Table of Contents

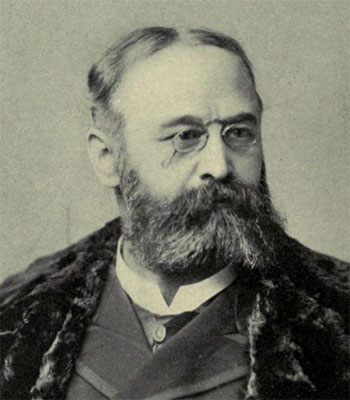

Benjamin Douglas Howard was born March 21, 1836 in Chesham, England, the fourth of five children. His mother died when the children were very young, and soon after his father passed. Howard and his younger brother Ephraim were then placed in the household of a Mr. S. Stone and Mrs. Birch. When Howard finished school, he moved twenty-six miles northeast to the town of Luton where he earned a living as a painter and wallpaper hanger.

In 1853 he immigrated to America and two years later attended Williams College in Massachusetts with the intent of becoming a medical missionary. His classmate at the time, Joseph D. Bartley, later wrote of Howard: “though about the average age of his classmates, gave the impression of greater age and maturity. There was a certain quiet, dignity, modesty, self-possession, and moral earnestness that at once won our respect.” [1]

However, Howard ended up dropping out of Williams College for an unknown reason and moved to New York. He then enrolled in the College of Physicians and Surgeons (now the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons) and received his degree in medicine in 1858. Still wishing to become a medical missionary, Howard enrolled in the Auburn Theological Seminary but later dropped out due to ill health.

After reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the early 1850s, Howard decided to gain a working knowledge of the institution of slavery. He secured a job as a clerk in a slave market in St. Louis, Missouri, where he witnessed the horrors of the slave trade firsthand. He became an active participant in the Underground Railroad, helping slaves escape north to Canada. However, his rouse was discovered, and he fled Missouri.

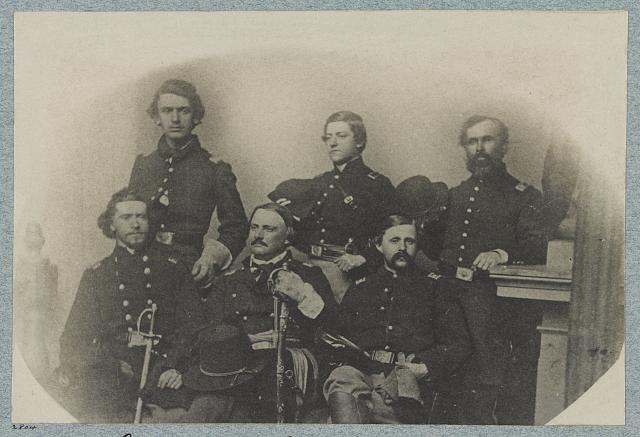

When the Civil War erupted, Howard volunteered his services as a surgeon, and was mustered into service May 22, 1861 as assistant surgeon in the Nineteenth Regiment of New York Volunteers, later known as the Third New York Light Artillery. He was appointed on August 28, 1861 as assistant surgeon in the regular army and became attached to the Army of the Potomac serving on the staff of Major General George McClellan.

In September 1862, the Army of Northern Virginia led by General Robert E. Lee crossed into Maryland. The Union and Confederate armies clashed on South Mountain on the 14th and then on the banks of the Antietam Creek three days later. Howard found himself at Philip and Elizabeth Pry’s house under the direction of Major Jonathan Letterman, the Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac. The Pry House served as headquarters for both Dr. Letterman as well as McClellan and his staff.

