Table of Contents

During the Civil War, the United States Army discovered the importance of veterinary medicine by trial and error. It’s a history of ethics and economics, of sacrifice and of stupidity.

Before the Civil War, any organized veterinary corps in the United States was at best an experiment, often a whim. Let’s start at the very beginning: the American Revolution. On December 16th, 1776: General George Washington issued an order, ruling that a farrier (an expert in good animal care) be included in the roster for each new regiment. Each farrier had practical knowledge about the treatment of horses and was responsible for medical care required by cavalry horses. These farriers were the first veterinarians in the U.S. Army.

Until the Civil War, there was only one veterinarian who served in the United States military who had a post-secondary degree in Veterinary Science—and he served in the Revolutionary War. That means that during the Northwest Indian War, the War of 1812, the Second Seminole War, and the Mexican-American War, there wasn’t a single degree-holding veterinarian in the Army, Navy, or the Marines to treat horses, mules, and other animals essential to army operation. During this time period, it is unclear how many, if any, soldiers were dedicated to caring for military animals. For example, although 1830s Army regulations called for “veterinary surgeons” and a “Veterinary Department of the Cavalry,” there’s no evidence any such persons existed. Most reports instead show commanders contracting with private veterinarians to treat their horses.

It’s unlikely these private, civilian veterinarians would have been well-trained. In fact, in 1847, there were only 15 trained veterinarians in the United States. The other, untrained, veterinarians were known as “horse doctors.” They were businessmen lacking formalized veterinarian training and working with only the experience they got on the job. Some were good doctors, many were not.

This began to change in the 1850s. Many in the civilian world began to realize the dire need for animal health expertise in their communities. Several medical colleges introduced lectures on animal medicine. There were more than 25 attempts to start veterinary schools of medicine in North America in the decade before the Civil War. However, veterinary medicine still had a long way to go; most of the 25 veterinary schools quickly floundered and failed.

Meanwhile, members of the U.S. Army were facing similar struggles while fighting to make a place for veterinarians in the ranks. In 1853, Quartermaster General Thomas S. Jesup appealed to Congress to establish an Army Veterinary Corps and create a school to instruct Army veterinarians. His request was denied.

A young George B. McClellan, the man who would go on to lead the Union Army during the early years of the Civil War, advised his superiors that “to staff each mounted regiment there should be added a chief veterinary with rank of Sgt. Major, or even a commissioned officer” and that there should also be an Army veterinary school. While observing the Crimean War in Europe, McClellan saw the need for educated animal doctors. However, the Army ignored McClellan’s advice.

The lack of Army veterinarians did not mean that there was a lack of army animals. On the contrary, while the U.S. Army refused to invest in veterinarians, they were putting resources toward experiments to find the ideal military mammal, especially as fighting moved westward. In 1855, the U.S. Army began testing camels for use as pack animals instead of horses or mules. One soldier reported he’d rather have one camel than four mules. However, before the Army could invest heavily in camels, the American Civil War broke out. Sadly for the project, the man who spearheaded the experiment while Secretary of War in the 1850s, Jefferson Davis, also led the Southern states in rebellion against the United States government. Thus, the Camel Corps was dissolved.

Not only was there no Camel Corps at the beginning of the Civil War, there was no formal veterinary corps in the Union or the Confederate armies. There were only fifty veterinarians in the whole United States who held a degree in Veterinary Science, all of whom had studied abroad to get that degree.

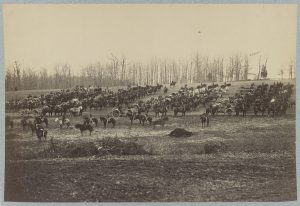

It only took a few battles for the United States Army to realize the significance of a veterinary staff. During the first year of the conflict, the U.S. Army officially formed a veterinary service. Just like Revolutionary forces, each regimental company was ordered to have one farrier to care for horses and pack animals. Additionally, the position of “Veterinary Sergeant” was created. Each Veterinary Sergeant was responsible for three battalions of horses. These men received the pay and privileges of a non-commissioned officer: $17 a month along with rations, fuel, quarters and a horse.

While the mere existence of military veterinarians may seem like a huge step forward, it was riddled with problems. The most significant issue: there were no set qualifications to be a Veterinary Sergeant. Formally educated veterinarians rarely applied for the position of “Veterinary Sergeant,” and when they did they generally did not get the position. Why reject trained veterinarians? Their diagnoses often took animals out of commission … either to rest or be put down. Officers weren’t pleased with losing their animals, and didn’t realize that veterinarians were often sacrificing a few to protect the many.

