Table of Contents

Dr. Jonathan Letterman, Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, is a central figure in the story of Civil War Medicine and his innovations in the field are well documented by this institution. Dr. Letterman revolutionized medical evacuation during the Civil War by creating the Ambulance Corps and would influence how doctors and surgeons treated patients for generations to come. In the weeks following the Battle of Gettysburg, located just off of the York Pike, a massive tent hospital named after the Union army’s Medical Director called Camp Letterman was established to care for the flood of wounded soldiers from the battle. After three days of hard fighting in Gettysburg, modern scholarship puts the casualty figures between 51,000 and 52,000 killed, wounded, or missing. According to the American Battlefield Trust, the Union suffered 3,155 killed, 14, 529 wounded, and 5, 365 missing. Confederate figures total 3,903 killed, 18,735 wounded, and 5,425 missing.[1]

The wounded were spread out throughout the small town of Gettysburg following the battle; from George Spangler’s farm to Pennsylvania College at Gettysburg, the wounded were everywhere. The situation was made more complicated when the Union army received orders to move in pursuit of Lee and the remnants of his Army of Northern Virginia. Dr. Letterman left about 100 surgeons and “six ambulances and four wagons per corps when his medical department left with the rest of the army on July 6”[2] as many believed General Meade would reengage the battered Confederates after the defeat at Gettysburg. The patients were spread out and there were not enough surgeons to cover the area. The solution Letterman and his team came up with was the establishment of a central hospital facility in Gettysburg as “800 men a day were being loaded into railroad cars for the trip from various field hospitals to Philadelphia-area hospitals and others in the region.”[3]

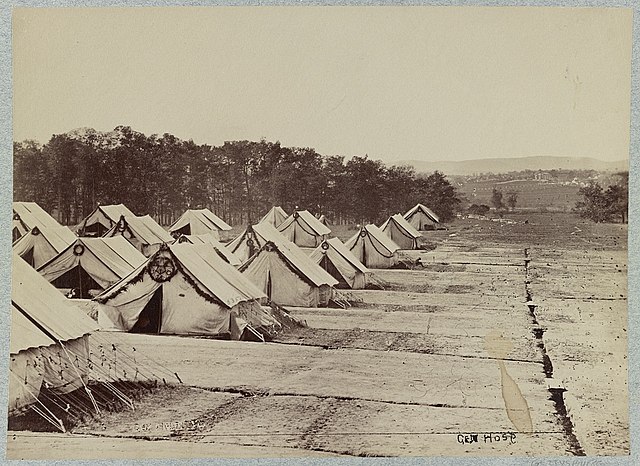

Camp Letterman was placed at what was then the George Wolf farm. It was described “as an advantageous site because of its high ground, abundant spring water, and close proximity to the York Road and Gettysburg Railroad.”[4] The location of Camp Letterman meant that fresh supplies could be acquired or brought in by train while keeping the wounded moving through the system. Hundreds of large hospital tents were constructed hastily due to the increasing necessity of the structures. Construction on Camp Letterman began on July 10 and was completed on July 22. The massive facility included “a dead house, embalming tent, cemetery, cookhouse and warehouse tents.”[5] These additional facilities were needed to supplement the functions of Camp Letterman due to its massive size.

Camp Letterman was used for soldiers who were too sick or wounded to be taken with the rest of the Army of the Potomac on July 6. Depending on the case, if a soldier’s condition were to improve to the point they could be transported, the soldier would be taken to the nearby railroad depot to be transported elsewhere. The most common places Union soldiers would go after recovering enough at Camp Letterman would either be Washington DC, Baltimore, or Philadelphia as those were some of the main hospital hubs in the Union.

The field hospital became “the largest military general hospital built on the battlefield to date…”[6] Doctors, medical assistants, nurses, and patients were being moved to this new facility consisting of several hundred tents with enough space in between to fit a wagon for the wounded. One such nurse who chose to stay in Gettysburg to work at this hospital was Euphemia Goldsboro. She had gained notoriety among the soldiers, mainly Confederates, for her above-and-beyond treatment of Colonel Waller Tazewell Patton of the 7th Virginia (great uncle of General George S. Patton). However, during her tenure at Camp Letterman, she was observed treating both Union and Confederate soldiers with the same level of care and dedication she showed to Colonel Patton.[7]