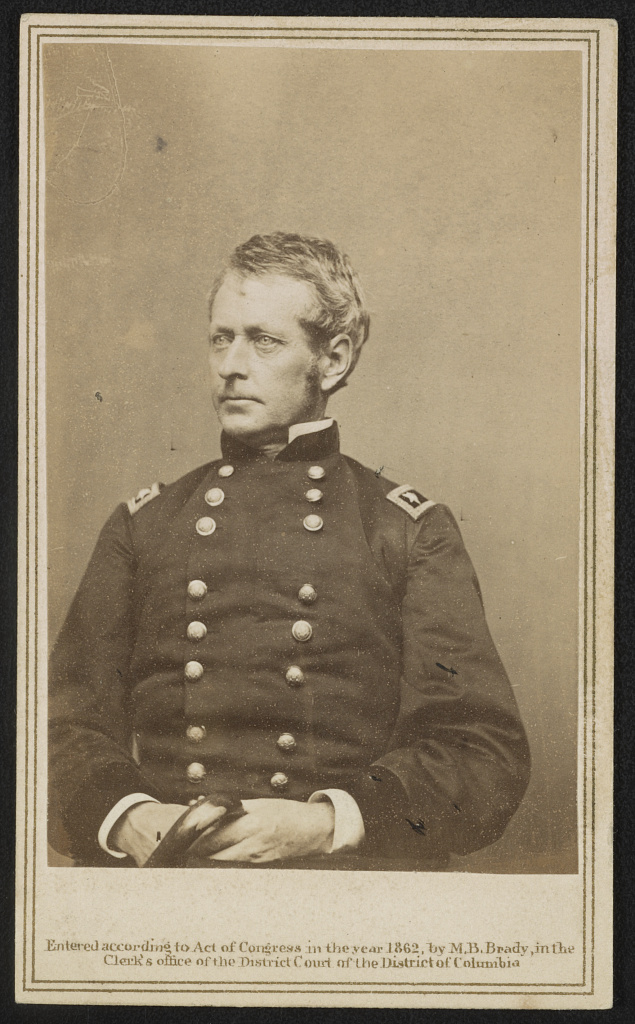

As the Battle of Antietam raged, Howard provided valuable aide to Union Medical Director Dr. Jonathan Letterman, riding all over the field and reporting back the condition of the Medical Department.[2] In the chaos of battle that day, Howard returned to the Pry House and tended to Major General Israel Richardson, who had been mortally wounded at Bloody Lane and was taken to an upstairs bedroom. Howard, at the behest of McClellan, examined the injured general along with Dr. Letterman and both men decided the wound was fatal. Richardson, suspecting the worst, asked the doctors what his chances of survival were. Both told him “one in twenty.”[3] They also pressed Richardson’s division doctor, and close friend, Dr. Taylor to tell Richardson he would not live. Taylor refused, saying if he did so, it would kill Richardson. [4] While Richardson did begin to recover, infection set in and he died in the Pry House on November 3, 1862.

Major General Joseph Hooker was also taken to the Pry House for treatment following his injury at Miller’s Cornfield. He had been on his horse, standing up in the stirrups, when a mini ball passed through the bottom of his right foot. Miraculously, the bones were uninjured. Howard examined Hooker’s wound the morning of September 18th at the Pry House, where he cleaned the wound with warm water using a syringe and wrapped it in a cold-water dressing. The following day, Howard found the general very comfortable and the swelling completely gone. He then administered a lotion of plumbi in place of the cold-water dressings. Lotion of plumbi contained lead salts, possibly lead iodine, and was an effective sedative administered to help ease pain. Months later when Howard examined Hooker’s wound, he found “although the step had not its former elasticity, the wound had left no serious inconvenience behind.”[5]

Following the Battle of Antietam, Howard served as medical purveyor and acting medical director of the Department of the Ohio. On June 25, 1863, he sent a letter to Surgeon General William Hammond recommending a new mode of treatment for penetrating wounds of the chest and abdomen by hermetically sealing it. His recommended method of treatment included applying layers of collodion to threads of linen to create an airtight seal around the wound, allowing the lungs to expand freely (a treatment style used today with sucking chest wounds).