Some battalions simply didn’t recognize the position of “Veterinary Sergeant” at all, with disastrous effects. On one occasion, a Union regiment received a number of new horses in poor health. Lacking a veterinarian or farrier, the regiment’s officers selected five regular soldiers to care for the horses. He gave them a horse medicine chest and a copy of a 1783 book entitled Every Man His Own Horse Doctor, then wished them luck. The men improvised without the ingredients for the remedies in their book, concocting medications out of arsenic, water, and flour. Soon, half the new horses were dead, and the soldiers had been removed from horse-duty.

Even when a regiment had a veterinarian on staff, officers often ignored their diagnoses and directions. One veterinarian diagnosed many of his regiment’s horses with glanders, a painful, deadly, and highly contagious upper-respiratory disorder. He ordered that the diseased horses should be euthanized to protect the health of the other animals. The Union Army, in turn, fired him for his prudence. The regiment subsequently hired a horse doctor without who claimed “there was no glanders in the whole army.” Instead, he diagnosed the horses with a far less-serious upper-respiratory illness: distemper, and concluded they would recover in a few days. When the Union Army sent the horses out for auction, a trained veterinarian who examined the horses at the auction site confirmed that they indeed had glanders. By ignoring the trained veterinarian’s advice, the Union Army had exposed more animals to the highly contagious disease.

During the early stages of the Civil War, the Union Army’s refusal to invest in veterinarians proved continually detrimental to the health of its animals.

As the war progressed, conditions slowly improved. In 1863, the United States War Department ordered that each cavalry regiment have a “Veterinary Surgeon.” At $75 per month, these men enjoyed more than four times the pay the “Veterinary Sergeants” had received. However, the War Department failed to provide qualifications or instructions for selecting “Veterinary Surgeons,” leaving the responsibility of recruiting these veterinarians to the regimental commanders, with unsatisfactory results.

The Union Army’s Quartermaster Department grew increasingly frustrated with the widespread inefficiency and waste caused by unnecessary animal casualties. One official Quartermaster document fumed that animals which could have been kept in serviceable condition died due to “neglect and imbecility on the part of those in charge.”

Like their counterparts to the North, the Confederacy also failed to care properly for their horses. The Confederate system relied on individual care for horses, rather than governmental or army care. Confederate cavalrymen were responsible for supplying their own mount (horse) and caring for it. The owner received 40 cents from the government per day and full reimbursement if the horse died. When their horses died, Confederate soldiers were responsible with finding their replacements. Men could be gone for weeks, even months attempting to find replacement mounts. The situation worsened when Union forces systematically cut off Confederate access to western states where the majority of the horses were bred. There were no officially sanctioned Confederate Army veterinarians. While the Union may have given their soldiers a copy of Every Man His Own Horse Doctor, the Confederacy expected every man to be one.

As the war progressed, the demand for food for horses quickly became more than the Confederate government could afford. In the winter and spring of 1863 Union horses received a daily ration of 26 pounds of food per day. In comparison, General Lee reported that some days Confederate horses only had a pound of corn and some days they received none at all.

By the end of the war, more than 1.2 million horses and mules had died. In death, many animals received more respect than they did while they were serving in the armies. After the war, the Secretary of War reached out to the Quartermaster General, requesting that farmers be permitted to dig up the bones of fallen military horses and mules in order to use those bones as fertilizer. The Quartermaster declined the request, stating that the animals died in service to their country and their remains should be honored.

Thus the spotty record Army animal care during the Civil War drew to a close. Peacetime was gentler for Army animals. It was not until the Spanish-American War in 1898 that the Army devoted serious thought to further standardizing and improving the veterinarian system.

Learn more about the role of animals in the Civil War with Museum docent Brad Stone

About the Authors

Katie Reichard is the Reservation Coordinator for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. She, arguably, has the best dog in the world.

Amelia Grabowski is the former Education and Digital Outreach Specialist at the NMCWM and the CBMSO Museum. She has a Master’s Degree in Public Humanities and Cultural Heritage from Brown University, where she received the Master’s Award for Engaged Citizenship and Community Service. Amelia has worked for the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, the Bullock Texas State History Museum, humanities councils, and community organizations: all endeavoring to connect the past to the present in engaging and creative ways.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.