Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

The Confederacy used anesthesia in many similar ways as the North and held just as much admiration for the practice as their Northern enemies. Confederate medical records were burned with Richmond at the end of the war. We must be careful projecting too much on the South from Northern sources.

In this absence of Southern sources, some historians have argued that Confederate soldiers were more likely to go under the knife without anesthesia due to shortages in the South, but this ignores some key factors.

Firstly, the Confederacy prioritized anesthesia. The military medical consensus on the necessity of anesthetics was cultivated in the antebellum period, and there was effectively no resistance to acquiring, producing, and using them during the war. Dr. Hunter Holmes McGuire later asserted “in the corps to which I was attached, chloroform was given over 28,000 times.”[1] Confederate Surgeon John J. Chisolm claimed to have performed or observed 10,000 surgeries under anesthesia over the course of the Civil War. And that’s just one corps of one army. The Confederacy constructed multiple laboratories for production of chloroform and ether across the South, from Virginia to Texas. In the words of Michael Flannery, Dr. Chisolm’s laboratory in Columbia, South Carolina where he produced ether was considered so important that he “asked for and received the single-largest Confederate warrant for medical supplies, over $850,000, issued on April 13, 1864.”[2] For the cash-strapped Confederacy, even weighing in rampant inflation, that’s a sum that proves the importance of anesthetics to Confederate medical personnel. By comparison, the rebels did not prioritize ambulances or stretchers and made no major effort to build their own.

Another factor in the use of anesthesia in the Confederacy is that very little chloroform is necessary to induce general anesthesia. Only about a shot glass worth of chloroform was necessary on average. And this is presuming that, like the North, the Confederacy was generous in their application. Patients may experience analgesia before muscle relaxation and amnesia. If pressed, a surgeon could strap down or have his assistants pin down a patient and perform a less-than-ideal amputation without causing pain and perhaps even with memory loss.

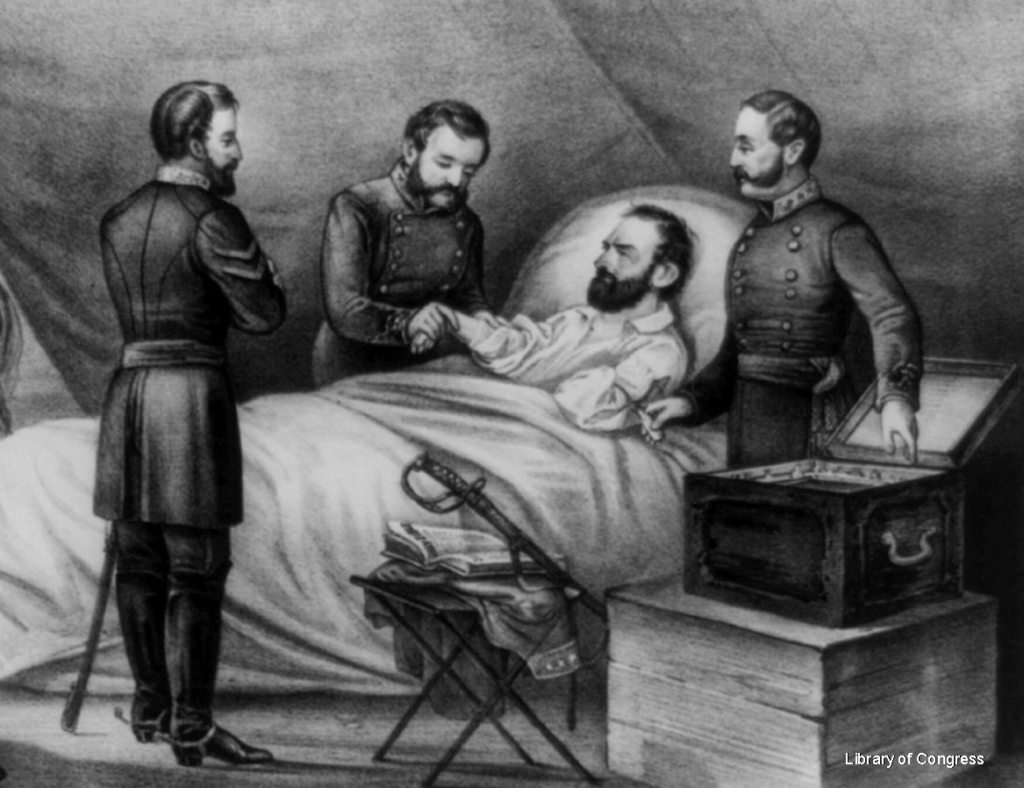

An under-dosage may have been the case for General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. After an infamous friendly fire incident at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Jackson underwent an amputation of his left arm, performed by Dr. McGuire. Jackson’s chief of staff later related the words of the General: “I had enough consciousness to know what was doing; and at one time thought I heard the most delightful music that ever greeted my ears. I believe it was the sawing of the bone.”[3]

Whether he (or any other wounded Confederate) was intentionally under-dosed is speculation.

