Table of Contents

Even prior to joining the ranks of the Union army, Samuel M. Drew’s life had been one of adventure. Born on October 28, 1828 in Cornwall, England, Drew made his way to the United States at age 15 and trained to become a blacksmith. He came to call Northeastern Pennsylvania home and eventually became an early settler in Scranton in 1855.[i] It would not be long before Drew was on the move again, only this time he would don a Union uniform.

At the breakout of the Civil War Drew remained in Scranton but by 1863, he could sit on the sidelines no longer. The Union Army of the Potomac had suffered two disastrous defeats at the hands of Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia at the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville and now Lee had set his eyes north. On June 4, 1863, just one day after Lee’s army began its trek toward Union territory, Drew was mustered into service with the 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry as the unit’s veterinary surgeon.[ii]

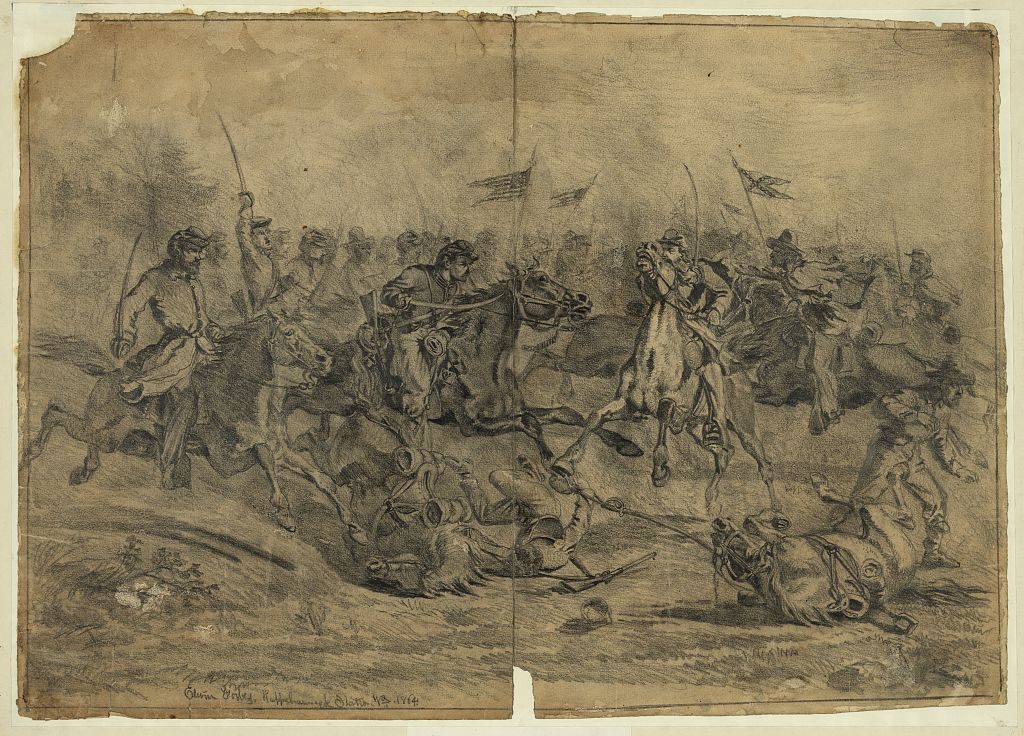

A mere five days after joining the 17th, Samuel Drew and the rest of his unit fought Confederate cavalry to a draw at the largest all-cavalry battle of the war at Brandy Station in Virginia on June 9. The fight brought with it a boost of morale and the important experience that came with.

Following a good performance at the Battle of Gettysburg less than a month later in July, 1863, the 17th Pennsylvania was called upon to scout Confederate lines south of the Rappahannock River. As the regiment made its way across the river at Sulphur Springs the wagon train that had accompanied the force was ordered back to Bealton Station, about ten miles north of their current position. In the chaos of the regiment moving forward and the wagon train retreating, Drew paused to assist a member of the train as he fixed up his wagon. Though kindness is a virtue, Drew’s sympathy put him in a bad position.

