Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

“The scene is silent and sad,” wrote General Samuel R. Curtis of the Battle of Pea Ridge. ”The vulture and the wolf have now the dominion, and the dead friends and foes sleep in the same lonely graves.” On three bloody days in March 1862, more than 4,000 Union and Confederate soldiers fell in rural northwest Arkansas. The isolation of many western battlefields from larger cities where shelter and supplies were more readily available made life extremely difficult for wounded soldiers.

By the end of February 1862, Union forces had nearly cleared Missouri and northwestern Arkansas of Confederate troops. One more military victory in the area would solidify Union control of the region. Confederate General Earl Van Dorn initiated the Battle of Pea Ridge to prevent that from happening.

When the battle began on the night March 6, 1862 the Union army operating in the area, the Army of the Southwest, was dangerously low on medical supplies, and their nearest stockpile was in St. Louis, MO, about 300 miles away. The head surgeon of the Army of the Southwest, W.C. Otterson, went there to resupply in early February, but had not yet returned when fighting broke out.

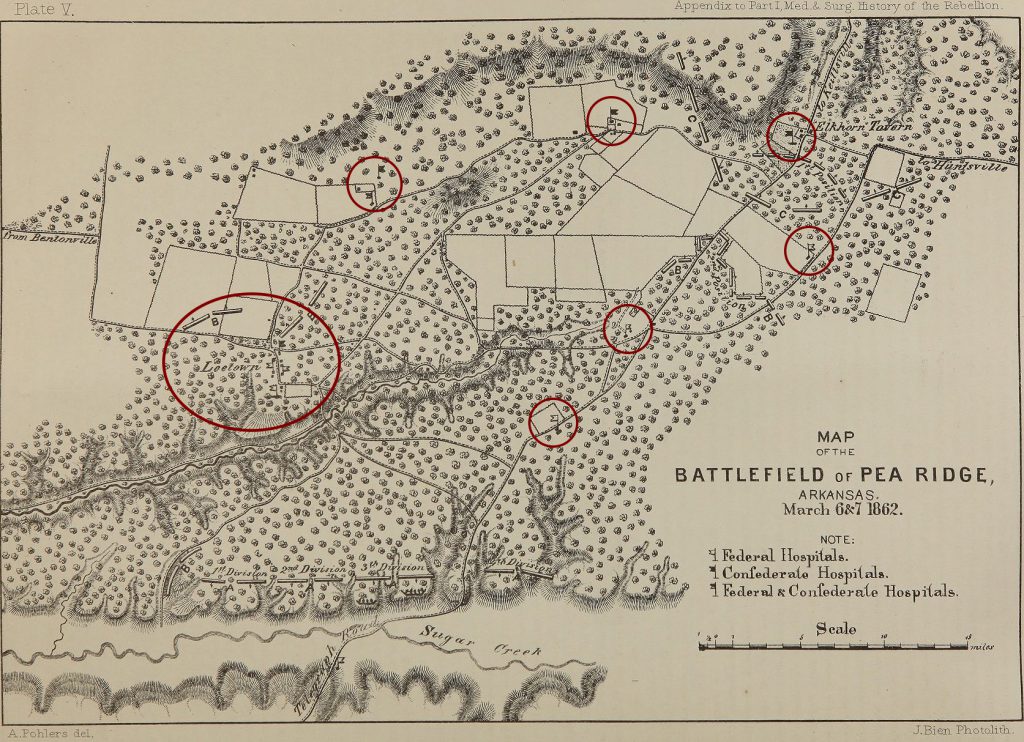

When the wounded streamed toward the rear during the first full day of battle on March 7, surgeons needed a place to treat them. The largest settlement near the battlefield was called Leetown, but being on the American frontier meant it only contained 15-20 one-story buildings.

Union surgeon D.L. McGugin wrote that Leetown “contained but few of the ordinary domestic appliances, and were wholly wanting in the usual necessaries found in more settled regions.” McGugin went on to report that “all the houses within three miles of the field were taken for hospitals. Some of these sheltered both our own wounded and those of the enemy.” There were simply not enough buildings to shelter all the wounded.

