Table of Contents

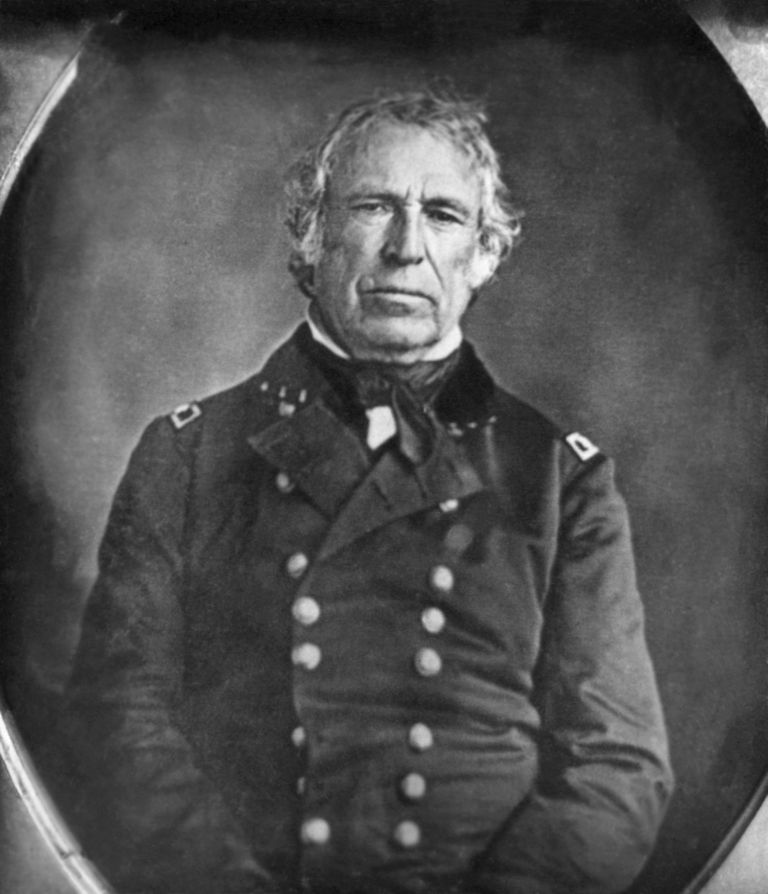

On the evening of May 8th, 1846, Lieutenant William S. Henry took a few spare moments to survey the ground a few miles outside of modern-day Brownsville, Texas, where the first battle of the United States’ war with Mexico had just taken place. Although the losses of the U.S. forces under General Zachary Taylor were small compared to that of the Mexican army under General Mariano Arista, Lt. Henry was struck by the effects of the artillery-dominated battle:

“The wounds of the men were very severe, most of them requiring amputation of some limb. The surgeon’s saw was going the livelong night, and the groans of the poor sufferers were heart-rending. Too much praise can not be bestowed upon our medical officers for their devotion and prompt action. It was a sad duty for them.”[1]

A long night on the battlefield of Palo Alto was only the beginning for the American medical staff. In 1846, the United States Army Medical Department was poorly equipped for a large-scale war of conquest. Chronically understaffed, plagued by logistical and organizational troubles, and operating under unfamiliar environmental conditions, the experience of military medicine in the first Mexican city occupied by the U.S. Army provides a useful case study of the problems it faced throughout the war’s duration.

Although the Mexican War preceded the Civil War by less than fifteen years, it left a murky precedent for what Americans could expect from wartime disease, injury and death. Mortality rates were horrifying, if not remarkable, compared to earlier 18th and 19th century conflicts: on average, an American volunteer regiment could expect to lose a little over a tenth of its men in the Mexican War. Of this number, seven times as many died from illness as from battlefield injury. Historian James McCaffrey makes very plain the difference in scale between the U.S. Civil War and the U.S.-Mexican War by noting the number of men killed in one day at Antietam exceeded the total number of those lost in the war with Mexico. Statistically, however, a soldier’s odds of surviving the Civil War were slightly better. The fact that Civil War soldiers were only twice as likely to die of disease as from wounds was nevertheless due more to deadlier battlefields than drastically improved military medicine.[2] Familiar in some ways and distant in others, the Mexican War was the background against which Americans had to compare their Civil War, and the occupation of Matamoros is a telling case study.