Attempting to catch up with the regiment, Drew had “gone about a mile when I saw three Cavalrymen a short distance ahead of me, dressed in our uniforms, (which is no uncommon thing.) When I came up to where I first saw them, they had turned off the road into some small pines, and did not see them, but I had gone only a few rods when I heard the tramp of horses behind me, coming at full speed. I turned in my saddle to see who it was, and I very well knew by catching a glimpse of a pistol in one of their hands, and a star on one of their hats.”[iii]

Believing in the capabilities of his horse to outrun his potential captors Drew muttered to himself, “Johnny Reb, you may catch me if you can,” and took off. Just as he had begun to elude the Confederates, he noticed two more men emerge on his right. “I was completely at their mercy, for I had no arms with me at the time.”[iv]

After capitulating, Drew’s thoughts went from trying to get away from the rebels to how these rebels might treat him as their prisoner. Going over this in his head while “wondering whether there was any humanity in my captors” Drew was then surprised to see another Union soldier wander his way to the group. The unfortunate Commissary Sergeant of the 17th had just stumbled into his own capture. While this was luckless for the poor sergeant, Drew saw in it a silver lining. “They brought him to where I was, for misery likes company, especially company that it has been in the habit of keeping, and I felt somewhat better by the appearance of an old familiar face.”

Less than a half hour later three more Union troops, this time from the 6th New York Cavalry, stumbled upon the fray and were also taken prisoner. Here began the long journey around the Virginia countryside. Starting in the vicinity of Culpepper Court House, the group made its way to Warrenton and then on to Salem where it stopped. At Salem the “captors then divided their spoils, as all they get in this way belongs to them…I had nothing left but what I stood in, not even a blanket to lay on. Some of my fellow prisoners had permission to keep one blanket.”

Deprived of just about everything, the next morning Drew and the other prisoners were then forced to march almost 20 miles to Rockford where the Confederate troops had planned on turning over the captives to infantry pickets. The would-be pickets had moved on, and it was the hope of the rebels that they would be found at Little Washington. This too was wishful thinking. A cold night followed by another fruitless march to Sperryville also produced no means of getting rid of the prisoners and finally the Confederates, who Drew later discovered were part of John S. Mosby’s command, continued the march to Madison Court House.

At Madison Court House it was now dark and almost three inches of snow had fallen during the afternoon. Mental and physical fatigue began to affect the men on both sides, but Drew felt a new spur of hope. While Mosby’s men negotiated with a local about housing the troops for the night Drew had taken notice of a large mountain behind the house that he believed would be a good place to find refuge.

“Overcome by fatigue, we sat down, as they supposed, but I did not…I made the bold attempt and reached the base of the mountain, and when half way up it they discovered I was missing. This was a trying moment for me; I could hear them coming and hunting around after me. I laid down amongst the leaves and covered myself over with them to conceal me. I lay in this uncomfortable position for two hours and could hear them talk very distinctly. I became very cold and stiff, and began thinking about getting back and making my escape.”

Creeping along the mountainside to find some semblance of a safe route to take, Drew found a main road which traced him back towards Sperryville. From here he found the Culpepper Pike and made his way towards the familiar town. About ten miles outside of Culpepper Drew ran into an African-American man who informed him that he was less than a mile from the Confederate pickets. He meandered aimlessly around the woods all day until he discovered the lights of Culpepper.

At first, this was a sight for sore eyes. Culpepper, however, was a place that had changed hands so many times over the length of the war that it was difficult to ascertain whether it was currently under Union or Confederate control. “To my joy I found it was occupied by our forces. It was 2 o’clock in the morning when I reached it, and learning that our Brigade was two miles beyond town, I concluded to remain until daybreak. Getting into a colored man’s shanty, I lay down on the floor, right glad to get a few hours refreshing sleep for my weary limbs.”

Samuel M. Drew’s brush with Confederate captivity did not dissuade him from continuing the fight. He was reunited with the 17th on Thursday afternoon. The whole ordeal had lasted only a few days but for this green soldier it was a story that he was glad to have lived to tell.

Drew was lucky to be able to rejoin the regiment and this was not lost on him or the men of his unit. “They were all somewhat surprised to see me,” he recalled of his triumphant return, “for they had already heard of my capture, and of course they thought I had taken rooms and lodging in Libby Prison, Richmond.”[v]

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

EJ Murphy is an educator and historian from Scranton, Pennsylvania. He teaches social studies at the Howard Gardner Multiple Intelligence Charter School and is a tour guide for the Waverly Community House’s Destination Freedom: Underground Railroad Walking Tour of Waverly. EJ has also written as a guest contributor to the Pennsylvania in the Civil War blog, is the co-host of the podcast Been Lit: The Hidden History of the Electric City, and has lectured about the Civil War era throughout Northeastern Pennsylvania.

Endnotes

[i] Wayne County Herald. November 21, 1889.

[ii] Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-65. Harrisburg, Pa: B. Singerly, State Printer. 1870.

[iii] Wayne County Herald. November 26, 1863.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.