Table of Contents

How could a woman pass for a male soldier during the Civil War?

My name is J.R. Hardman, and I have been portraying a Civil War soldier at reenactments and living history events for the past five years, which is slightly longer than the Civil War actually endured.

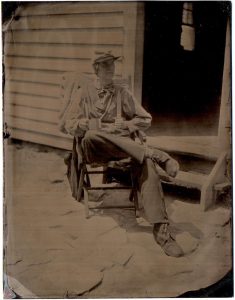

I have participated in over 25 events, learning about history and helping to educate the public about the life of a soldier. I generally appear in my butternut Confederate infantry uniform or my Yankee blue Federal artillery gear with the red stripes around the jacket. I’m almost six feet tall, a little larger in stature than the average serviceman of the period, but I’m lanky enough to play the roll of an undernourished private. I know the drill, and my officers say I do a decent impression.

I am also a 30-year-old woman. Off the battlefield, I’m the director of a feature-length documentary Reenactress, which is currently in production. Reenactress is about women like me who cross-dress to portray Civil War soldiers when reenacting.

Sometimes “reenactresses” are excluded from playing the military role. We are told we can’t pass as male. Unit commanders, event organizers, random commentators on Facebook, and even park rangers say we aren’t believable as men—That we look too much like women. Events often impose a “15-foot rule” that says, “If you’re identifiable as being a woman in uniform from 15 feet away, you may be asked to leave the field.”

When I first tried to start reenacting, the commander of a Georgia infantry unit said to me, “Talk to my wife. She’ll hook you up with a nice hoop skirt.” But I didn’t want to be a Southern belle. I wanted to portray a soldier. The same commander told me that women in a military role are frowned upon because they do a terrible job. I’ve heard things like, “You’re misleading the public about soldiers, and that’s just bad history!”

But that’s not entirely true. According to historians DeAnne Blanton and Lauren Cook Wike, between 400-1000 women served in the Civil War, clandestinely disguised in men’s attire.

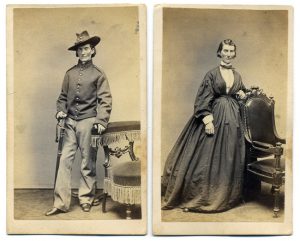

Sarah Rosetta Wakeman died of disease in a military hospital at the age of 21 and she was buried under her male alias, Lyons Wakeman. Her biological sex was never discovered during the war, and only recently exposed. She had already been passing as a boatman even before the war started. Jennie Hodgers joined the U.S. Army under the name Albert D.J. Cashier. Sarah Emma Edmonds became Frank Thompson. African American cavalry soldier, “George Harris,” revealed her true name to be Maria Lewis to an abolitionist woman living outside of D.C. Young wife, Frances Clalin Clayton, enlisted with her husband under the alias Jack Williams, and served in Missouri cavalry and artillery units. This is just a small sample of the women who “passed” in order to fight.

So how did they do it?

What I’ve gleaned from my personal experience passing for a male on the battlefield is that I’m not always that believable as a man in uniform. However, that doesn’t matter, because I am believable as a teenage boy.

At an event in southern Georgia, dressed in my vest, trousers, and slouch hat, I was approached by a middle-aged couple. The woman turned to her husband and asked, “Can you take a picture of me and him?” (Him meaning me!) After her husband took the photo, the woman continued the conversation by asking me, “Son, about how old are you? 17? 18?” and I replied, “No, ma’am. I’m about 30.” She was shocked about my age, but she never once questioned my “maleness,” and that’s when I understood. She believed I was a boy, not a man!

Passing for a teenage boy is a lot easier than passing for a full-grown, adult man. Men have beards, but boys don’t. Men are usually taller than women, but boys aren’t. Men have low voices, but boys often have a similar timbre and high pitch to their voices like women have. North and South, most Civil War soldiers were under 30—with some as young as 12. There would have been plenty of teenagers on the battlefield.

Furthermore, many of the women passing for men were young—enhancing their teenage-boy-ish-ness. Sarah Rosetta Wakeman (aka Lyons Wakeman) was only 19 when she enlisted in 1862. Jennie Hodgers (aka Albert D.J. Cashier) was 17, as was Maria Lewis (aka George Harris). Of the women soldiers we know of, Frances Clalin Clayton (aka Jack Williams), in her mid-twenties, was one of the oldest.

However, there are still some feminine physical characteristics that could give a woman soldier away: large breasts and wide hips, for example. With clever costuming techniques you can conceal your curves.

In the Victorian Era, people rarely appeared in public without being fully clothed up to the neck. Civil War uniforms were often ill-fitting, so female soldiers were able to pad their waists and hips to hide their curves, bind their breasts, and/or wear loose-fitting garments to help pass.

When Victorians looked at a person with short hair wearing trousers, they weren’t actively looking for secondary sexual characteristics to differentiate the woman wearing pants from the man wearing pants. Secondary sexual characteristics for women might include fuller lips, slighter jaws, or a lack of an Adam’s apple. Since women were almost never seen wearing anything other than a dress and it was practically unheard of for a woman at the time to have short hair, most Victorians would probably have assumed every short-haired, pants-wearing person to be male and left it at that. Today, with the variety of hair-styles and clothing options available to all genders, people look at others differently–using more subtle characteristics to make judgements about gender.

So the next time you watch a Civil War film or see a reenactment take the field, remember the women who served in disguise. Don’t impose your own 15-foot rule, but instead try to view the scene through Victorian eyes.

About the Author

J.R. Hardman is the Senior Tour Manager for Campus MovieFest (CMF), the world’s largest student film festival. She has helped to coordinate the festival for students at universities in over 15 U.S. States as well as in Mexico and the United Kingdom. She has also represented CMF at the Cannes Film Festival Short Film Corner in Cannes, France. Hardman also serves as the Technical Director for Camp Flix, a filmmaking summer camp for high school students ages 11-17. She has produced several short documentaries and fiction films including “Muslims in Love,” which premiered at the 2009 Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival, “The Coach,” which screened as part of the 2011 Arnold Sports Film Festival, and “Touching,” which was featured in several festivals including the 25th Anniversary Outfest: Los Angeles LGBT Film Festival. J.R. graduated from the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, CA, with a B.A. in Cinema/Television Production and Spanish. Reenactress is her first feature-length documentary film.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.