Table of Contents

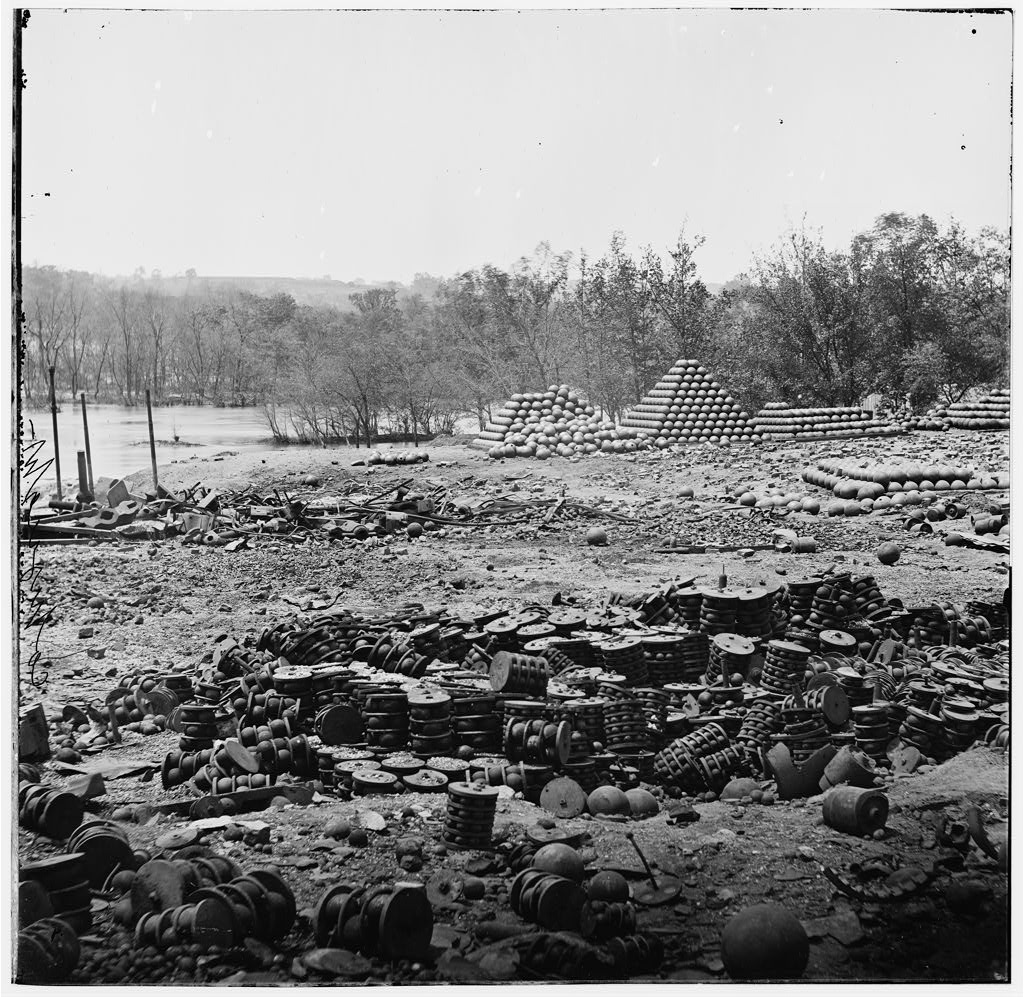

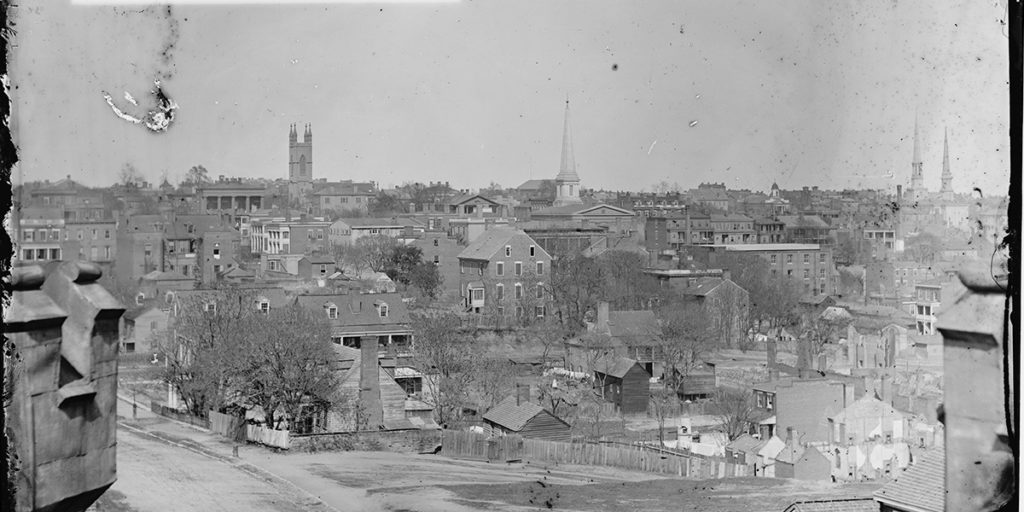

In the center of Richmond, VA the James River flows through the site of numerous wartime industries. One of the most important was the Confederate Laboratory on Brown’s Island. There workers prepared ammunition for the Confederacy’s war effort.

The site employed about 600 workers, of whom half were women and girls. Many of the workers who labored there were German or Irish immigrants, or others who had drifted into the city looking for work. Most made about $1.00 to $2.00 a day, depending on their position and skill.

Captain Wesley N. Smith oversaw the operation, begun in February, 1861. A newspaper article noted that, “Every department is well and carefully heated- Those on the island are rendered comfortable by registers from furnaces …..Very few accidents have occurred at the Lab~ since its establishment- much fewer, indeed, than might reasonably have been expected where so many raw hands have been necessarily employed. The establishment has been of inestimable service, we may say the salvation of the Confederacy. It is the general ordinance manufactory of the South.”

The Laboratory’s workers could produce 200,000 small arms cartridges a day, or about 1,200,000 a week. Those numbers sound impressive, but the army’s need for ammunition was never-ending. For a major battle the Army of Northern Virginia required about five million small arms cartridges and 40,000 rounds of artillery ammunition.

With so many laboring in such a sprawling complex and lacking the modern training and safety guidelines in place today, an accident was bound to happen. On Friday, March 13, 1863, citizens in downtown Richmond heard a large explosion at the waterfront.

In a wooden building one hundred by fifty feet, about sixty workers were laboring when the explosion erupted. Many had gathered that morning to warm up or socialize. In the room some young men were preparing new cartridges, at a table along the wall several teenage girls were breaking open bad rifle cartridges and separating the black powder for reuse. At one corner Mary Cunningham was sewing linen bags for artillery ammunition. Boxes of friction primers and cartridges sat on other tables, and loose powder was scattered on the tables.

