Table of Contents

Nearly 30,000 prisoners occupied the prison at Andersonville, Georgia in July 1864 when Dr. John M. Howell arrived. Born and raised in nearby Houston County, Georgia, Dr. Howell enlisted as a surgeon in the Confederate Army in April 1862 and served until the end of the war. By mid-summer 1864 he had been briefly reassigned to the Union hospital at the infamous Camp Sumter Military Prison. The newly constructed prison opened on February 24, 1864, and by the end of July it had claimed the lives of 4,576 Union soldiers. As Dr. Howell approached his newly assigned post, the sweltering summer heat inflamed the smells and cries coming from the stockade-styled prison pen. He quickly took note of the “hundreds of blue coats making their way through two lines of guards to the prison gates,” and described the prison as “the most uninviting place of which a Yankee knows anything about.”

Dr. Howell served as Acting Assistant Surgeon at Andersonville, and was a member of a small 15 person medical staff, with Dr. Isiah White at the helm responsible for caring for a prison population that ranged from 28,000 to 33,000. During his tenure at the ill-reputed prison, Dr. Howell wrote letters to his wife describing his duties, the conditions of the prisoners, and difficulties the medical staff encountered. His writings allow a unique opportunity to observe hospital organization at the deadliest ground of the Civil War.

Upon his arrival, Dr. Howell described the dilapidated conditions he found:

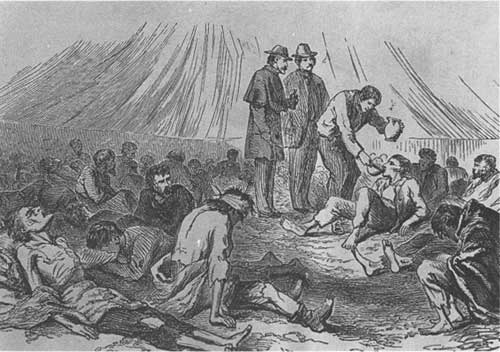

“I met up with Dr. Crodille, raised in Greene, who asked me to walk with him to the Yankee hospital. I did so, and such objects in the way of men I never saw before. Sick and emaciated, naked, ragged and dirty – some on straw with a blanket under them – some without either – some that will die tomorrow, some today – some dying with another whose face is turned toward him breathing his last. I saw too some awful cases of gangrene – cases where the flesh has been destroyed to the bone. But before you can imagine such pictures, you must first see some sufferings like these. I can give you no idea of them. In comparison an ordinary death is pleasant to contemplate.”

Each surgeon was paired with an assistant, usually a paroled Union prisoner, which brought the hospital staffing to a minimum 30 person medical team. According to Dr. Howell, each surgeon was assigned to examine around 500 prisoners each, per day. They were only allowed to admit roughly 200 prisoners to the hospital every day, leaving hospital staff to turn away many who desperately needed medical attention. The hospital itself was haphazardly divided into wards with each one filled past capacity. Those who were admitted into the hospital were the sickest of the sick and their next destination was often the prison cemetery.

The number of prisoners turned away from being admitted to the hospital devastated morale inside the prison stockade. In some cases, prisoners who were miserable with their inflicted illness would speed up the process of dying by taking their own life. Others, like the case of Griggs Holbrook, held on to hope until their last moments. Suffering from chronic diarrhea, Holbrook focused his attention on his comrade Jones Sherwood – both of the 76th New York Infantry. Holbrook cared for Sherwood who was also rapidly growing sicker each day, and noted in his diary, “After carrying Jones over to the hospital several times – [I] finally succeeded in getting him in.” Three weeks later Sherwood was laid to rest in the red Georgia soil. Holbrook, who stayed positive through his diary, joined Sherwood in the prison cemetery later that month.

As summer progressed, the prison population peaked at 33,006 on August 9, 1864. By the end of the month, the medical team at Andersonville had decreased by three while the death rate at the prison steadily rose. Dr. Howell had a daily routine in play within a month after arriving. His wife wrote him a letter expressing curiosity about what he did on a day-to-day basis, to which on August 29, 1864 he replied:

“In the first place I go to the chief surgeon’s Hd Qtrs about 8 A.M. There I ascertain the number of sick to be admitted to the hospital. This number, divided by twelve, which is the number of physicians now on duty at the stockade, which is the amount each one is to admit. The number to be admitted depends upon the capacity of the hospital the day previous. We can only fill up the vacancies. After knowing what the number to be admitted to the hospital is, I have only to select that number from the sickest cases, make an entry of it by writing private or not (the grade). I have a clerk do the writing. (He) gives each case, as the prisoners call it, a label, and I have them be sent to the hospital. I forgot to mention that the entry has the diagnosis and the word hospital written on a line corresponding to the date of admission. I now prescribe for the other cases, my clerk writing the prescriptions. I am usually engaged from 8 to 12.”

The medical staff at Andersonville never caught a break during the month of August, which was the deadliest time at the prison with nearly 3,000 Union soldiers dying in that month alone. General William Sherman unexpectedly brought relief to the prison hospital when he captured Atlanta on September 2, 1864. Evacuation orders were issued on September 7th, relieving the prison of over three-fourths of its population in just two months, thus minimizing the number of patients in the hospital. Several physicians at Andersonville, including Dr. Howell, were critical of their superiors. Some accused Dr. White of withholding medical supplies and others complained they were unsure of who was really in charge of the hospital, Dr. Isiah White or Captain Henry Wirz.

Overall, Dr. Howell’s letters combined with testimonies from the trial of Henry Wirz gives us just a glimpse into the commotion outside the stockade among Confederate staff. Working at the most crowded and deadliest ground of the Civil War was no easy feat for any member of the staff, and like the prisoners locked inside the stockade walls they were eager to get home. Signing off on his last preserved letter, Dr. Howell wrote, “I want to see you all very much and hope the time is not too far distant when I might be allowed that privilege.”

About the Author

Jennifer Hopkins is a Park Guide at Andersonville National Historic Site located in southwest Georgia. After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree in History from Wesleyan College, Macon, GA, she sought positions within the National Park Service (NPS). Jennifer has been employed with the NPS for three years and is looking forward to many more years of adventures.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.