Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

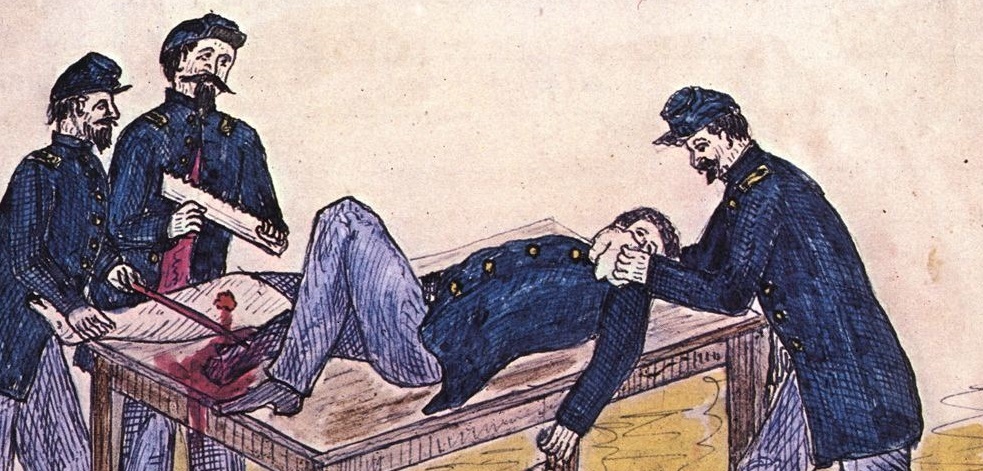

“See here, Doc., if you’re goin’ to take that leg off, you’d better be about it-I’m comin’ to.”

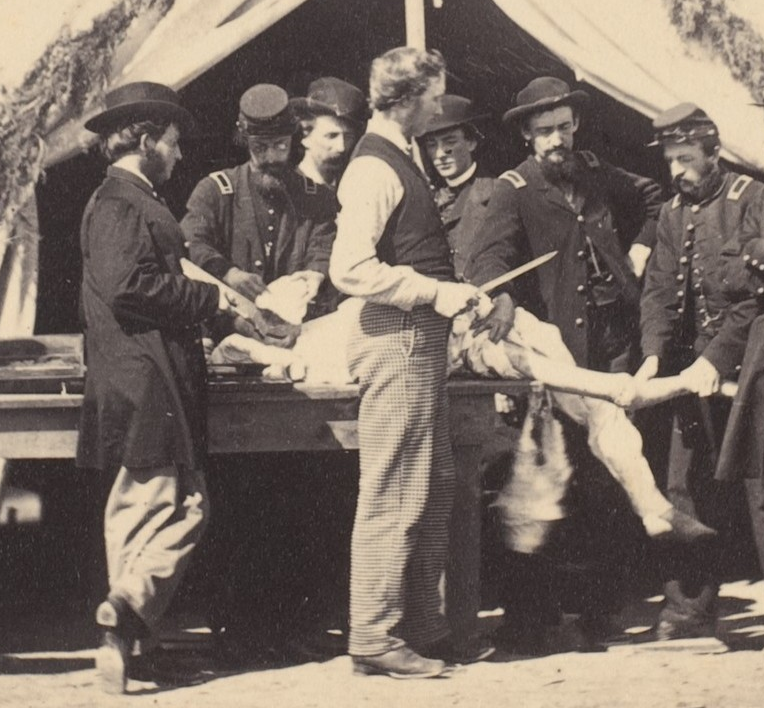

These were the frustrated and possibly fearful words of a wounded soldier in the aftermath of the 1863 Battle of Honey Springs. The unnamed man was so grievously wounded that army surgeons opted for amputation. Through the course of the Civil War he and 60,000 others would go under the knife and never be the same.

Understandably, he was worried. To suffer such a painful operation without anesthetics was a terrifying prospect. Much to the surprise of the patient, “his leg was already off and the stump ‘done up in a rag,’ he raised himself a little on his elbows to look and see if such was really the case, remarking, ‘Is that so? I didn’t know a thing about it.’”[1] This was the miracle of anesthesia.

You may have heard that surgeons did not use anesthesia in the Civil War. That’s untrue. Sometimes the term “anesthetic” is confused with “antiseptic.” Anesthetics were an absolutely vital tool in the arsenal of Civil War medicine. For us to fully understand the role of anesthesia in the Civil War, we have to explore its history in the antebellum period, the importance placed on it by both North and South, and the methods by which it was administered. This comfort to the wounded and boon to the surgeon was perhaps the most important medicine of the period.

To begin this exploration, we must first define “anesthetics” and “anesthesia.” Anesthetics are those substances used to induce the state of general anesthesia. General anesthesia applies to the entire body and results in unconsciousness. Local anesthesia is pain relief in a particular area. While local anesthesia was performed in the Civil War (powdered opium could be applied to open wounds, for example) I will be focusing on general anesthesia as the most commonly applied of the period. For patients and surgeons anesthesia offered three vital results:

- Analgesia [painlessness]

- Amnesia [memory loss]

- Muscle Relaxation

For patients, analgesia and amnesia are a godsend when subjected to an otherwise traumatic and painful surgical procedure. The muscle relaxation made it easier for them to operate, especially in tricky procedures requiring precise incisions.

