Table of Contents

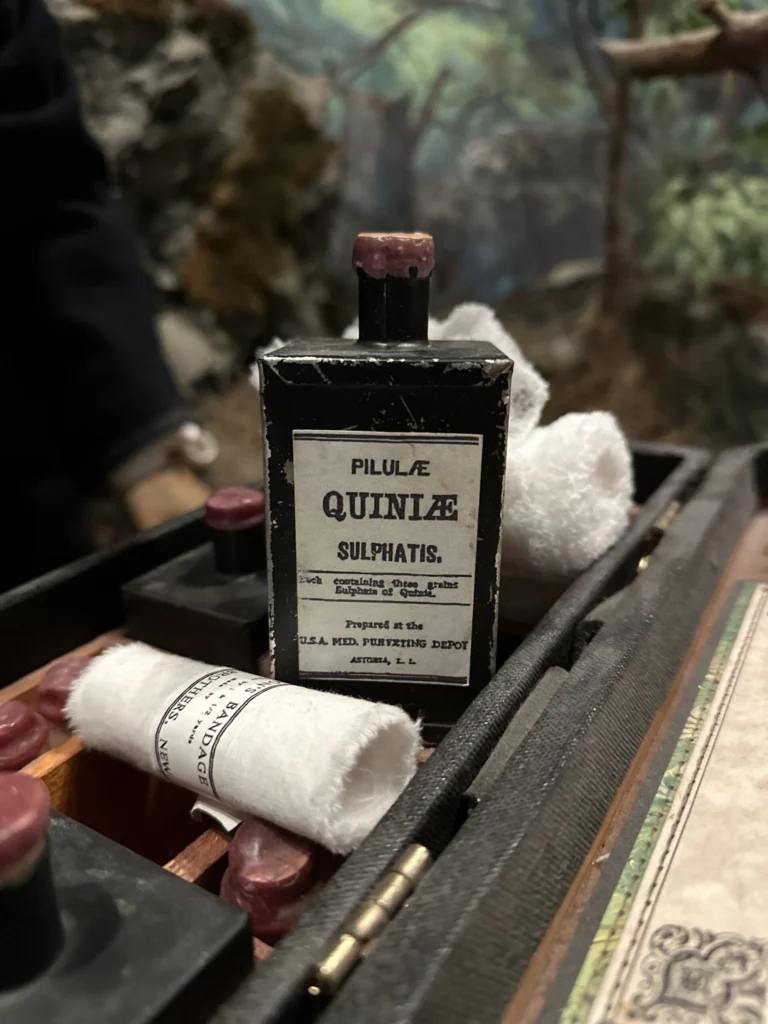

Soldiers in the Civil War were exposed to many diseases—in fact, two-thirds of all the deaths in the war were from disease and not from wounds. Unfortunately, the cause of disease and how to prevent its spread was unknown to Civil War surgeons. Many ascribed to the theory of “miasma” or bad air causing the outbreaks of malaria that occurred in camps located near swamps or other mosquito-infested areas. It wasn’t until 1880 that the cause was found to be parasites transmitted by mosquito bites. What the surgeons of the day did know, however, was the most effective treatment for the disease was quinine.

The first use of quinine to treat fevers occurred in the 16th century. Jesuits had observed the natives of Peru making a liquid from water and the bark of the cinchona tree, which would act as a muscle-relaxant to alleviate the shivering suffered by those infected with malaria. “Jesuit’s bark” was brought back to Europe and used successfully as a treatment. It gained in popularity when it was used to cure King Charles II of England of malaria in the late 17th century. The active ingredient in the bark was eventually named quinine.

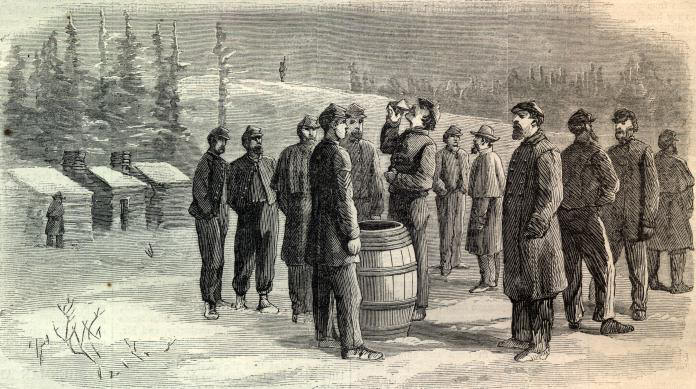

During the Civil War, northern soldiers in the southern states suffered the most from malarial outbreaks. A volunteer soldier from New York stationed near Charleston, South Carolina wrote “our worst picket duty is on the borders of the swamp. The myriads of stout ringtailed mosquitoes rush upon the detail the moment it arrives and jabs their bills in the chuck up to the head… Sleep is of course impossible with such a ravenous hoard of bloodsuckers…”[1]

