Table of Contents

Sarah Handley-Cousins

The harrowing story of Aurelia Johnson, the contraband slave woman working at the Mansion House Hospital, took yet another tragic turn in the most recent episode of PBS’s Mercy Street. Johnson, who suspected herself to be pregnant after being raped by menacing hospital steward Silas Bullen, first attempted to induce an abortion by using an herbal remedy. When that failed, she tried again, this time using a metal rod.

Aurelia’s first attempt to end her pregnancy was to take a tincture of pennyroyal, given to her by Belinda Gibson, house servant to the Green family. Pennyroyal has been used as an abortifacient since at least the time of the Greeks. It is referenced in Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, in which a beautiful young woman is described as being “trimmed and spruced with pennyroyal,” a reference to her use of the herb as a form of birth control. This was a joke, meaning that the young woman was all the more appealing because there would be no risk of an unintended pregnancy. The fact that an abortifacient could be used in a laugh line indicates the place abortion held in Greek society. In fact, pennyroyal, along with other herbs like rue, tansy, and other herbs, were commonly used for contraceptive purposes without taboo until well into the nineteenth century.[1]

For that matter, abortion itself was a fairly common and uncontroversial issue, in the United States and elsewhere, until the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Nineteenth century medicine placed emphasis upon maintaining a balance between bodily fluids (known as the humoral theory of medicine). When a woman’s menses stopped, whether because of a pregnancy or another reason, it was often interpreted as an unhealthy imbalance of humors with needed to be addressed. Women attempted to ‘restore’ menstruation by taking herbal or medicinal remedies known as emmenagogues. This was not considered problematic. Fetuses were not recognized as human lives, but rather a “blockage” until quickening, or when a women first felt the fetus move, generally in the fourth or fifth month. After this point, abortion would be taboo. What women did before this point was considered strictly the purview of women. As historian Leslie Reagan notes, “this age-old idea underpinned the practice of abortion in America….The legal acceptance of induced miscarriages before quickening tacitly assumed that women had a basic right to bodily integrity.”[2]