General Arista abandoned the Mexican port city of Matamoros following the consecutive defeats at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, leaving behind the wounded that could not be transported. When General Taylor’s army marched into Matamoros on May 12th, they found 300-400 Mexican wounded crowded into four or five smaller hospitals, in conditions that horrified U.S. Army surgeon and general hospital director Nathan Jarvis. Many had undergone hasty amputations in the field, and many had already died of tetanus. A Mexican account published in 1848 recounts that “Among them there were some who, upon knowing of the army’s retreat, left the hospitals and followed, dragging their bodies on the ground and leaving a trail of blood. Those unfortunates preferred every kind of suffering to being left helpless in a population in which they feared the victor would treat them with cruelty.”[3] As it happened, the U.S. Army’s official policy was relatively humane. By General Taylor’s orders, captured Mexican wounded were committed to the care of local Mexican surgeons, presumably civilians. Jarvis expressed confidence in their skills, but like their American counterparts, they were undermanned and overwhelmed by the sheer number of wounded and limited resources.[4]

Many of the American wounded from Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma remained at previously established hospitals Corpus Christi and Point Isabel 160 miles north on the Texas coast.[5]

Disease posed far greater threat than the battlefield. In addition to ubiquitous camp diseases like dysentery that had hounded Taylor’s army before it ever crossed the Rio Grande, the rainy season and its mosquito-borne malaria came directly on the heels of the city’s occupation and further compounded public health woes for all of Matamoros’ residents.[6] Smallpox, too, carried off its share of victims. Although all American soldiers were supposed to have been vaccinated against the disease upon entering the army, volunteers sometimes fell through the cracks in the rush to deploy troops, and one army surgeon complained his supply of the vaccine had been ruined by the Mexican heat.[7] Most to be feared was the deadly yellow fever, and with the help of correspondents on other battlefronts in Mexico and from coastal U.S. cities like New Orleans and Mobile, the bluntly titled English language newspaper The American Flag carefully tracked the fever’s progress throughout the Gulf of Mexico.[8]

In part for the protection of Mexican civilians, the Army encamped outside of city limits. But the sick spilled from the regimental hospital tents into the city itself. The Medical Department set up several general hospitals, including one specifically to isolate smallpox cases, but overcrowding, insufficient supplies, and poor ventilation seemed inescapable.[9] Soldier Thomas Tennery visited one of these hospitals in September of 1846, over three months after the battle, and described the situation as such: “It presents quite a sorrowful aspect…there are not beds or mattresses enough for the sick; consequently a great many have to lay on the brick floor, without anything but a blanket underneath them. The care taken of them is according to the nurse’s disposition.”[10] The quality of nurses and hospital attendants could vary widely—capable hospital attendants tended to be few and far between.[11] In many cases, a sick man’s best advocates and caretakers were his messmates.[12]