During the Civil War it was up to the experience to individual surgeons to determine how much anesthesia to give to their patients rather than relying on codified guidelines. It wasn’t until the First World War that “the anesthesia community had the first true systematic approach to monitoring.” In the wake of this destructive conflict, Dr. Arthur Guedel created a system for judging patients’ precise state under anesthesia consisting of four stages.[4] In the first stage patients experience disorientation, in the second they experience “excitement,” while the third is considered the safest for surgery. The fourth stage is overdose, often resulting in death. During the phase of excitement, the patient “may exhibit…muscular movement, phonotation, staring eyes, irregular respiration, etc.”[5] To the untrained eye, it might well appear that an insensible and unconscious patient was under no anesthesia at all.

A further variable was the method by which anesthesia was administered.

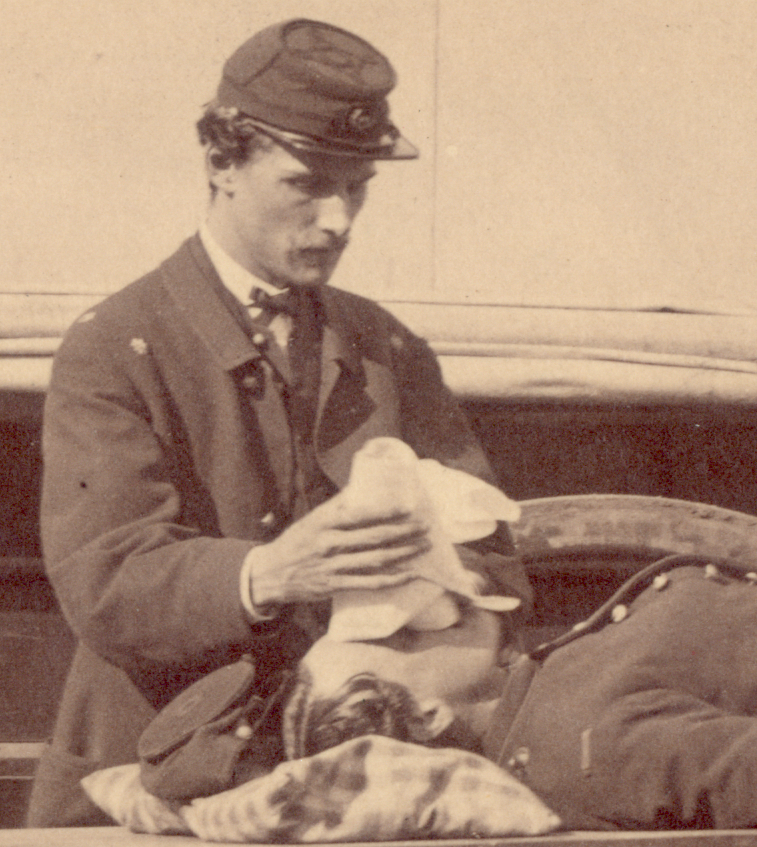

Surgeons of both armies preferred to use a cloth rather than manufactured inhalers. Confederate surgeon Dr. Chisolm related “The best apparatus is a folded cloth in the form of a cone, in the apex of which a small piece of sponge is placed.”[6] Union surgeon Dr. Valentine Mott agreed that “it is best to employ no special apparatus,” but felt that a cloth “in the folded condition…might interfere too much with respiration.” Writing much later, the authors of the Medical and Surgical History stated the folded paper or cloth cone “was the most convenient and common form.”[7] Photographs and artistic representations of field hospitals and amputations, like the one above, universally portray the use of cloth rather than the much heralded metal inhalers developed at the time.

