Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

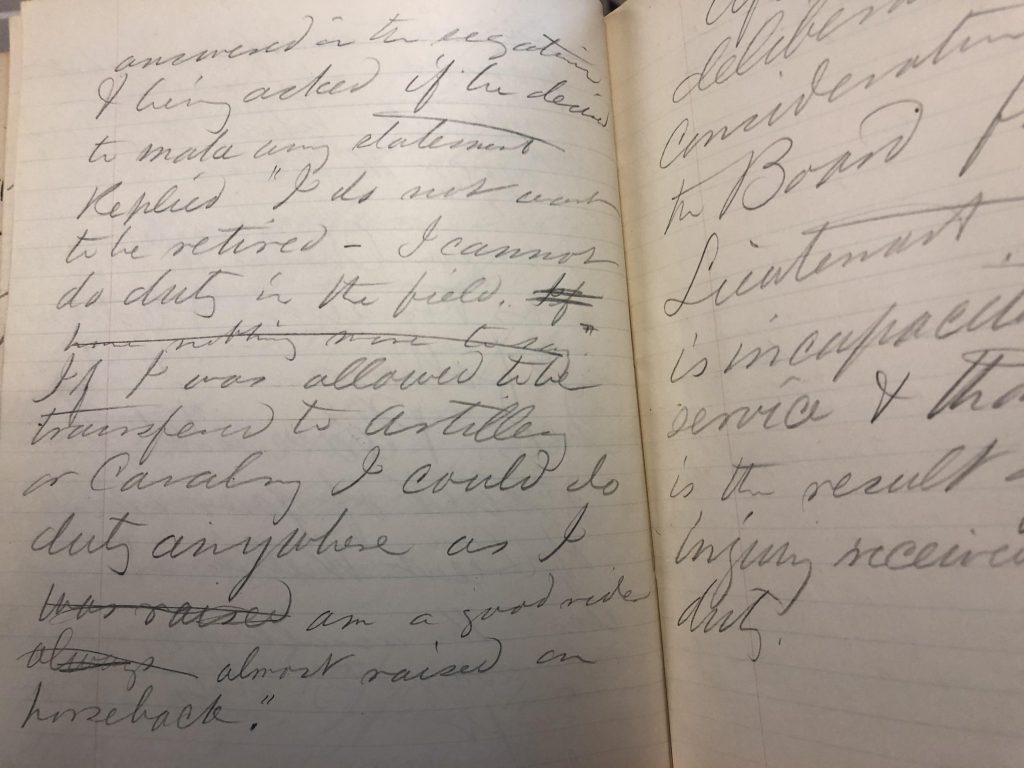

“I do not want to be retired,” pleaded Lieutenant George Williams of the 4th US Infantry on November 4, 1863. “I cannot do duty in the field. If I was allowed to be transferred to the artillery or cavalry, I could do duty anywhere as I am a good rider, almost raised on horseback.” His appeal was to no avail, for shortly after Lieutenant Williams uttered those words, the Board to Retire Disabled Officers delivered their verdict:

“After mature deliberation and a careful consideration of his case, the Board finds that 1st Lt. George Williams of the 4th US Infantry is incapacitated for active service and that his incapacity results from wounds and sickness incurred in the line of his duty.”

The Board to Retire Disabled Officers was established in August 1861 in an effort to reduce the number of older, infirmed regular army officers on active duty as the country entered a war. It was the Board’s job to examine officers to ensure they were medically fit to perform their duties. Some cases derived from wounds suffered in battle. Others were from debilitating conditions or diseases suffered while in military service.

The case of George Williams is one of 19 similar documents contained in the collection of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. The cases cover a time period from September 1863 through May 1864. Though they form a small sample size, they demonstrate the impact doctors had on soldiers serving on the front lines. The word of a surgeon regarding medical fitness could change a soldier’s entire career in the blink of an eye.