None of those activities should have been taking place in the same room, and no one without a need to be in that space should have been there.

At the far end of the room, Irish-born 19-year old Mary Ryan was working with friction primers, small tubes filled with an explosive chemical. Sometimes they stuck in the wooden block which held them, and becoming impatient, workers tapped the block on the table to loosen them.

Irish-born Catherine Cavanaugh, 33 years old at the time, was sweeping the floor, standing directly behind Mary. Across the room, Mary Cunningham saw Mary Ryan banging the friction primers. Then the explosion struck.

Ten were killed instantly, including Alice Johnson, Frances Blassingame, James Curry, among others. The room was “blown into a complete wreck, the roof lifted off, and the walls dashed out, the ruins falling upon the occupants.” Witnesses spoke of “the most heart rendering lamentations and cries . . . from sufferers rendered delirious from suffering and terror.”

As bystanders realized what had occurred, a “tide of people” descended on the island. A single small bridge led from the shore onto the island, and it was soon crowded with people. “Mothers rushed about, throwing themselves upon the corpses of the dead & the persons of the wounded.” Every day for the next eleven days, one of the victims died.

Just up the street, Bailey’s Factory Hospital was a convenient place to bring the wounded. This was a tobacco factory which the military had rented for use as a hospital for soldiers.

It was a three storied, A-roofed building on the south side of Cary Street at the southwest corner of 7th Street. Fortunately, there were only twenty-one patients there at the time – primarily soldiers from Mississippi under the charge of Dr. James M. Holloway – so there was room to accommodate the wounded civilians. As the victims arrived, a reporter noted that they were “all dreadfully burned . . .”

It was not the best facility, and a recent inspection noted, “The building is unsuitable and would have been vacated but for its convenience to the Canal & depots – It has for this reason been the receptacle for the worst cases.”