In addition to having no kitchens or outhouses, Leetown was not particularly close to a source of fresh water. “We were forced to bring [water] in casks from the creek, half a mile distant,” Dr. McGugin remembered.

Because the Battle of Pea Ridge took place in a remarkably inaccessible area, typical medical regulations for proper space per patient and cleanliness could not be followed. McGugin described his experience treating the wounded during and after the battle:

At Leetown I was soon engaged…in attending the wounded, in a building formerly occupied as a small store…the wounded were brought in more rapidly than there was room for their reception. This building would accommodate only about thirty-five patients, yet it had a greater capacity than any other building in the village.

After the first day of combat, surgeons were already overwhelmed by the lack of supplies and by the vast number of wounded. Yet, another day of battle was to come. During the night of March 7, while both armies prepared for combat, the medical corps fought to save lives. McGugin recorded that the surgeons “where they were fortunate enough to procure light, proceeded with their work, and few, if any, of them slept.”

Fighting on March 8 resulted in a Union victory. With the Confederate army in full retreat, the battlefield and its wounded were left in the hands of Union forces. Orders soon went out for Union surgeons to begin taking care of the enemy’s wounded remaining on the field. “[Our army] stampeded and left us here with our sick and wounded men,” wrote a Confederate surgeon left behind to care for his army’s wounded. “…for two days we had nothing to give our poor fellows but parched corn and water. Every Federal officer and man has treated us like gentlemen, and General [Curtis] told me that so long as he had a loaf of bread we should have half of it.” When Confederate soldiers were wounded and thus no longer a threat, it was not uncommon for Union medical authorities to look after them in this way and vice versa.

With the battle over, the pressing question became how to care for approximately 2,300 wounded soldiers (from both sides) without the necessary resources to do so. Soon after the battle, as many wounded soldiers as could be transported via wagon were ordered to Cassville, Missouri to alleviate the overcrowding in Leetown. It was a twenty mile journey that took three to four days to complete over roads of exceedingly poor quality

Cassville provided conditions little better than those seen at Leetown, however. The report of a Western Sanitary Commission agent described the scene weeks after Pea Ridge was over:

At Cassville I found two large tents, six buildings, including the Court House and Tavern, used as hospitals. The patients were lying on the floors, with a little straw under them, and with knapsacks or blankets under their heads as pillows. They had no comforts of any kind, no change of clothing, but were lying in the clothes they fought in, stiff and dirty with blood and soil.

It quickly became clear that properly caring for the wounded from Pea Ridge would not be possible without larger buildings and more resources.

Cassville represented the best medical care most of the wounded men would get. Well-furnished Army hospitals in St. Louis were 300 miles away and the nearest railroad terminus with passage to St. Louis was 250 miles away in Rolla, Missouri. Springfield, Missouri was the closest city of any size, but that was still an 80 mile trip over poor roads where guerrilla bands roamed with relative impunity, making any extended travel through the countryside hazardous.

By March 25, more than two weeks after the battle, agents and supplies from the Western Sanitary Commission began arriving at Cassville and other nearby hospitals in large quantities. They provided desperately needed medical supplies, bedding, and clean clothes to those convalescing from battlefield injury and disease.

Following the Battle of Pea Ridge, the Union medical department and the Western Sanitary Commission worked to prevent a medical disaster similar to Pea Ridge where the army was caught without adequate stockpiles of medical supplies or easy access to long term care facilities. While medical care in rural Missouri and Arkansas could not match that seen in the Eastern Theater, by 1864 more than 70 hospitals had been opened in the region to offer some degree of care to sick and injured soldiers.

Learn more from John Lustrea, one of the post’s co-authors

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Authors

John Lustrea is a member of the Education Department and the Website Manager at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He earned his Master’s degree in Public History from the University of South Carolina. Lustrea has previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park during the summers of 2013-2016.

James Horn is a 2014 graduate of Shepherd University with a degree in Civil War History. He has worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park, and the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. In 2017 he published the book World War I and Jefferson County, West Virginia.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.