Civil War surgeons used quinine as an effective treatment and preventative medicine against malaria. The Union alone provided a total of “19 tons of the powdered bark and 9 ½ tons of quinine sulfate”[2] to surgeons and hospitals. The drug was often given as a preventative, for example, during the Vicksburg campaign the Surgeon General ordered all soldiers to take quinine daily “because ‘intermittent fevers’ were so common.” [3] Quinine was given to the troops so often that they improvised words to the bugle call announcing sick call: “Dr. Jones says, Dr. Jones says: Come and get your quin, quin, quin, quinine. Come and get your quinine, Q-u-i-n-i-n-e!”[4] Because quinine is so bitter, surgeons often had a hard time getting the soldiers to take their ration but found that mixing it with whiskey often did the trick.

Soldiers in the Confederate army, while often used to the southern climate, would still fall victim to malaria. Due to the Union blockade of southern ports, however, Confederate surgeons had more difficulty getting medical supplies, including quinine. Dogwood, Georgia poplar, and willow barks were mixed with whiskey and observed to be an adequate substitute. Another such method of treating malaria that became more common in the Southern army was the external application of turpentine developed by Dr. Josiah Clark Nott in the 1850s. As the Confederacy began to run out of quinine, surgeons turned to this method and “the use of turpentine along with quinine proved to be effective and also reduced the amount of quinine to be administered.”[5] In 1864, Private D. D. Stubs of the 21st South Carolina came down with a fever and as there was no quinine available, doctors administered turpentine over the course of two days. He was able to make a full recovery.[6]

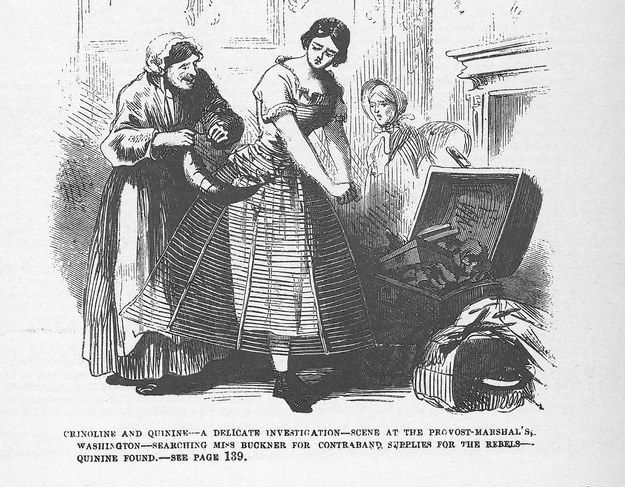

In addition to finding substitutes for quinine, Confederates also attempted to smuggle the medicine through the Union lines. According to one source, the daughter of the U.S. Postmaster General was discovered to have had sewn quinine packets into her dress while another was found with over $10,000 worth of quinine in a dead mule.[7] It is safe to say that quinine was one of the most valuable drugs on the market during the Civil War.

Today there are synthetic drugs that are often used instead of quinine, and it is difficult to find it over the counter. One source for quinine that you might not be aware of is tonic water. There is a small amount present that gives the drink its distinctive bitter taste. The use of quinine during the Civil War is one of the rare success stories of 19th century medicine—it truly was a “miracle drug.”

Sources

[1] Miller, Gary L. “Historical Natural History: Insects and the Civil War.” American Entomologist, 1997, 227–34. Pg 233

[2] National Museum of Civil War Medicine, Malaria, Wall Panel.

[3] Bollet, Alfred J. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson: Galen Press, 2002. Pg. 236-7.

[4] Hicks, Robert D. “’The Popular Dose with Doctors’: Quinine and the American Civil War,” Science History Institute online, December 7, 2013.

[5] Cunningham, Horace Herndon. Doctors in Gray: The Confederate Medical Service. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993. Pg 193

[6] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Washington: G.P.O., 1883. Vol. 1, Part 3. Pg 186

[7] Miller, Gary L. “Historical Natural History: Insects and the Civil War.” American Entomologist, 1997, 227–34. Pg 233

About the Author

Tracey McIntire earned her BA in English at Rivier College in Nashua, NH. She is Lead Educator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, site manager of the Pry House Field Hospital Museum, and an interpretive volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield. She is also an active Civil War living historian, where she portrays a woman soldier in various guises.

Author’s note: Many thanks to Michael Mahr for his initial research on this topic

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.