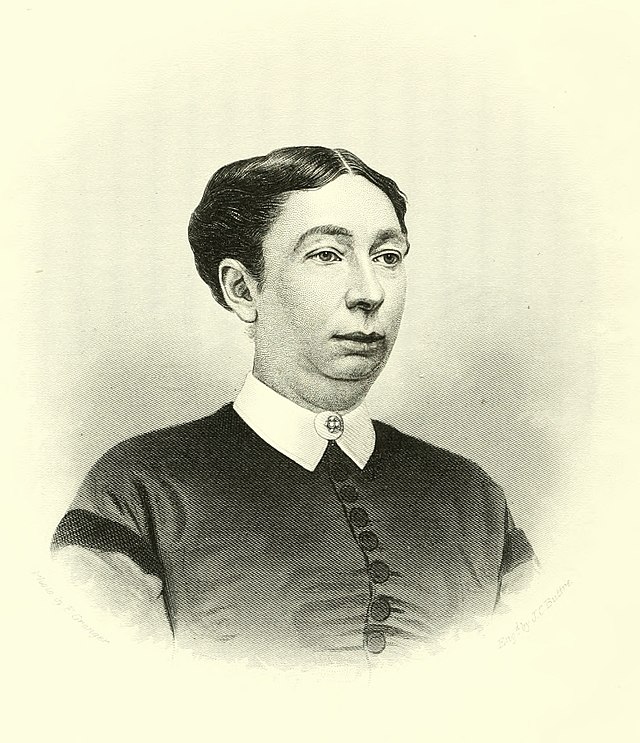

Another nurse serving at Camp Letterman was Sophronia Bucklin, born in Ithaca, New York. Bucklin would write about one soldier under her care at Camp Letterman, “I sat by the bedside of one of Pennsylvania’s noble soldiers, named McMicken, who had lost his leg, and was prostrated nigh to the grave. The surgeon said to him often, ‘Mc. you wouldn’t be here, if it wasn’t for your nurse.’ But we could not save him. He died peacefully one night…”[8] Throughout the Civil War, women would prove themselves as dedicated members of their respective sides through their service as nurses. Women such as Sophronia Bucklin, Euphemia Goldsboro, and more will be remembered by the men they treated in their darkest times.

The medical staff present at Camp Letterman were not able to do everything on their own. Members from the United States Sanitary Commission and Christian Commission, USSC and USCC respectively, volunteered at the hospital, “altogether, 400 men and women of all walks of life worked together at Camp Letterman without jealously or conflict for the benefit of their patients.”[9] Both the USSC and the USCC would operate a post at Camp Letterman until November 10, 1863, just ten days before the camp would be officially taken down.

The hospital remained active until November 20, 1863, the day after Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address to dedicate the National Cemetery nearby. During Camp Letterman’s service, the hospital treated “over 14,000 Union soldiers and 6,800 Confederate soldiers… but more than 1,200 soldiers died because of their wounds, infection, or disease.”[10] Many of the Confederate soldiers who died at Camp Letterman or within the Union hospital system at Gettysburg were returned to the South while many Union soldiers would eventually be buried at the newly dedicated National Cemetery in Gettysburg.

The legacy of Dr. Jonathan Letterman does not just include having a Civil War hospital named after himself, Letterman’s ideas would go on to influence the modern ambulance system and many of his ideas are still being used in hospitals today. Camp Letterman would not be the only medical facility named after the Medical Director. In 1898, Dr. Letterman would have a hospital in San Francisco, his home after the war, named after him due to his achievements in advancing techniques of surgical practices and medical evacuation that are still in use today.

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021.

Endnotes

[1] “Gettysburg.” American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/gettysburg.

[2] McGaugh, Scott. Surgeon in Blue: Jonathan Letterman, the Civil War Doctor Who Pioneered Battlefield Care. New York: Arcade Publishing, 2013. Pg. 194.

[3] McGaugh, Scott. Surgeon in Blue: Jonathan Letterman, the Civil War Doctor Who Pioneered Battlefield Care. New York: Arcade Publishing, 2013. Pg. 194.

[4] “Camp Letterman Historical Marker.” Historical Marker, November 30, 2020. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=133244.

[5] Topping, Elizabeth A. “The USCC at Camp Letterman.” Military Images 39, no. 3 (217) (2021): Pg. 72.

[6] McGaugh, Scott. Surgeon in Blue: Jonathan Letterman, the Civil War Doctor Who Pioneered Battlefield Care. New York: Arcade Publishing, 2013. Pg. 195.

[7] Berger, Stephanie. “Euphemia Mary Goldsboro Wilson (1836 – 1896).” Euphemia Mary Goldsborough Willson , MSA SC 3520-13597, 2009. https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013500/013597/html/13597bio.html.

[8] Bucklin, Sophronia E. In Hospital and Camp. Philadelphia: John E. Potter and Co., 1869.

[9] Topping, Elizabeth A. “The USCC at Camp Letterman.” Military Images 39, no. 3 (217) (2021): Pg. 73.

[10] Backus, Paige Gibbons. “Camp Letterman at Gettysburg.” American Battlefield Trust, January 11, 2022. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/camp-letterman-gettysburg.