Clara Barton and the Search for Missing Soldiers

Madam:

I have seen my name on a sheet of paper somewhat to my mortification, for I would like to know what I have done, so that I am worthy to have my name blazoned all over the country. If my friends in New York wish to know where I am, let them wait until I see fit to write them. As you are anxious of my welfare, I would say that I am just from New Orleans, discharged, on my way North, but unluckily taken with chills and fever and could proceed no farther for some time at least. I shall remain here a month.

Respectfully, you obt. Servt.

Joseph H. Hitchins

When Clara Barton and her staff at the Missing Soldiers Office received this letter in October 1865, they had already spent seven months spearheading search for thousands of missing Union soldiers. After the Civil War, Clara Barton established the Missing Soldiers Office to search for Union soldiers that never came home. By 1868, more than 40,000 people had written to her, desperate for any news of their missing loved ones. As one mother wrote, “could you by any means give to me any knowledge of the last resting place of my darling one you would confer such a favor as none less desolate than myself can appreciate.” Barton and her staff wrote up to 100 letters a day, responding to requests and seeking information about the missing.

Clara Barton was no stranger to hard work. During the American Civil War, she collected supplies for Union soldiers and traveled to the front, delivering those supplies and assisting in any way she could. Sometimes this simply meant talking to the soldiers, bringing them food and water, or helping them write letters to loved ones at home. As the war progressed, Barton learned first aid on the battlefield. By assisting the doctors, she earned a reputation as a pioneering nurse. In the words of one surgeon, “General McClellan, with all his laurels, sinks into insignificance beside the true heroine of the age, the angel of the battlefield.”

Twenty years later, in 1881, Barton would use everything that she learned on the battlefield to found the American Red Cross. However, in 1865, Barton was working on a different humanitarian project.

As the war came to an end, Barton witnessed the incredible confusion as prisoners of war returned home, unsure of their loved ones’ whereabouts. Similarly, every day, sacs of mail arrived at parole camps from loved ones, hoping against hope that their son, brother, or husband was not dead, but one of the returning prisoners. Barton obtained permission from President Lincoln to assist both the returning soldiers and their loved ones. Stationing herself in Camp Parole, Maryland, she responded to families’ questions, letting them know that “Boats are landing almost daily, and any information which I may gain will be most cheerfully forwarded to you at the earliest moment.”

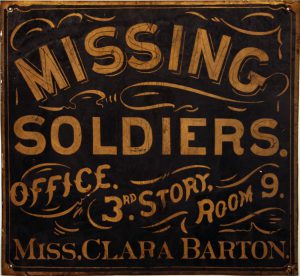

Barton named her operation the “Missing Soldiers Office.” She quickly moved her headquarters to her boarding house home in the heart of Washington, DC, and hired a small staff to assist her. Thousands of women wrote to Barton: hoping for good news or needing official confirmation of the worst in order to claim their widow and orphan pension benefits.

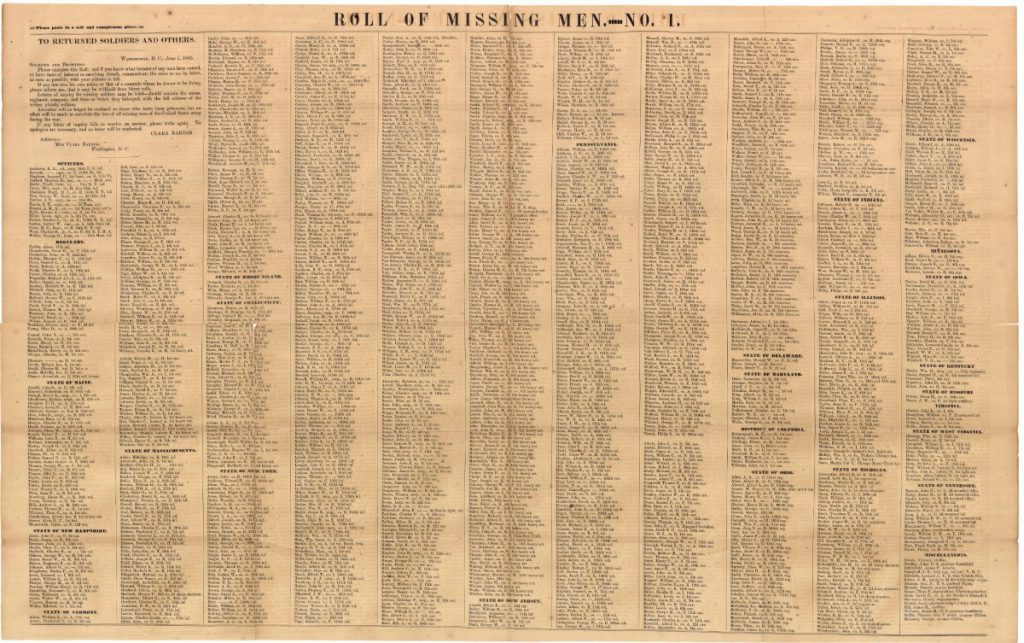

Barton and her staff would send up to a hundred letters a day: responding to initial requests, writing to their contacts in the U.S. Army to inquire about a soldier’s fate, and conveying their discoveries to family and friends of the missing. If the staff of the Missing Soldiers Office could not discover a soldier’s fate through their letter writing campaign, they added his name to a “Roll of Missing Men.” Approximately once a year, Barton and her staff printed this list, sending copies across the United States, imploring anyone with information to write them.

Joseph Hitchins saw his own name on one of these rolls and was outraged. He scrawled an angry letter to Barton, demanding “to know what I have done, so that I am worthy to have my name blazoned all over the country.” Imagine Barton’s reaction—after months of tirelessly searching for missing soldiers, to discover this one, very much alive and hiding from his relatives.

Barton responded to Hitchins letter, giving him a piece of her mind:

The cause of your name having been “blazoned all over the country” was your unnatural concealment from your nearest relatives, and the great distress it caused them. “What you have done” to render this necessary I certainly do not know. It seems to have been the misfortune of your family to think more of you than you did of them, and probably more than you deserve from the manner in which you treat them. They had already waited until a son and brother possessing common humanity would have “seen fit” to write them…. You are mistaken in supposing that I am “anxious for your welfare.” I assure you I have no interest in it, but your accomplished sister, for whom I entertain the deepest respect and sympathy, I shall inform of your existence lest you should not “see fit” to do so yourself.

Barton included one last dig at Hitchins in her signature. Rather than closing with the common send off “I have the honor to be your obedient servant” as Hitchins had, Barton instead signed her reply “I have the honor to be, Sir, Clara Barton.” She was no one’s obedient servant.

Clara Barton continued to operate the Missing Soldiers Office for another three years. By December of 1868, Barton and her team had located over 22,000 missing soldiers, including the very much alive Joseph Hitchins.

Read the complete Hitchins letter exchange here.

About the Author

Amelia Grabowski is the Education and Digital Outreach Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum. She earned her Master’s degree in Public Humanities and Cultural Heritage from Brown University, where she received the Master’s Award for Engaged Citizenship and Community Service. Grabowski has previously worked for the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, the Bullock Texas State History Museum, humanities councils, and various community organizations.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.