Anesthetics exploded onto the scene about 15 years before the Civil War and were a distinctly American invention. The earliest successful experiments may have been conducted by Dr. Crawford W. Long of Georgia. As early as 1842 he used anesthesia in surgery, but he made no effort to make his discovery known until years after others shared their discoveries. He was followed shortly thereafter by Horace Wells, a Massachusetts dentist who experimented with nitrous oxide. Wells did try to draw attention to his discovery. His public demonstration in 1845 was an apparent failure. Wells’ patient did not fully experience muscle relaxation and was heard moaning in the hall. Observing medical professionals jeered Wells from the room “with cries of ‘Humbug’ and ‘Swindler,’” The patient experienced analgesia and amnesia, but the appearance of failure was enough to end Wells’ career as an anesthetist.[2]

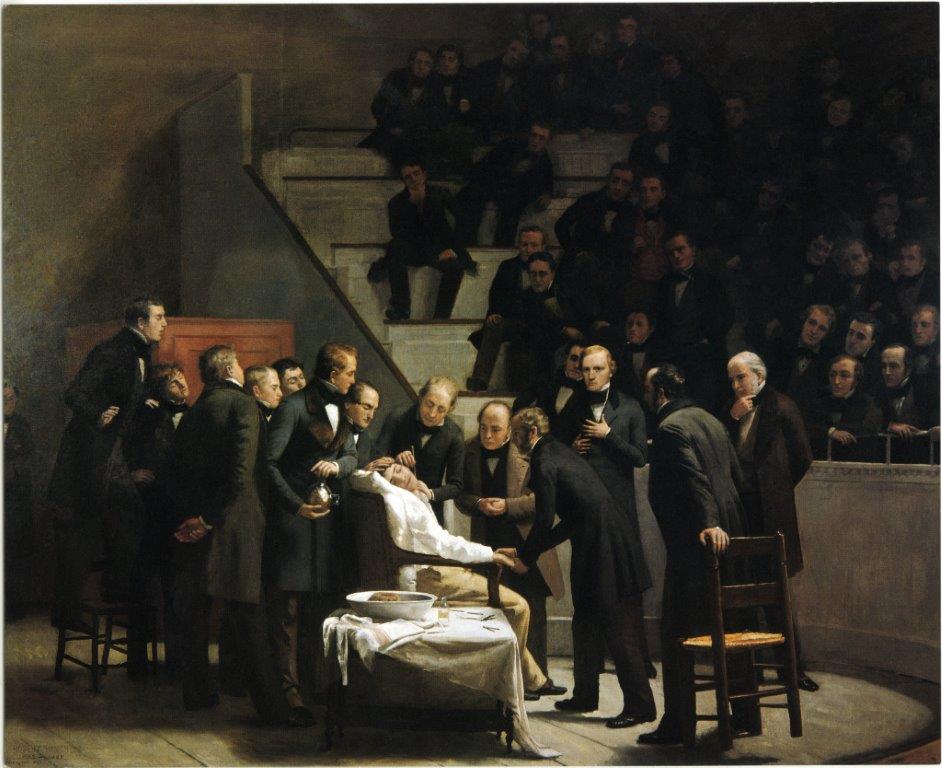

It was an associate of Wells, another dentist named William Thomas Green Morton, that finally brought anesthesia into the mainstream of medical practice. Morton was briefly a student at Harvard Medical School, where he learned about the anesthetic properties of ether.

In October 1846, Morton publicly demonstrated the use of ether as an effective anesthetic at the Massachusetts General Hospital (the same school where Horace Wells had been humiliated). The surgeon Dr. John Warren successfully removed a tumor before an audience of prominent medical professionals. Morton’s demonstration sparked the first general campaign in favor of anesthesia as a safe and efficient means of preventing shock and pain during surgery. Morton would later serve as one of the only dedicated anesthetists of the Civil War. Morton’s help must have been appreciated by the wounded of the Union army where he served in field hospitals at the Battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania.

Ether was the second most popular form of anesthesia in the Civil War. Less than a year after Morton’s successful demonstration of ether, experiments with chloroform were already taking place. Chloroform was independently discovered by three different scientists from the summer of 1832 through January of 1833. In 1847, papers on both sides of the Atlantic extolled the virtues of chloroform over ether, and it quickly became the preferred drug of nineteenth century anesthetists.[3]

“Chloroform was preferred because it had a quicker onset of action, could be used in small volumes, and was nonflammable,” argued Dr. Robert Reilly in his paper “Medical and Surgical Care During the American Civil War.”[4] Documentation from the period bears this out. As early as 1853 a surgeon declared “the use of ether has now been entirely superseded by that of chloroform.” One of the main reasons he gave for this was that “mixtures of ether vapour with atmospheric air are highly explosive and have frequently given rise to frightful accidents.”