While Howard believed this treatment would drastically reduce the mortality rate of these types of injuries, studies published in The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion found no evidence of this. The problem with Howard’s recommendation was likely twofold: first, physicians at the time had no working knowledge of the physiology of these wounds (most wounds to the trunk of the body were usually considered mortal) and second, with germ theory still years away, the true cause of infection was unknown.[6]

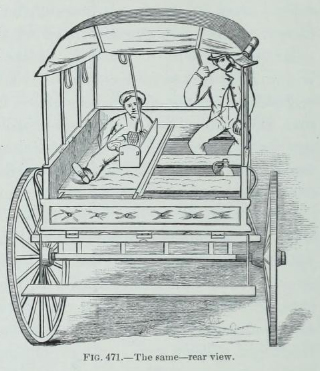

In October 1864, Howard developed a new ambulance for field use that implemented rollers for the loading and unloading of litters, semi-elliptical springs that allowed for a much smoother ride, adjustable internal springs and cushioned seats. Two prototypes were placed in each division and were evaluated over nine months.

Weighing 1,232 pounds, the Howard Ambulance was found to be heavy and cumbersome, requiring four horses to pull instead of two and ceased to function if the special litters were lost. Union Surgeon T.R. Spencer reported, “The only advantage it seems to possess is in the greater convenience in loading and unloading”[7] while Union Surgeon Charles Page noted, “[f]or marches I think the Howard ambulance wagon is superior; but for field work, in time of action, I would prefer the present Rucker pattern of ambulance wagon.”[8] While it never saw widespread use during the Civil War, Howard’s ambulance did find widespread use in the French Army in the 1870s.

Howard resigned the military on December 28, 1864 and moved to New York where he practiced medicine and specialized in surgery. In 1871 he published a prize-winning essay for the American Medical Association entitled The Direct Method of Artificial Respiration, or the Treatment of Persons Apparently Dead from Suffocation by Drowning or from Other Cause. It became known as Howard’s Direct Method of artificial respiration and was adoptedand used throughout the United States. Around 1873, Howard returned to England and helped establish the London Ambulance Service.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Howard studied prison systems throughout the world and in 1888 traveled extensively visiting prisons in the United States, England, Germany, Russia and Siberia. He wrote two books on the subject, Life with Trans-Siberian Savages printed in 1893 and Prisoners of Russia: A Personal Study of Convict Life in Sakhalin and Siberia printed posthumously in 1902. Howard returned to New York in 1896 with failing health and died on June 27, 1900 from liver disease in Elberon, New Jersey where he was buried.

Although Howard never fulfilled his dream of becoming a medical missionary, he did make significant contributions throughout his life. His method for treating sucking chest wounds during the Civil War, though largely unsuccessful at the time, is still utilized today and another example of the lasting innovations of medicine during the Civil War. His work founding the London Ambulance Service, his method of artificial respiration and support of the Underground Railroad all prove Howard worked tirelessly to improve the lives of those around him for generations to come.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Endnotes

[1] Benjamin Howard, Prisoners of Russia: A Personal Study of Convict Life in Sakhalin and Siberia (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1902), vii, https://archive.org/details/prisonersofrussi00howarich/page/n7.

[2] Jonathan Letterman, Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1866), 40.

[3] Gary Scott, Historic Structures Report. The Philip Pry House. Headquarters of Major General George B. McClellan. Antietam National Battlefield, ed. Donald Pfanz. (Sharpsburg, MD: Antietam National Battlefield Site. National Park Service. Library Copy), 35.

[4] Ibid.

[5] George A. Otis and D.L. Huntington, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion Part III Vol II (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883), 60, https://archive.org/details/MSHWRSurgical3/page/n73.

[6] https://www.healthline.com/health/sucking-chest-wound.

[7] George A. Otis and D.L. Huntington, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion Part III, Volume II (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883), 953-954, https://archive.org/details/b21504015_005/page/954.

[8] Ibid, 953 – 954.

About the Author

Rachel Moses is the Site Manager for the Pry House Field Hospital Museum. She received her M.A. in History and Museum Studies from Youngstown State University in Ohio. She most recently worked as an Education Specialist for the West Virginia State Museum in Charleston, WV from 2011 to 2018.