Table of Contents

“Voices of the Wounded” is a series of blog posts from the National Museum of Civil War Medicine detailing the experiences of wounded soldiers through their own words. Utilizing diaries, letters, memoirs, and other primary sources, theses posts will explore the feelings, thoughts, and actions of those wounded in action during the American Civil War. By examining the experiences of those struck down during the nation’s bloodiest conflict, we witness the hopes, the fears, the struggles and the cultural attitudes of soldiers in the Civil War. These words reveal the pain and suffering that are too often simplified to mere statistics.

The following accounts are a tiny sampling of the battlefield experiences of the wounded on three hellish July days: the Battle of Gettysburg.

More than 33,000 soldiers fell wounded at Gettysburg in the summer of 1863. In the weeks that followed, hundreds succumbed to their injuries. Others, with the assistance of military doctors and civilian volunteers, began the long road to recovery. Some returned to serve with their units for the remainder of the war. Still more journeyed home as disabled veterans with empty sleeves to mark forever their service in the American Civil War.

These are their first-person accounts.

“…I was shot in the right breast, the ball entering my lung, where it still remains. Capt. Hobert, of my regiment, made a detail with himself to take me off the field. They carried me over the pike, into a field near the old railroad grade, where they were compelled to surrender, and were taken prisoners to the rear, leaving me where you found me…”

Colonel John B. Callis, 7th Wisconsin, describing the moments when he was wounded near the “Railroad Cut” on July 1, 1863. The letter was written in 1893 to a North Carolinian who found Callis on the battlefield.

“While crossing a Clover Stubble field I was shot in the thigh (right) and soon fell to the ground helpless, unable to rise to my feet, the blood spurting from my wound in a torrent. My regiment passed on and left me, and the rebel line of battle passed over and while lying on the ground in rear of the rebels I received a shot in the right side. Just below and a little back of the right nipple and following the rib that it struck past out at the breast bone… I lay in the Clover field aforesaid until the evening of the next day…”

Private Edward Sloyer, 153rd Pennsylvania, describing his wounding on July 1, 1863 on Barlow’s Knoll at the northern edge of the battlefield.

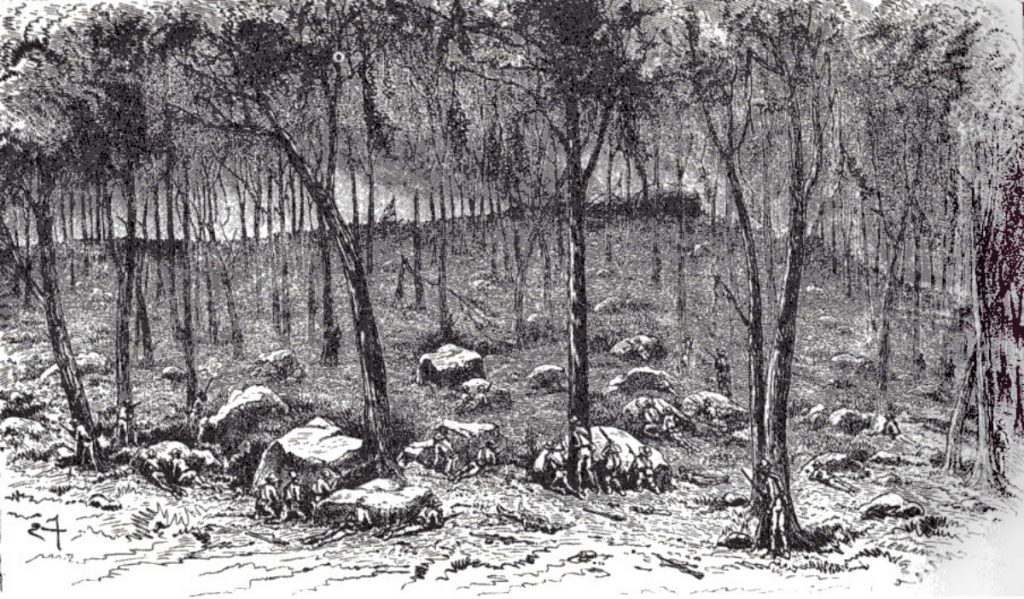

“I advanced up the hill to the right. In ascending to the right, I passed Col. Jack Jones, of my regiment, lying on his back with about half of his head shot off. I then passed one of Company K, of my regiment, lying flat on the ground, and he said to me: ‘You had better not go up there; you’ll get shot.’ I passed on to the top of the hill, and throwing up my old Enfield rifle, I was taking deliberate aim at a Yankee when a Minie ball passed through my right thigh.

I felt as if lightning had struck me. My gun fell, and I hobbled down the hill. Reaching the timber in the rear, I saw a Yankee sergeant running out in the same direction, being inside our lines. I called to him for help. Coming up, he said: ‘Put your arm around my neck and throw all your weight on me; don’t be afraid of me. Hurry up; this is a dangerous place.’

The balls were striking the trees like hail all around us, and as we went back he said: ‘If you and I had this matter to settle, we would soon settle it, wouldn’t we?’ I replied that he was a prisoner and I a wounded man, so I felt that we could to terms pretty quick…”

Private John W. Lokey, 20th Georgia, describing his wounding at Culp’s Hill on July 2, 1863 in an article published in Confederate Veteran in September 1914.