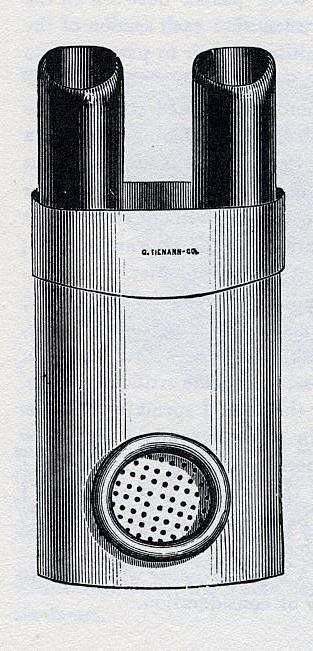

The most famous apparatus invented during the Civil War is the Chisolm inhaler. A pocket-sized applicator with nose pieces that folded neatly into the body of the device, it was probably developed to reduce the use of chloroform in surgery. However, as Bill and Helen Bynum argue in a paper submitted to The Lancet, Chisolm did not invent the device until late in the war, “early examples are rare, and he did not discuss it in the wartime editions of his Manual, nor, apparently, did he try to patent it. All of which suggests that it was not widely used.” The inhaler was displayed in the new Army Medical Museum after the war, and was produced in larger numbers by George Tiemann & Co. for subsequent decades, perhaps contributing to the idea that the device saw more widespread use during the war than it actually did.[8]

In short, the application of anesthetics was inconsistent at times and there was no empirical and uniform guide for how and when to apply it. Nonetheless, over one hundred thousand patients benefited from the innovation in the Civil War, and countless more continue to benefit to this day. I think the final word on this should come from a patient. Dr. Hunter Holmes McGuire related Stonewall Jackson’s words as he drifted into unconsciousness from chloroform. “As he began to feel its effects, and its relief to the pain he was suffering, he exclaimed, ‘What an infinite blessing!’ and continued to repeat the word ‘blessing,’ until he became insensible.”[9]

This is the second post in a two part series. Click here to read part one

Learn more from Kyle Dalton, the post’s author

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Kyle Dalton is a summa cum laude graduate of the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where his paper Active and Efficient: Veterans and the Success of the United States Ambulance Corps was awarded the Zeender Prize for best history thesis. In his spare time Kyle writes and maintains a website on the lives of common sailors in the eighteenth-century: BritishTars.com.

Endnotes

[1] McGuire, Hunter M.D., L.L.D., “Annual Address of the President,” Transactions of the Southern Surgical and Gynecological Association, Volume II, Published by the Assocation, 1887, page 7, via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed March 31, 2020, <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hc>.

[2] Flannery, Michael, Civil War Pharmacy: A History, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 2017, page 205.

[3] Prof. R. L. Dabney, D.D., Life of Lieut. Gen. Thomas J Jackson, (Stonewall Jackson), New York: Blelock & Co., 1866, page 696, via Google Books, accessed February 26, 2020, <https://books.google.com/books?id=h7xcAAAAcAAJ>.

[4] Freeman, Brian S., “Stages and Signs of General Anesthesia,” in Anesthesiology Core Review, McGraw Hill Medical, via Access Anesthesiology, accessed April 1, 2020, <https://accessanesthesiology.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?sectionid=61588520&bookid=974>.

[5] Hewer, C. Langton, “The Stages and Signs of General Anesthesia,” The British Medical Journal, August 7, 1937, page 274, via the US National Library of Medicine’s PubMed, accessed April 1, 2020, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2087073/?page=1>.

[6] Chisolm, John Julian, A Manual of Military Surgery, for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate Army, Richmond: West & Johnson, 1862, page 423, via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed June 4, 2020, <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001586484>.

[7] Valentine Mott, M.D., Pain and Anæsthetics: An Essay, Prepared by Request of the Sanitary Commission, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1862, page 12, via Google Books, accessed February 26, 2020, <https://books.google.com/books?id=ZJjKChJ9LIEC>.

[8] Bynum, Bill, and Bynum, Helen, “Chisolm Chloroform Inhaler,” The Lancet, Vol. 387, Issue 10035, June 4, 2016, accessed April 1, 2020, <https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(16)30693-6/fulltext>.

[9] McGuire, Hunter, M.D. “Last Wound of the Late Gen. Jackson (Stonewall),” Richmond Medical Journal, Vol. 1, May 1866, pages 403-412, Harvard University via HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed March 31, 2020, <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044102974508>.