Table of Contents

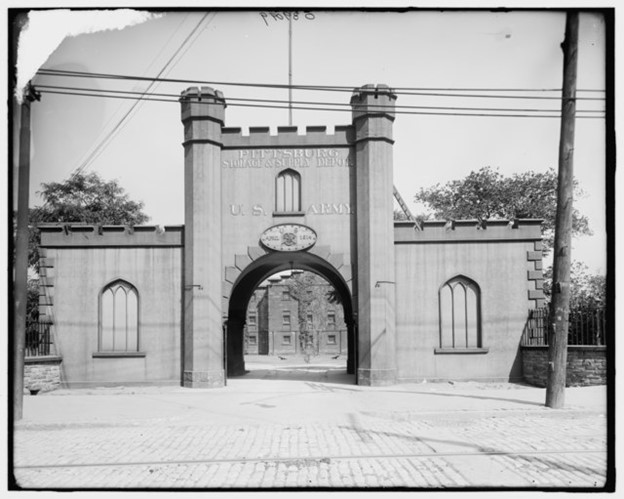

September 17, 1862, the bloodiest single day in American history. As the guns were firing and soldiers were charging into battle near the small town of Sharpsburg, Maryland along Antietam Creek, the city of Pittsburgh was about to experience the destruction of that day a little closer to home. The Allegheny Arsenal in Lawrenceville, PA just outside of Pittsburgh was originally built in 1814 and was critical in the U.S. Army supply chain to the West. The Arsenal was spread out across a 38-acre complex manufacturing gunpowder, cartridges, harnesses, and other valuable equipment critical to the war effort.

On the day of the explosion, 186 workers were on site, 156 of those workers were young girls and women. Many children worked in arsenals and factories across the country throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th century as child labor laws had not been established yet. In the case of the Allegheny Arsenal, there used to be primarily young boys and men working on the factory floor, however, many were fired because “supervisors often caught the boys with matches… after three warnings to get rid of the smoking material, the arsenal dismissed most of the boys and hired women and girls instead…”[1] Supervisors even preferred to hire the young girls as they were reportedly more reliable and they did not smoke.

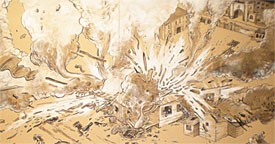

As reports came in about the bloodshed at Antietam, Pittsburgh and the Allegheny community were recovering from their own tragedy. The Daily Ohio Statesman reported the following day, “The Explosion at Allegheny Arsenal – 75 or 80 Boys and Girls Killed… The scene was appalling, dead bodies lying in heaps as they had fallen… Up to the present time sixty-three bodies have been taken from the ruins.”[2] Newspapers all the way in Wisconsin had heard about the explosion, “One explosion followed by another until the entire building was destroyed… Those who could not escape at the time were burned up… The cause of the explosion is not known, but it is admitted by all to be accidental.”[3]

On that fateful Wednesday afternoon, the workers were making cartridges as normal, and many were lined up to collect their wages as it was payday. At 2:00 PM, the first explosion went off. Panic struck the workers and there was a rush to exit the Arsenal campus. Shortly afterwards a second explosion occurred, and then a third moments later. The fire spread quickly throughout the building known as the Laboratory. The fire was so intense that some witnesses reported seeing bright white bone where charred flesh would have been. As the fires spread, many of the cartridges that had already been assembled started to go off followed by several hundred Parrott-gun projectiles. Fire brigades began to show up from both Lawrenceville and the surrounding communities in an attempt to quell the massive fire but to no avail. 19th century fire brigades were no match for the monstrosity in front of them. Despite their best efforts, they could only watch as the Laboratory blackened and crumbled.

By the time the fires had died down, the aftermath of the explosion left 78 killed and over 150 injured. The Allegheny Arsenal Explosion became the worst industrial accident and the worst civilian accident during the Civil War. One of the girls killed in the blast was Katie McBride, her father Alexander was one of the supervisors of the Arsenal and some of the blame was placed on him for the explosion despite him trying to mitigate the chances of one.

Colonel John Symington was the commandant of the Arsenal and had ordered a macadamized road constructed on the grounds, “this type of road contained pieces of hard, flinty stone, and the workers warned management about the potential for an explosion.”[4] Alexander McBride heard these warnings and had woodchips and sawdust spread over the road, however, Col Symington ordered it to be removed. He also refused to let the workers take a half day to clean the road of spilled powder. McBride even claimed that the E.I. DuPont company was reusing old gunpowder barrels, an undesirable practice as the gunpowder deteriorates the barrels after multiple uses.

