the-gender-wage-gap#:~:text=Stats.,for%20Black%20and%20Hispanic%20women.

“Clara Barton (the Angel of the Battlefield).” eHistory, ehistory.osu.edu/biographies/clara-barton-angel-battlefield. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Melder, Keith E. “Woman’s High Calling: The Teaching Profession in America, 1830-1860.” American Studies, journals.ku.edu/amsj/article/view/2397. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Swanson, Kara W. “Rubbing elbows and blowing smoke: Gender, class, and science in the nineteenth-Century patent office.” Isis, vol. 108, no. 1, 2017, pp. 40–61, https://doi.org/10.1086/691396.

Understanding the Gender Wage Gap – U.S. Department of Labor, www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WB/equalpay/WB_issuebrief-undstg-wage-gap-v1.pdf. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Notes

[1] Chun-Hoon, Wendy. “5 Fast Facts: The Gender Wage Gap.” DOL Blog, 14 Mar. 2023, blog.dol.gov/2023/03/14/5-fast-facts-the-gender-wage-gap.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Arlington Public Library, 4 Dec. 2023, library.arlingtonva.us/2020/03/19/angel-of-the-battlefield-humanitarian-clara-barton/.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 22.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Swanson, Kara W. “Rubbing elbows and blowing smoke: Gender, class, and science in the nineteenth-Century patent office.” Isis, vol. 108, no. 1, 2017, pp. 40–61, https://doi.org/10.1086/691396.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.