Table of Contents

When we think of Civil War medicine, we often think of gore, like amputated limbs and bloody gunshot wounds. But these traumatic injuries did not make up the majority of a Civil War surgeon’s daily work. Instead, it was the camp diseases like dysentery and typhoid, infectious disease like smallpox, and – as we saw in this week’s episode of Mercy Street – venereal diseases.

Americans of the Civil War era were no prudes. While sex was certainly not a topic for polite conversation or reputation-minded members of the middle class, people still had complex desires. Historians John D’Emilio and Estelle Friedman, in their landmark history Intimate Matters, present the letters and diaries of many nineteenth century Americans, who wrote frankly about their sexual activity.[1] For the young, single men (and not a small number of wayward married ones) filling the ranks, life in the army provided them with new freedoms to seek out sex, generally with prostitutes.

During the antebellum, the middle class impulse toward reform moved many Americans to attack prostitution as a social evil. Early women’s rights activists looked at prostitution as evidence of that men’s sexual passions lead to ‘ruined’ women, while health reformers suggested that extra-marital and non-procreative sex sapped men’s vital energies. But this moralizing did little to stop women from seeking the world’s oldest profession, nor did it keep soldiers from visiting these ‘public women,’ particularly during the economic and social upheaval of the war years.

Fancy women, as Chief Surgeon Summers calls them, gathered wherever soldier-clients could be found, particularly cities like Alexandria or military camps.[2] Soldiers were away from the protective influence of families, and husbands were away from the loving embraces of their wives, for months, if not years, at a time. This could prove difficult for even the most loyal of husbands. For example, Samuel Cormany, though otherwise happily married, committed adultery against his wife Rachel while serving in the 16th Pennsylvania Infantry. When he returned home in 1865, he confessed his indiscretion to Rachel, expressing the “very worst features of my shortcomings and lapses.”[3]

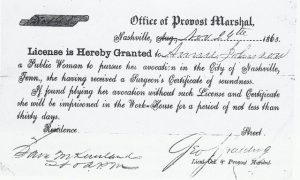

A natural result of paid (and largely unprotected) sex during the Civil War was venereal disease, specifically gonorrhea and syphilis. Confederate soldier J. M. Jordan, for example, wrote home to his wife in 1864 that though health in his regiment was good, they were dealing with a certain kind of disease: “I feel a delicacy in spelling them out to you as you are a female person but however I reckon you can’t blush little things these times. It is the Pocks [syphilis] and the Clap [gonorrhea].”[4] Physicians and nurses – like Nurse Phinney – understood this as a public health crisis rather than a moral one. In an attempt to stop the spread of syphilis through the ranks of the Union army, officials in Tennessee began an initiative that would evaluate the health of prostitutes, and provide those deemed free from disease with a license to ply their trade. (The women found to have venereal diseases were warehoused in hospitals without their consent – their clients, on the other hand, suffered no punishment.) Similar measures were also taken in Memphis. While this bore the appearance of profiting both working women and soldiers, it privileged the health of the fighting force over the bodily autonomy of prostitutes.[5]

So while it’s not quite as dramatic as an amputation, Nurse Phinney’s desire to provide health care for prostitutes and her concern for the larger public health in Alexandria not only reflects a more mundane aspect of Civil War medicine, but of warfare since time immemorial.

About the Author

Sarah Handley-Cousins is a PhD candidate in history at the State University of New York at Buffalo. Her scholarly interests include medicine, gender, disability, and war studies. She is also an editor at Nursing Clio and producer of The History Buffs Podcast.

Footnotes

[1] John D’Emilio and Estelle B. Freedman, Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, 1997, 2012), 55-139.

[2] This was a concern for all armies and navies, not just those in the United States! Syphilis alone had plagued European armies and navies since at least 1500. See James R. Arnold, Health Under Fire: Medical During America’s Wars (Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 2015), 23-24.

[3] John C. Mohr, ed., The Cormany Diaries: A Northern Family in the Civil War (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1982), 581.

[4] Thomas P. Lowery, The Story the Soldiers Wouldn’t Tell: Sex in the Civil War (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 1994), 30.

[5] D’Emilio and Freedman, Intimate Matters, 184-185.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.