Table of Contents

Silas Weir Mitchell was a Philadelphia native who was born the son of a prominent physician and seemed destined to become a doctor. Born with a silver spoon in his mouth, Silas was the rare combination of someone born rich but was also talented and intellectually curious. He graduate from the University of Pennsylvania and Jefferson Medical College, and like many rich sons of doctors he studied in Paris for a year, which then was the epicenter of medical innovation.

When the guns of Charleston Harbor fired on Fort Sumter, launching the Civil War, Silas was less patriotic than many northerners. Perhaps this was because in 1860 Philadelphia was a very “southern” northern city. Philadelphia merchants had benefited handsomely from slavery, and were, on the whole, unfriendly to abolitionism. Moreover, a third of students at the University of Pennsylvania and Jefferson Medical College (Mitchell attended both) were from the South. “I am more of a democrat than a republican not enough of either to please either,” Mitchell wrote his sister in July 1863.[1] “For my part I think all sides are in some,” Mitchell wrote to his sister a month later. “I have sympathy with something of all. Entire sympathy with none,” he wrote.[2]

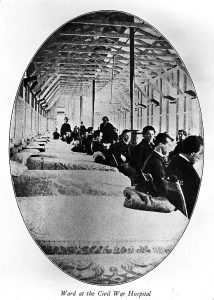

Weir, as his friends called him, was employed as a contract surgeon for the Union Army, and he began his first hospital service at an old armory building at 16th and Filbert Street in Philadelphia.[3] While he was working at the hospital on 16th and Filbert, Mitchell began to “take interest in cases of nervous diseases.” At the time, Mitchell remembered, nobody at the hospital desired to keep such cases because they were “so little understood” and “so unsatisfactory in their results.”[4] Weir was able to convince the new Surgeon General William Hammond to set aside a larger ward, devoted solely to the treatment and study of “neural maladies.” His tiny ward quickly overflowed, and a building known as Moyamensing Hall on Christian Street was opened. This also proved too small, so another, larger estate was procured.[5] Turner’s Lane was born. Working under a regular surgeon, Mitchell was joined by Dr. William W. Keen and Dr. George Morehouse at Turner’s Lane. They focused exclusively on nerve injuries among soldiers, working as a team.

Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London

The team examined and treated various forms of nerve damage, resulting from all kinds of injuries including gunshots, artillery shells, sabre swipes, falls and accidents. Nerve damaged soldiers, who had previously bounced around hospitals like hot potatoes, flooded their ward. One such soldier was a seventeen-year-old Pennsylvania native named David Schively. Schively, a private in the 114th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, had been wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg. During the second day of fighting, Schively rose up to fire his musket when an enemy ball smashed through his shoulder. To make things worse he was also shot in the face as he left the field, leaving him blind in his right eye.[6] He survived but soon began to suffer with a “burning pain in the palm and fingers” of his right hand.[7] By December 1863, the pain was so intense that the only remedy that brought Schively any relief was to keep both hands “covered with loose cotton gloves, which he wets at brief intervals.”[8] The pain had made him so “nervous and hysterical” that his “relatives supposed him to be partially insane.”[9]

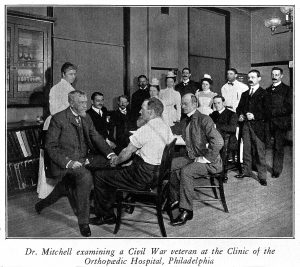

These were the injuries that interested the Turner’s Lane team; injuries to nerve centers, to the sympathetic nerve, and to nerve trunks or branches. They were also interested in changes to the muscles, including paralysis, and loss of tone and firmness. Mitchell achieved a number of groundbreaking discoveries while treating wounded Civil War soldiers. He and his team were one of the first to demonstrate the use of electricity as a form of treatment.[10] Mitchell would use electricity to stimulate the nerves and muscles, and to see whether neural connections could be remade, and if muscles could recover. Their work on reflex paralysis due to indirect lesion of the nerve substance, was considered, as Dr. Shauna Devine writes “their greatest contribution to the field.”[11] They also experimented with painkilling drugs such as morphia and atrophia, concluding that morphia was the most effective drug for relieving pain. Finally, Mitchell, Morehouse and Keen published a wartime publication Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of the Nerves, which was based on their notes and spelled out how to diagnose and treat nervous wounds.[12]

As Dr. Devine argues, Mitchell became one of the first specialists in American medicine, and is known as the father of neurology. While at Turner’s Lane, Mitchell came up with new treatments for nerve damaged men. He prescribed rest, along with massage and overfeeding. His time during the Civil War gave birth to his famous, or infamous, “Rest Cure.”

Courtesy of the Wellcome Library

After the war, Mitchell began a lucrative practice treating cases of middle class white women suffering from depression or anxiety. His Rest Cure, a combination of isolation, rest, massage and overfeeding, allegedly helped some women, but also nearly drove others insane. Part of what made the Rest Cure infamous was that Mitchell urged his female patients not to pursue an education or a career, and to embrace their domestic destiny. Several of his middle class white female patients were highly educated and extremely ambitious, and this prescription was a virtual death sentence for many. One of those women who came to despise the Rest Cure was Charlotte Perkins Gilman. A patient of Mitchell’s, he prescribed the Rest Cure along with an admonition to drop her creative writing endeavors. By her own admission, Mitchell’s prescriptions nearly drove her mad, until she finally rejected his advice and began to write again. The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte was partly based on her experience with Mitchell’s Rest Cure. Virginia Woolf and Jane Addams were also patients of Mitchell alcolytes, and ultimately rejected his treatment as well.

Footnotes

[1] Silas Weir Mitchell to Sister, 26 July 1863, Silas Weir Mitchell Papers, College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

[2] Silas Weir Mitchell to Sister, 10 August 1863, Silas Weir Mitchell Papers.

[3] This building was, also the setting for the beginning of Mitchell’s novel In War Time, which was based on his experiences. Nancy Cervetti, S. Weir Mitchell, 1829-1914: Philadelphia’s Literary Physician (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2012), 68.

[4] S. Weir Mitchell, M.D., Some Personal Recollections of the Civil War (Philadelphia: Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 1905), 5.

[5] Ibid., 5.

[6] S. Weir Mitchell, George R. Morehouse, William W. Keen, Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1864), 87.

[7] Ibid., 87.

[8] Ibid., 89.

[9] Ibid., 89.

[10] Shauna Devine, Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medici Science (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 144

[11] Ibid., 145

[12] Ibid., 140

About the Author

Dillon Carroll received his Ph.D. from the University of Georgia in August 2016, where he worked with Dr. Stephen Berry. He has published in The New York Times, and the Civil War History journal. He currently teaches at the University of Bridgeport and Hofstra University.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.