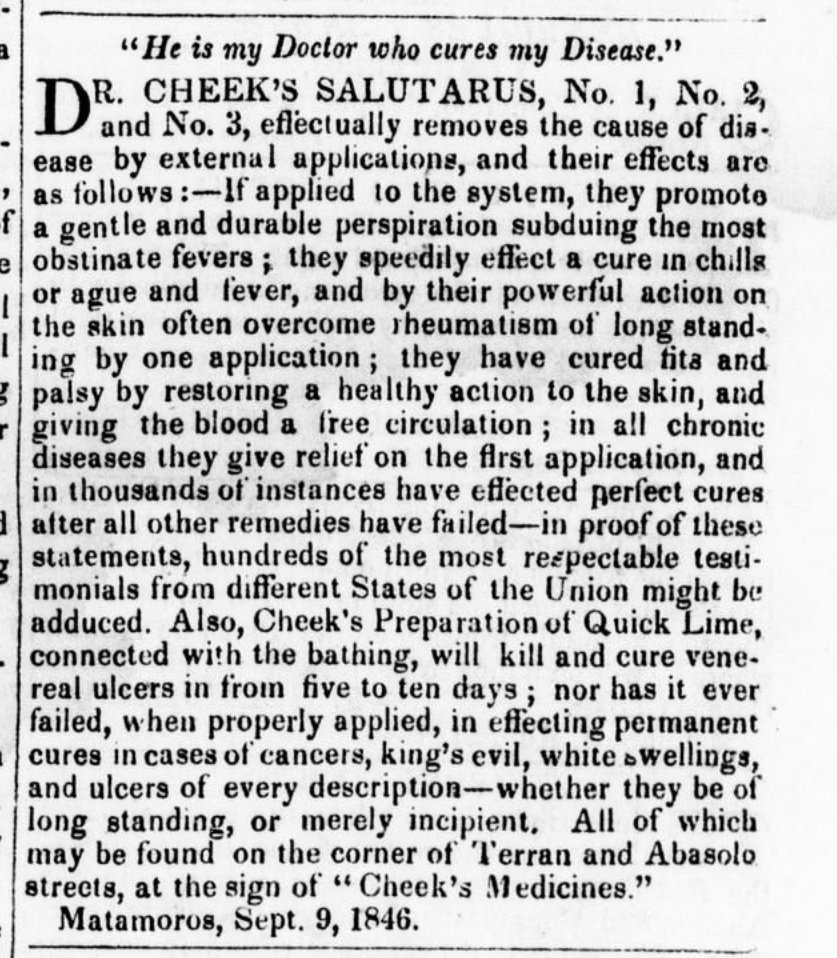

Many soldiers attempted to avoid the army hospitals altogether when they fell sick. If they could afford it, some hired civilian doctors, whether American, European, or Mexican. More resorted to self-treatment with a variety of remedies, including dietary restrictions, roots, herbs, teas, and various mixtures of alcohol, laudanum, or opium.[13] Enterprising merchants filled The American Flag with advertisements for patent medicines like “Dr. Cheek’s Salutarus,” sold out of its own storefront on the corner of Terán and Abasolo streets.[14]

Ailing officers could take lodgings in the city to be closer to medical treatment, either from the Army surgeons or civilian doctors. Colonel Samuel Curtis of the 3rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment had been suffering from diarrhea for over a month when fever and incapacitating headache prompted his doctor to advise moving into city limits where he could receive daily attention. Curtis found purchasing suitable lodging harder than he expected. The “public houses” were all full, and the U.S. Quartermaster, who Curtis accused of partiality towards regular officers, only offered a location in which all the neighboring rooms were “filled with dead and dying.” Repulsed, Curtis wrote that he would rather die in his own tent. He lamented the regulations prohibiting the Army from forcibly requisitioning quarters belonging to the Mexican residents, claiming that “Such a rule is inconsistent with reason and restricts the quarters of the sick so that 15 to 20 are crowded into one room and no doubt adds to the mortality that prevails.”[15]

Wars take place just as much in occupied cities and hospitals behind the lines as they do on the frontlines, and the war kept moving forward and often through Matamoros. Important for logistical support of the U.S. Army’s operations deeper in the Mexican interior, Matamoros remained an occupied city with a distinctly American commercial flavor, even after the main body of Zachary Taylor’s army had moved on. Its darkest hour had mercifully passed.

Endnotes

[1] Lieutenant William S Grady, “War Has Commenced,” in To Mexico With Taylor and Scott, 1845-1847, edited by Grady McWhiney and Sue McWhiney, (Holtham, MA: Blaisdell Publishing Company, 1969), 35-36.

[2] James M. McCaffrey, Army of Manifest Destiny: The American Soldier in the Mexican War, 1846-1848 (New York: New York University Press, 1992), p. 139; Richard Bruce Winders, Mr. Polk’s Army: The American Military Experience in the Mexican War. (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1997), 139.

[3] Ramón Alcaraz, et al, eds, Apuntes para la Historia de la Guerra Entre México y los Estados Unidos, 1848 (Mexico City: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1991), p. 91.

[4] Mary C. Gillet, The Army Medical Department, 1818-1865, (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1987), p. 99-101. Accessed 3/1/2019. https://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/civil/gillett2/gillett.html

[5] Gillet, 99.

[6] Gillet, 101-102.

[7] Winders, 146.

[8] The American Flag, (Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico), Vol. 1, No. 36, Ed. 1 Saturday, September 26, 1846, p. 3. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth478819/: accessed January 26, 2019), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Abilene Library Consortium.

[9] Gillet, 101-102.

[10] D.E. Livingston-Little, ed, The Mexican War Diary of Thomas D. Tennery (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 28.

[11] Gillet, 97.

[12] See Joseph E. Chance, ed, Mexico Under Fire: Being the Diary of Samuel Ryan Curtis, 3rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment During the American Military Occupation of Northern Mexico, 1846-1847 (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1994), p. 24.

[13] Winders, 156-157.

[14] The American Flag, (Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico), Vol. 1, No. 36, Ed. 1 Saturday, September 26, 1846, p. 2. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth478819/: accessed January 26, 2019), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Abilene Library Consortium.

[15] Chance, p. 31-32.

About the Author

Michelle Herbelin is a native of Waco, Texas and has been an enthusiastic student of history for as long as she can remember. Michelle graduated from Baylor University in 2015 and went on to receive her Master’s degree in History from the University of South Carolina in 2018, where she plans to return to pursue her PhD. Michelle specializes in early 19th century United States, Mexico, and Texas history, and her current research focuses on sensory experience and rhetoric during the Texas Revolution.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.