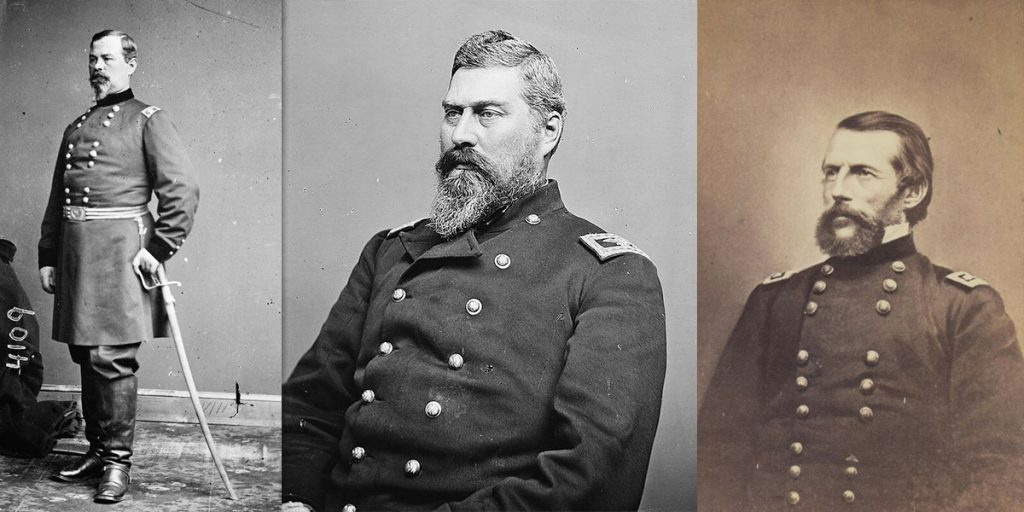

In the latter part of the Civil War, the Board contained generals who had outlived their usefulness on the battlefield, such as Irvin McDowell (of 1st Bull Run infamy) and Erasmus Keyes. In addition to McDowell and Keyes, Colonel Delos B. Sackett (who helped found the Invalid Corps) and a rotating group of surgeons – John Campbell, E.J. Baily, Charles McCormick, Eben Swift, Charles H Lamb, and Charles Sutherland – served on the Board from 1863-1864. The Board convened in Wilmington, Delaware.

The Board only ruled on regular army officers, not the volunteers who made up the majority of officers in Civil War armies. Although officers could request to go before the Board, it took a specific order to send them before the Board. Those orders occasionally came as a surprise to some who felt they were in good health or nearly recovered from previous wounds or disease.