Unfortunately, we have no details of how the victims were accommodated among the soldiers, or accounts of their treatment. A newspaper account states that “some had an arm or a leg divested of flesh and skin, others were bleeding with wounds received from the falling timbers or in the violent concussions against the floor and ceiling which ensued.” Another article noted that their “burns are serious and several will die.’’

Lacking modern knowledge for burn treatment, those with severe cases likely suffered painfully through their treatment. Many likely had uneven skin regrowth, were scarred for life, had recurring pain, limited range motion, and ultimately faced numerous challenges with resuming regular life.

There were also likely broken bones, cuts, lacerations, concussions, bruises, and powder particles in skin. While they recovered, many victims were interviewed in the hospital or private homes where they rested.

Fourteen-year-old Anne E. Bolton died the afternoon of the explosion, a newspaper article noting that she had “burned to death.” Later that night 15-year old Mary Whitehurst succumbed, “after the severest pains of about 12 hours, caused by the painful accident.”

Josiah Gorgas, chief of Ordnance for the Confederacy, wrote that, “it is terrible to think of it- that so much suffering should arise from causes possibly w/in our control.” His wife Amelia visited the suffering victims, and he noted, “Mamma has been untiring in aiding, visiting & relieving these poor sufferers, and has fatigued herself very much. She has done an infinite deal of good to these poor people.”

There followed an outpouring of relief, much like a modern social media effort. One soldier wrote to a newspaper, “A non resident of the city, I beg to appeal to all humane people in the city & the state, to contribute to so laudable a purpose. The poor wounded creatures are young Females who were dependent on their daily labor for their support. I send you $5 and am only sorry I cannot offer more.”

Arsenal staff donated $2,005, churches joined the effort, as did the mayor and other groups. A theater raised money for their relief, and a ball was held to raise funds.

The day after the explosion, Reverend John Woodcock, who was in the room, and thought to be improving after the accident, passed away. A local newspaper wrote that he was “a most exemplary man in all the relations of life.” Mourners buried Mary Blessingham and Eliza Willis (the youngest victim at 10 years old) in Hollywood Cemetery that afternoon. Sixteen-year old Barbara Jackson also died this day, “after suffering fourteen hours.” The number of dead had grown to 29.

On March 15th Mary Ryan died at the home of her friend Emily Timberlake, who resided within eyesight of Brown’s island. Mary was able to visit with friend Elizabeth Young before she passed away. That same day the city’s churches began collections for the victims, ultimately raising $2,500. On the north side to town, six burials took place in Shockoe Cemetery, all teenage girls who had died in the two days since the accident. The death toll now stood at 36.

The next day a bad snowstorm struck the city, and Mayor Joseph Mayo began to collect aid for the victims’ families. The death toll reached 40.

March 17th was St. Patrick’s Day, and Michael Ryan, Mary’s father, purchased a plot for his daughter in the city’s Hollywood Cemetery.

The next day, 15-year old Robert Chaple died of his injuries. His skull was crushed by the falling debris of the building, and a newspaper recorded that he died “after five days of terrible suffering” “in great agony.”

On March 23, 13-year old Bridget Grimes passed away. A newspaper noted that “During the eleven long days of her excruciating suffering, her priest and physician were untiring in attention.” Her mother Barbara held Bridget’s funeral in their home on 7th Street the next day.

An investigation launched by the military produced a report which concluded, “The opinion of the Board based upon the evidence elicited is that the explosion was caused by the extremely careless handing of Friction Primers by the late Mary Ryan.” By then she had been dead a week.

A total of 64 were killed and wounded, with 50 of those dying. Martha Burley’s body was discovered one month later downstream in the canal near Haxall’s Mill. Ffiteen are known to be buried in Hollywood Cemetery, fourteen in Shockoe Cemetery, and one each in Oakwood and Mount Calvary. The location of the other 20 is unknown.

On April 4th, the Laboratory was repaired and back in operation, and a call went out for 200 girls, but they had to be over age 15. Greater oversight ensured that there was never another accident for the remainder of the war.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Robert M. Dunkerly (Bert) is a historian, award-winning author, and speaker who is actively involved in historic preservation and research. He holds a degree in History from St. Vincent College and a Masters in Historic Preservation from Middle Tennessee State University. He has worked at nine historic sites, written eleven books and over twenty articles. His research includes archaeology, colonial life, military history, and historic commemoration. Dunkerly is currently a Park Ranger at Richmond National Battlefield Park. He has visited over 400 battlefields and over 700 historic sites worldwide. When not reading or writing, he enjoys hiking, camping, and photography.