US Army surgeon Dr. W.W. Keen had just such an experience in his general hospital after the Battle of Gettysburg. “The only available light was five candles…suddenly the ether flashed afire, the etherizer flung the glass bottle of ether…in one direction and the blazing cone fortunately in another direction. We narrowly escaped a serious conflagration.” An older and wiser Keen, reflecting on the event confessed “I must admit gross thoughtlessness. My only consolation is that the patient suffered no harm.”[5]

Not only was chloroform safer, it was more effective. The authors of the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion examined hundreds of cases of anesthetic use and found that the average amount of chloroform used was eleven drams, or a little less than an ounce and a half. Ether, by contrast, was fifty-one drams, or more than ¾ of a cup. Further, “the average time in which insensibility was induced by chloroform was nine minutes, by ether and chloroform seventeen minutes, and by ether sixteen minutes.”[6] Confederate Surgeon John J.Chisolm, in his Manual of Military Surgery insisted to his surgeons that “in all painful operations, chloroform should be freely administered to produce the desired anesthesia.”[7]

Despite the preference for chloroform, ether continued to be used. The authors of the Medical and Surgical History found that around 14% of all procedures relied on ether, and an additional 9% used an ether and chloroform mix. These numbers represent a division between field and general hospitals. The authors state “chloroform was almost uniformly used” in field hospitals, while “ether was frequently used” in general hospitals far behind the lines. Due to the explosive nature of ether, it was a liability for armies on the move and field hospitals where doctors operated by lamplight.[8] This same dynamic was probably true for Confederate surgeons, though due to shortages they may have been forced to transport ether to the frontlines.

Anesthetics were used in staggering quantities during the conflict. The authors of The Medical and Surgical History tabulated the incidents of anesthetic use among United States forces, and their findings are telling. They found at least 80,000 surgeries performed with some form of anesthesia in the North. Only 254 surgeries were reportedly done without anesthesia in the North. That comes out to a roughly 99.68% of surgeries being performed with general anesthesia by US Army surgeons.[9]

A tiny number were performed by Union doctors who had access to ample supplies of ether and chloroform. This confounding choice is unexplained by the authors of the Medical and Surgical History, who speculated the surgeons may have feared that anesthetics might have induced hemorrhage or pyaemia (blood poisoning) and slowed recovery time.

In other, very rare instances, chloroform wasn’t available. Such was the case for Private James Winchell of the 1st United States Sharpshooters. Wounded in the arm and captured, Private Winchell and hundreds of fellow wounded prisoners were not treated by Confederate doctors. Instead, a single captured Union surgeon and a sole attendant had to perform every operation. Winchell waited for days, during which time his wound festered. Finally, in his words, “about noon July 1st, Surgeon White came to me and said: ‘Young man, are you going to have your arm taken off, or are you going to lie here and let the maggots eat you up.’ I asked if he had any chloroform or quinine or whisky, to which he replied ‘no, and I have no time to dilly-dally with you.[‘]”[10]

Again, these were very rare cases. There were perhaps 125,000 surgeries involving general anesthesia both North and South, giving the operating surgeons unprecedented experience with the procedure. In the second part of this article, I’ll discuss the use of anesthesia by the Confederacy and the methods of application in the period.

This is the first part of a two part series. Click here to read part two.

Learn more from Kyle Dalton, the post’s author

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Endnotes

[1] Peck, R.M., “Wagon-Boss and Mule-Mechanic: Incidents of My Experience and Observations in the Late Civil War,” in The National Tribune, Sep 15, 1904, page 8, via Newspapers.com, accessed March 3, 2020, <https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=14856197>.

[2] Gifford, Emily E., “Horace Wells Discovers Pain-free Dentistry,” ConnecticutHistory.org, December 11, 2015, accessed May 27, 2020, <https://connecticuthistory.org/horace-wells-discovers-pain-free-dentistry/>.

[3] See Simpson, Sir James Young, M.D., “On Chloroform (1847),” transcribed in Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology, 2018, accessed April 20, 2020, <https://soap.org/about-us/soap-history-10-29-18/sir-james-young-simpson-m-d-on-chloroform-november-1847/>.

[4] Reilly, Robert F., M.D., “Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861–1865,” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, Vol. 29, No. 2, April 2016, pages 138–142, via US National Library of Medicine PubMed, accessed March 31, 2020, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4790547/>.

[5] Keen, W.W., M.D., L.L.D., “The Dangers of Ether a an Anaesthetic,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 173, page 835, via Google Books, accessed April 1, 2020, <https://books.google.com/books?id=ObA1AQAAMAAJ>.

[6] Medical and Surgical History, 896.

[7] Chisholm, J. Julian, M.D., A Manual of Military Surgery for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate States, Richmond: West & Johnson, 1861, page 128.

[8] Medical and Surgical History, 887.

[9] Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Volume II, Part III, Washington Printing Office: 1883, page 887-898.

[10] James Winchell, “Wounded and a Prisoner,” appendix to Capt. C.A. Stevens, Berdan’s United States sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865, St. Paul, Minnesota: Price-McGill Company, 1892, page 521, via Internet Archive, accessed February 27, 2020, <https://archive.org/details/berdansunitedsta00stev>.