Table of Contents

In antebellum America, nothing was more celebrated in popular discourse than the role of mothers. In the nineteenth-century equivalent of the “mommy blog,” ladies’ magazine ran articles that extolled the moral virtues of the large family, the daily and weekly routines of housework and childcare, and the responsibilities of True Womanhood. “How entire and perfect is this dominion over the unformed character of your infant” crowed Ladies Magazine to its female readers in 1838. Writer and abolitionist Lydia Maria Child declared that it was mothers “on whose intelligence and discretion the safety and prosperity of our nation so much depend.”[1]

But for all the praise heaped on Civil War-era women for their roles as mothers, they also spent an awful lot of time trying to not become one.

At first, the phrase “nineteenth-century birth control” may seem like an oxymoron. After all, “the Pill” wasn’t invented until the 1950s and not approved for use in the United States until 1960. And even then, it was still illegal. It’s only in the past thirty years or so that American women and their partners have such a wide choice in safe, legal contraceptive technologies. But as the present controversies over reproductive technology show no sign of abating, it’s worth taking a look back to see where we’ve come from to help frame and contextualize these debates going forward.

And rest assured – Victorian Americans, like us, spent a lot of time thinking about how to not get pregnant.

As one editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association put it later in the nineteenth century, “We do not exaggerate: everyone that knows anything of American society in cities (at least) knows that there are very few married people that do not or have not discussed methods of preventing conception, and the majority of physicians will have no difficulty in remembering instances in which they have been consulted on this subject.”[2]

Despite the fact that religious, medical, and political organizations issued dire warnings to the public on the moral and physical dangers of contraceptives and abortion, the nineteenth century American public stubbornly insisted on implementing family planning methods – and in ways that were widespread enough to have both a significant impact on the population and on the public conversations surrounding the morality and social value of birth control.

In 1800, the birth rate in the United States was the highest in the world, with the average women bearing eight children. But by the end of the nineteenth century, women were bearing, on average, only three.[3] As birth control historian Linda Gordon has observed, this drop in family size occurred despite the fact that state legislatures beginning in the 1840s banned the sale and use of contraceptives (culminating in the federal ban via the Comstock Law of 1873), and that abortion was criminalized in every state by 1880.[4]

In an era long before chemical or hormonal contraceptive technology, Civil War-era Americans used the same methods known for centuries throughout the early modern world to prevent pregnancy. These, of course, included the ancient methods of coitus interruptus—or withdrawal, and the rhythm method. But there was also an active nineteenth-century market for birth control devices, including vaginal suppositories or pessaries (which physically blocked the cervix), syringes sold with acidic solutions for douching, and antiseptic spermicides. Condoms were also relatively popular, especially after mid-century when new techniques made it easier to manufacture rubber and their price dropped significantly.

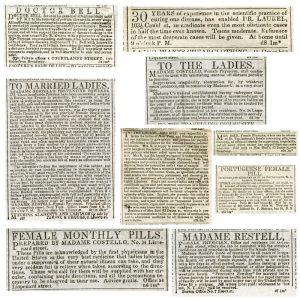

The contraceptive market advertised these devices both openly (often flouting local and state laws) and with coded language, using phrases like “feminine hygiene,” “female wash,” “female tonic,” “female remedies,” “female pills,” “prevention powders,” “regulators,” “disinfectant”, and my personal favorite — “Mother’s friend.”

Abortions were also readily included in the universe of Civil War era birth control. Though the practice was never without controversy, abortion was legal in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries until the moment of “quickening,” when the pregnant woman could feel fetal movement. While exact statistics are difficult to calculate, we do know that abortion rates rose steadily between 1830-1860, to one in five pregnancies.[5] The most common means included the women’s ingestion of abortifacient drugs, as well as abortions performed with surgical instruments by trained practitioners (who weren’t always physicians). One of the most famous abortion providers in the country was Madame Restell, who ran a thriving business for over three decades in New York City, and had satellite offices in Boston and Philadelphia.

The kind of woman most likely to avail herself of an abortion provider was white, native-born, Protestant, and middle-class.[6] The anxieties produced over this segment of the population’s “visible use of abortion” as historian Leslie Reagan has phrased it, eventually galvanized the newly emergent American Medical Association to campaign to make abortion at every stage of pregnancy illegal. Their crusade not only succeeded, but also cemented the prestige and importance of the medical profession in American life, and established the physician as the leading authority on women’s health.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Footnotes

[1]Cited in Nancy Woloch, ed., Women and the American Experience, 4th edition (McGraw-Hill, 1994), 120.

[2] “The Ethics of Marriage,” The Journal of the American Medical Association, Sept 1, 1888.

[3]Linda Gordon, The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America (University of Illinois Press, 2002), 23.

[4] Leslie J. Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867-1973 (University of California Press, 1997), 4.

[5] Andrea Tone, ed., Controlling Reproduction: An American History (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1996), 100.

[6] Reagan, 9

About the Author

Dr. Lauren MacIvor Thompson is a Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Kennesaw State University and a Visiting Fellow in the Georgia State University College of Law. She earned her Ph.D. from GSU in May 2016. Her research centers on the forces of law and medicine, and their role in the early history of birth control. She has a background in Public History and before returning for her doctorate, worked for various history museums and state agencies on historic garden preservation, public history projects, and Section 106 federal and state historic resource protection. She is an editor for the website Nursing Clio.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.