In every generation there is a chosen one. She alone will stand against the vampires the demons and the forces of darkness. She is the slayer.

Twenty-years ago today, the world heard those words for the first time as Buffy The Vampire Slayer premiered. For those of you who’ve never heard of Buffy, it’s a television show that chronicles the adventures of Buffy, a high school cheerleader, who just happens to be the aforementioned “chosen one”—endowed with supernatural butt-kicking skills (and lovable rare-book reading sidekicks) that enable her to slay vampires and the other demons that haunt her town. But why is a Civil War museum writing about it? Excellent question. As the internet looks back at the beloved show, we invite fans to look back further … at the 1860s history. So many of the elements that make us love Buffy are key components in some of our favorite aspects of Civil War medical history.

(One additional note before I start, it is time for me to confess—I’ve only seen two seasons of Buffy, and a few episodes of Angel. I apologize for any glaring errors that I’ve missed in the latter seasons. I promise to revisit the show on Netflix.)

Kick Butt Women

The show has been celebrated as one of the touchstones of the “Strong Female Lead” genre. Buffy is, in every sense of the word, kick butt. “In the mid-1980s, I’d gotten so tired of slasher film clichés, especially the dumb, oversexed blond stumbling into a dark place to have sex with a boyfriend, only to be killed. I began thinking that I would love to see a scene where a ditsy blond walks into a dark alley, a monster attacks her and she kicks its ass,” explains the show runner Joss Whedon. “So I had this character before I had the idea of using vampires…. I decided to use vampires, because I’ve always thought vampires were cool.”[1]

Civil War women similarly subverted societal expectations of being beautiful, helpless ladies who were there to be fought for and protected, not to fight for themselves. Instead, they joined the battle. They picked fights. All that’s missing are the vampires.

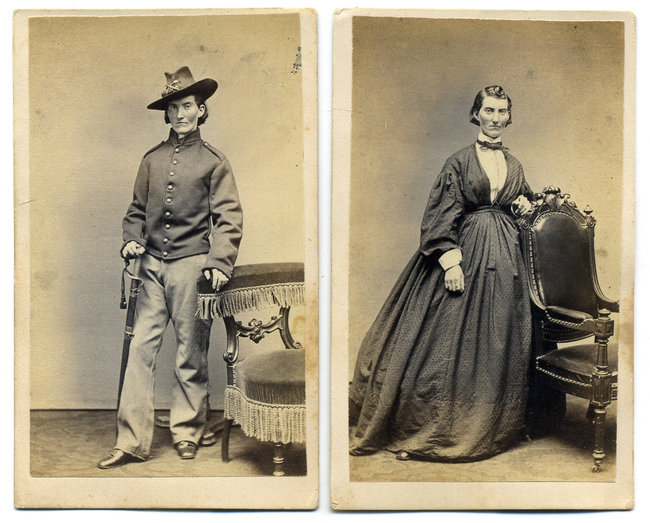

Civil War women were anything but damsels in distress—despite how Hollywood would portray them in the subsequent decades (I’m looking at you D.W. Griffiths). Over 400 women joined the fight … literally. These women disguised themselves as men in order to fight for the causes they believed in, or on occasion to free themselves from problematic and dangerous home situations.

Other Civil War women kicked butt in their own ways. Dorothea Dix staged a one woman war with the United States Army in order to create the first corps of female nurses—thereby introducing nursing as a profession for American women. Countless women volunteered to be nurses—either with the Army, with other humanitarian groups, or independently. These women were risking their own health, and often spending their own money to travel to the front and tend to the wounded.

Dr. Mary Walker was one of the first women in the United States to achieve a medical degree—and she was determined to put it to use. She joined the US Army as a surgeon—the only woman to do so. Much like Buffy, she was undeterred by the gross-ness and goo she faced in the line of duty. She recorded one particularly off-putting case, where “a shell had taken part of [a soldier’s] skull away, about as large a piece as a dollar…I could see the pulsation of the brain, and when he talked I could see a movement of the same, slight though it was.”

Other Civil War women played on societal expectations of their innocence or ignorance in order to spy. Who would expect a society lady, or a lowly slave woman to have the ear of a general? Really, the number of kick-butt Civil War women are too numerous to list, so let’s move on to the next Buffy/Civil-War-med similarity …

The Comebacks

If you’ve watched Buffy, the sass and the comebacks need no introduction.

On the other hand, with a hundred and fifty years of distance, it’s hard to see Civil War figures as sassy, but let me assure you … they were.

My favorite story comes from Clara Barton.

After the war, Barton worked for years to track down missing Union soldiers. One of the ways she found missing men was to publish a list of their names in newspapers across the country, asking anyone with information to write her.

Joseph Hitchins saw his own name on one of these lists and wrote to Barton, indignant. He wanted to know what he had done to have his name “blazoned across the country like a criminal”? If he wanted his sister to know where he was, he would tell her himself. How dare Barton stick her nose in. Barton didn’t take Hitchins’ letter lying down. She wrote him a strongly worded reply, stating “It seems to have been the misfortune of [his] family to think more of you than you did of them, and probably more than you deserve.” Rather than close the letter with the typical signature, “I have the honor to be your obedient servant,” Barton gets in one final burn—writing “I have the honor to be, Sir, Clara Barton.”

The parallels between Buffy and Civil War history don’t stop there (although they do get a bit sillier): Buffy and the gang turn to artifacts to learn more about upcoming apocalypses. At the museum, we turn to artifacts to learn more about … almost everything but apocalypses. We use artifacts to better understand the past and get a new perspective on the present. Another similarity? Buffy and the gang are trying to conserve the blood of Sunnydale residents by protecting them from vampires. Meanwhile, Civil War medics are trying to conserve blood, albeit in a very different way. (I told you the connections got silly.)

The most striking parallel is the amazing, empowered women at the center of both Buffy and Civil War medical history. These are women who don’t take no for an answer, who talk back, and who subvert societal expectations. Just as Joss Whedon challenged society’s preconceived notion of the girl in a horror movie by creating Buffy, I challenge you to second-guess what you think of women in the past. They’re more than secondary characters in intricate costumes. They’re sass-masters, warriors, spies, nurses, and more. They are heroes, and the National Museum of Civil War Medicine is honored to tell their stories.

About the Author

Amelia Grabowski is the Outreach and Education Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum. She has a Master’s Degree in Public Humanities and Cultural Heritage from Brown University, where she received the Master’s Award for Engaged Citizenship and Community Service. Amelia has worked for the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, the Bullock Texas State History Museum, humanities councils, and community organizations: all endeavoring to connect the past to the present in engaging and creative ways. She needs to watch more Buffy.

Footnotes

[1] http://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/buffy-vampire-slayer-turns-20-joss-whedon-looks-back/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.