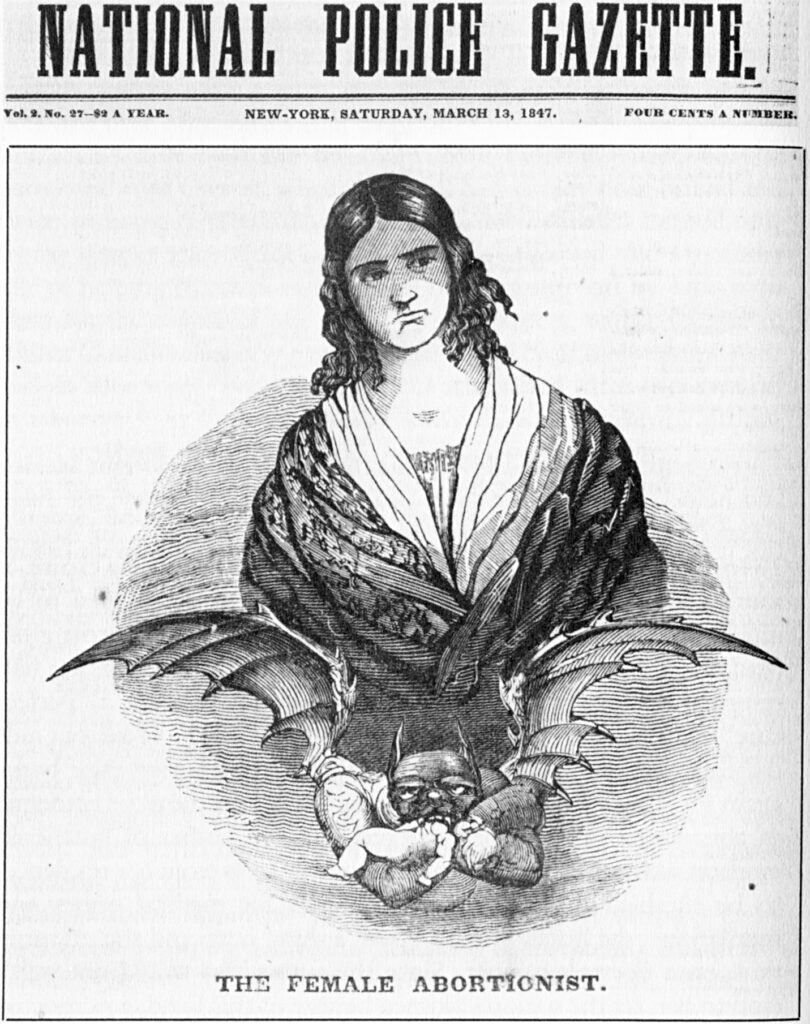

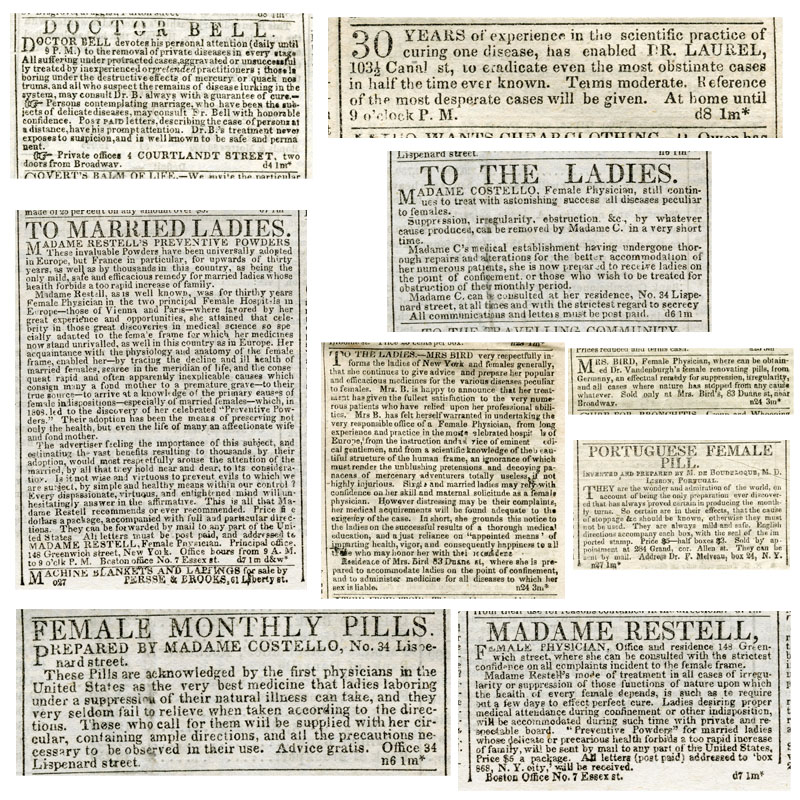

In the 1820s and 1830s, states began to outlaw the sales of abortifacients, making it more difficult for women to procure these “poisons,” but women still grew and concocted their own herbal remedies. In 1857, the American Medical Association began to advocate against abortion, declaring pregnancy the domain of physicians and rejecting women’s own bodily experience – thereby dismissing the experience of quickening as a turning point.[3] Instead, abortion at any point during a pregnancy became immoral, and increasingly, illegal. Illinois, for example, outlawed abortion at any stage of pregnancy, unless mandated by a doctor, in 1867.

Herbal remedies to induce miscarriage were equally well known to enslaved women. Slaves often grew herbs and mixed their own medicine, derisively referred to as “negro remedies” by Southern whites. A common concern among slave-owners (who, as I mentioned in my last post, stood to gain from their slaves’ pregnancies) was that slave women were using cotton root as an abortifacient. Historian Sharla Fett writes that white doctors worried that enslaved women were using those old emmenagogues pennyroyal, tansy and rue to end pregnancies. Just as with white women, doctors were eager to control the use of slaves’ herbal remedies, particularly those used to regulate menstruation.[4]

On Mercy Street, Dr. Foster estimates that Aurelia was very early in her pregnancy – perhaps, he states, only 5 or 6 weeks. While her desperation is certainly understandable, the dramatics with which her desire to end her pregnancy result in don’t seem necessary. Women regulated their menstruation for centuries, and in many cases, ended pregnancies without drama or incident. There is no doubt that there are stories of Aurelias throughout the history of the Old South, women victimized, hurt, and desperate – but there is also no doubt that there were many women who calmly chose to restore their menses, viewing it as women’s unique prerogative to control over their own bodies.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Sarah Handley-Cousins is a historian, teacher, and writer living in Buffalo, NY. She received a PhD in history from State University at New York at Buffalo in 2016. Her scholarly interests include medicine, gender, disability, and war studies.

She is also an editor at Nursing Clio and producer of The History Buffs Podcast.

[1] John M. Riddle, Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 46-47.

[2] Leslie Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and law in the United States, 1867-1973 (Berkley: University of California Press, 1997), 8-14.

[3] Reagan, When Abortion was a Crime, 10-11.

[4] Sharla Fett, Working Cures: Healing, Health and Power on Southern Slave Plantations (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 65.