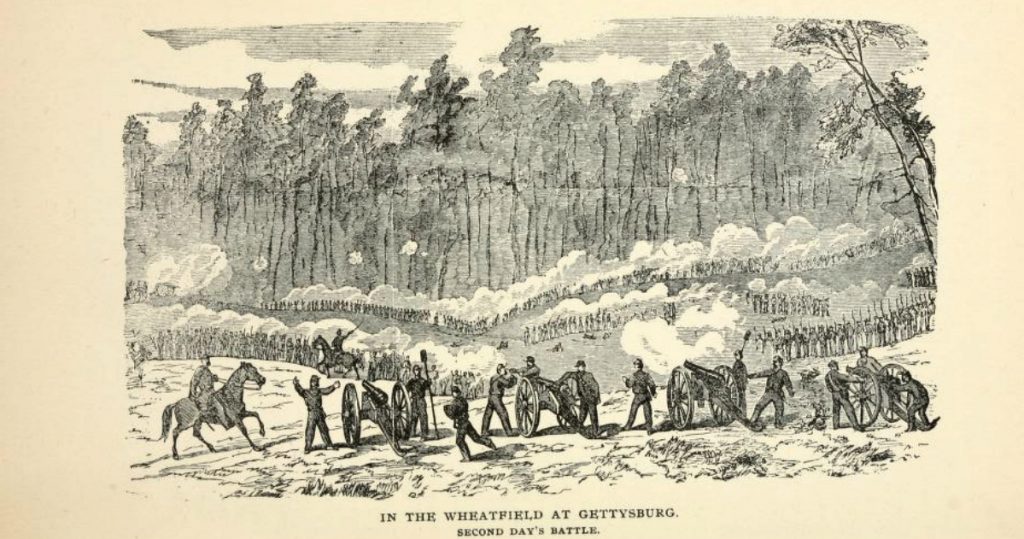

“As we pushed forward a bullet struck my right arm and passed through it. As we charged into the wheatfield a shell exploded and shattered my right leg and killed two of my comrades. When I was shot in the arm, the feeling was the same as though I had been struck on the elbow – a feeling of numbness came into the arm – and I turned to the comrade by my side and asked him why he had hit me.

He said: ‘I did not hit you, but you have been shot and you had better go to the rear.’ I laughed at him and said I was not hurt bad enough to do so. Shortly after I was injured, as I have mentioned, by the shell.

After my leg was shattered I fell down, laying for a few minutes unconscious, and when I came to my senses I was surrounded by the enemy…”

Private Jacob Henry Cole, 57th New York, detailing his wounding on July 2, 1863 during the fighting in the Wheatfield in his memoir, “Under Five Commanders: Or, A Boy’s Experience with the Army of the Potomac.”

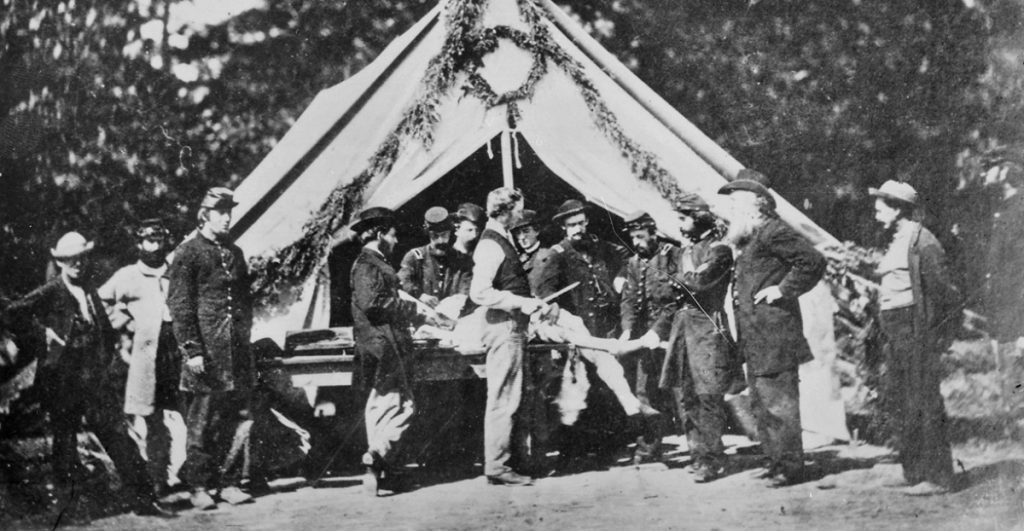

“I write simply a line to inform you of my condition. In an engagement Friday afternoon near Gettysburg, about 3 P.M. I received a wound in my left arm. It was broken by a musket ball above the elbow. W. F. Landford of my company was near me when I was wounded he having been taken prisoner after the battle was about over assisted me from the field I lay out that night but was furnished with blankets and otherwise very kindly treated by the enemy…

I reached this place (a Federal Hospital about 2 miles from town) Saturday the 4th, and my arm was [amputated] that afternoon by surgeons with whom I had all confidence. It was taken off at the middle third and of course does not leave much – save for 6 inches. I had no knowledge of the going on of the operation – as I was under the influence of chloroform, but it was pretty painful afterwards – but is I think getting on very well.”

Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Franklin Little, 52nd North Carolina, from a letter written to his wife written on July 9, 1863. Little was wounded during the infamous Confederate charge on Union lines on July 3.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.