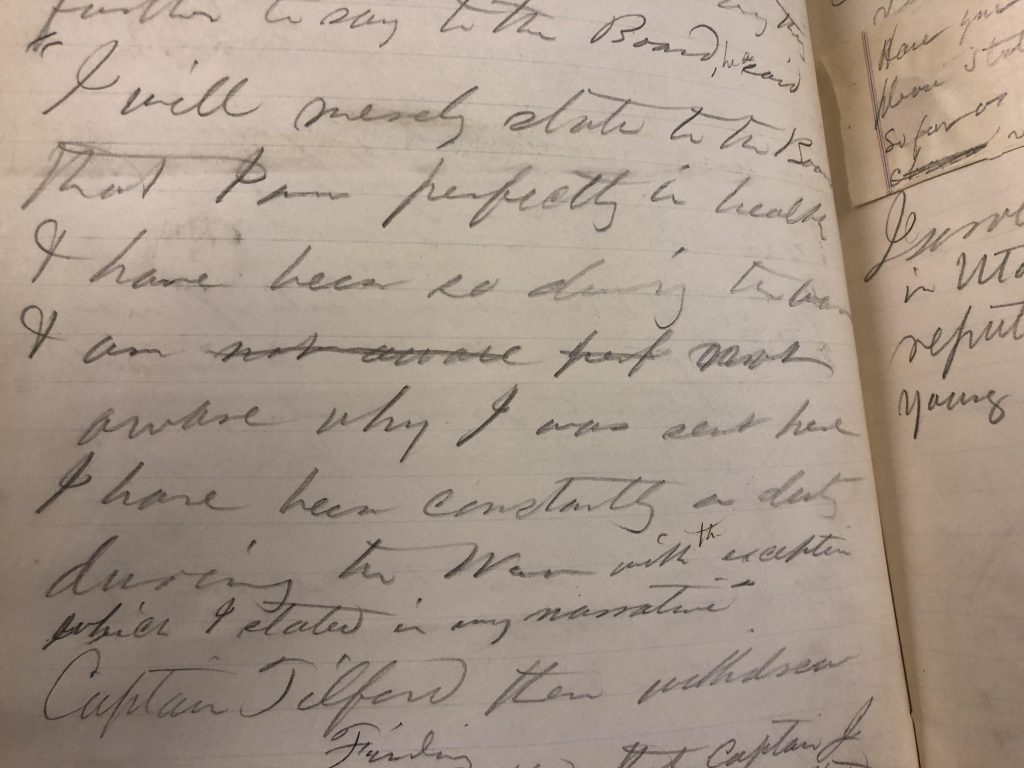

Captain Joseph Tilford of the 3rd US Cavalry represents an officer who experienced a jolt when ordered before the Board. “I am perfectly in health and have been so during the war and am not aware why I was sent here,” he declared before the Board on May 2, 1864. In Tilford’s case, it may be possible someone intended to use the Board to force Tilford out of the army (Tilford was allowed to return to his post).

The hearings all began in similar fashion. Members of the Board asked the officer in question to give a brief statement of their military service. Board members followed up with questions to clarify how a given injury or disease debilitated them.

Subsequently, two surgeons serving on the Board separately examined the men appearing before them to corroborate their stories and give opinions about their fitness for active duty. On this evidence, the Board ruled whether or not the officer was “incapacitated for active service.”

Some of the cases raise eyebrows about what qualified as incapacitated. Major Edward Newby of the 3rd US Cavalry suffered from violent nosebleeds throughout 1862. The Board ultimately ruled him incapacitated for service. Lieutenant Chandler Eakin of the 1st US Artillery, on the other hand, was allowed to keep serving despite an infection in his right eye and open wounds from the Battle of Gettysburg (fought three months before his hearing). Both men insisted they could still serve, but the Board only granted one man a reprieve.

The medical examining board abruptly ended Major Newby’s career because they assessed he wasn’t fit for duty. If Newby himself could have decided, he would have continued to serve. Lieutenant Eakin had an issue that seems at least as debilitating if not more so, but the Board allowed him to continue serving. The examining surgeons deemed the infection in his eye to be mild.

Civil War surgeon’s power to require or prohibit soldiers to serve on the frontlines was felt in other situations too, as in requiring draftees to serve despite their attempts to fabricate medical conditions.

Historian Peter Carmichael speaks to the skewed power dynamic between surgeon and soldier in his book The War for the Common Soldier. “Whether a man was fit to fight or should retire to a field hospital usually came down to the judgement of a doctor.”[1] That decision could mean life or death for a soldier, and it was in someone else’s hands.

It is worth noting an inherent challenge of medical examinations during the nineteenth century. The doctors on the Board had to rely primarily on the patient’s account of their medical history. Surgeons who had examined the patients often said things like “we can judge merely from the history of the case,” revealing limitations on how thorough exams could be.

These cases examining career regular army officers provide an important reminder that several soldiers who served actually preferred being in the army and were not eager to return home. From the evidence in this collection, these officers did not exhibit the typical behavior of a Civil War soldier before a medical examining board. These men were not seeking to procure a medical discharge to leave the service. Faking injuries or disability became common following the institution of the draft in 1863. The men appearing before this Board however, often expressed a desire not to be discharged.

For many, it was the only career they knew. They likely had some concern about finding work outside the army; the unknown presented them with concerning questions. What gainful employment was there outside of the army, especially for one declared medically unfit?

This small and largely forgotten bureaucratic committee forced a number of retiring army officers to confront potentially uncomfortable questions about what would come next for them. To these officers, their hearing before the Board was of tremendous importance to them. If we look closely enough at this set of cases, they highlight the centrality of surgeon’s professional opinions in fielding Civil War armies.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Endnotes

[1] Peter Carmichael, The War for the Common Soldier: How Men Thought, Fought, and Survived in Civil War Armies (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 145.

About the Author

John Lustrea is a member of the Education Department and the Website Manager at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He earned his Master’s degree in Public History from the University of South Carolina. Lustrea has previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park during the summers of 2013-2016.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.