Many of those wounded in the explosions were taken to nearby West Penn Hospital, about a mile and a half away, including Joseph Frick, the wagon driver who is believed to have inadvertently started the fire leading to the blast. The cause of the blast was believed to be caused by either the iron horseshoe or iron-rimmed wagon wheel creating a spark and setting fire to the powder on the ground. This theory was also confirmed by eyewitness Rachel Dunlap who testified that “a flame shot up from between the wagon wheel and his one horse’s rear hoof.”[5] Frick was thrown from his wagon and suffered a suspected concussion. Many newspapers of the time did not cover the stories of those wounded in the blast, rather, they reported on the carnage which ensued. However, there are still some existing accounts of people performing rudimentary triage on the scene.

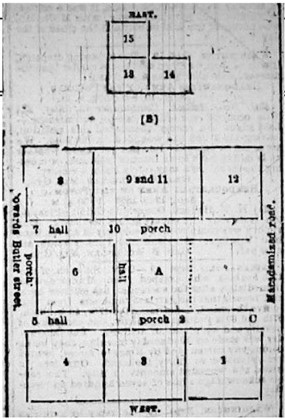

One such person was Alexander McBride, Arsenal superintendent, who heard the explosions and witnessed the roof collapse on building #6, killing his daughter. Despite witnessing the death of his daughter, McBride took to helping other wounded girls douse the flames on their dresses, provide fresh clothes, and assist in trying to stop the spread of the fires.[6] The map in the article referenced is based on the drawings done by Alexander McBride after the explosion and an 1859 Ordnance Department survey, later reprinted in the Pittsburgh Daily Post in the wake of the explosion.

Another person who was on the ground performing triage was Reverend Richard Lea of the Lawrenceville Presbyterian Church, one block from the arsenal. After the explosion, which destroyed the windows in his church, Rev. Lea ran across the street and jumped the wall of the Arsenal to provide aid and comfort for the dying. In a sermon dedicated to the victims of the explosion decades later, Rev. Lea had this to say about those who provided aid to the wounded, “But amidst all this dismay and fearful consternation and apprehension of still worse to come, when the magazine should explode, there were many who entered the gates and climbed the walls, determined to aid, or die in the attempt.”[7]

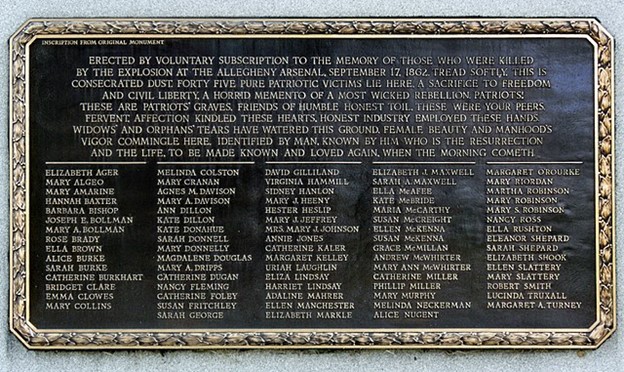

A monument to those killed in the blast was placed on the grounds of the Arsenal a few weeks after the explosion. Forty of the victims were so severely burned their bodies were unrecognizable and unidentifiable. These were placed in forty black caskets and there was a separate casket for the mix of limbs and body parts that could not be paired with its original owner. In 1928, the memorial was moved to the Allegheny Cemetery where the names of all those killed were listed and buried at the foot of the monument.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021. He is currently pursuing a Masters in American History from Gettysburg College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Sources

[1] Gormly, Kellie. “Sept. 17, 1862-the Day Pittsburgh Exploded.” Pittsburgh Quarterly, January 11, 2021. https://pittsburghquarterly.com/articles/sept-17-1862-the-day-pittsburgh-exploded/.

[2] “The Explosion at Allegheny Arsenal – 75 or 80 Boys and Girls Killed.” Daily Ohio Statesman, September 18, 1862.

[3] “Explosion of the Allegheny Arsenal – Over 75 Persons Killed.” Mineral Point Weekly Tribune, October 1, 1862.

[4] “Allegheny Arsenal Explosion.” History of American Women, April 3, 2014. https://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2014/04/allegheny-arsenal-explosion.html.

[5] Powers, Tom. “View of behind the Scenes of the Allegheny Arsenal Explosion: Western Pennsylvania History: 1918 – 2019.” View of Behind the Scenes of the Allegheny Arsenal Explosion | Western Pennsylvania History: 1918 – 2019. https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/59183/58908.

[6] Powers, Tom. “View of behind the Scenes of the Allegheny Arsenal Explosion: Western Pennsylvania History: 1918 – 2019.” View of Behind the Scenes of the Allegheny Arsenal Explosion | Western Pennsylvania History: 1918 – 2019. https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/59183/58908.

[7] Condon, Rich. “The War in Their Words: The Allegheny Arsenal Explosion.” HistoryNet. HistoryNet, January 1, 2022. https://www.historynet.com/the-war-in-their-words-the-allegheny-arsenal-explosion/.