Table of Contents

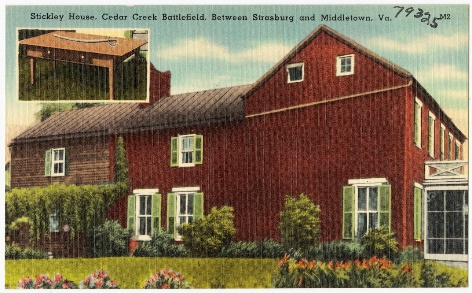

Tucked away behind a grove of trees just off Route 11 in northern Shenandoah County, Virginia is a brick farm house which sits on the banks of the small, babbling Cedar Creek. The quaint home has a few outbuildings scattered around it, adding to its peaceful surroundings. It is easy to forget that this property has a horrific and brutal past tied to the Civil War.

The farm and mill complex was built circa 1850 and belonged to the Stickley family. The Stickley’s were an average family in the Shenandoah Valley. Agriculture was the main occupation in the Valley, and wheat was king. The Stickley’s farm produced wheat as their main product, and their property along Cedar Creek allowed for an opportunity to build a mill to turn that wheat into flour.

Daniel Stickley ran the farm and mill complex with the help of his wife, children, and tenants that rented small houses and parcels of land from the family. Years later, a woman identified simply as “a girl from the Shenandoah Valley” but who was probably Mary Stickley, one of Daniel Stickley’s children, was interviewed about her life in the Shenandoah Valley. She mentioned that although her parents opposed slavery, “a family of slaves was willed to mother, and they came here to live.” It is not known if these slaves lived on the farm enslaved or as tenants.[1]

When the Civil War began, the Stickley family found themselves in the middle of the struggle. The Shenandoah Valley was important to both Union and Confederate forces during the war due to the vital supplies it produced for the Confederate Army, and its possible use as an invasion route into the North. The Valley Turnpike, the main highway through the Shenandoah Valley, cut through the Stickley’s property, and therefore the family witnessed many campaigns fought in the Valley during the war. A bridge spanning Cedar Creek on the Stickley property had been destroyed and rebuilt several times during the war to slow opposing armies, though this destruction was minor compared to other events. As Mary Stickley pointed out “we planted our garden every year, but we never knew who’d gather what we raised in it. The soldiers would take our onions and dig our sweet potatoes, and we couldn’t have apples or anything.”[2]

With the Stickley’s already struggling to survive in the midst of a warzone, life worsened in 1864. General Philip Sheridan took control of Union forces operating in the Shenandoah Valley in August 1864 and brought a significant threat to families in the Valley. Along with being tasked to destroy Confederate General Jubal Early’s Army of the Valley, Sheridan was ordered to lay waste to the Valley’s valuable resources. As Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah made one of their first moves against Early in August, they began that destruction, though minor compared to The Burning Campaign that was to come. The Stickley’s farm was directly in the path of this destruction. Mary Stickley recalled the event:

Shortly after dinner one day we looked out and saw that the flouring mill was on fire. It had stone walls, and the soldiers had piled up a lot of lightwood just inside of the door and started the fire in that wood. The wind was blowing, and the flames spread to the sawmill and to a small building that we used for [extra] work such as boiling apple-butter.[3]

Although officers ensured that no harm came to the family’s house, the damage to the farm and mill complex was devastating. In order to keep food on the family table Mrs. Stickley was forced to rely on nearby Union encampments to receive rations for her family.

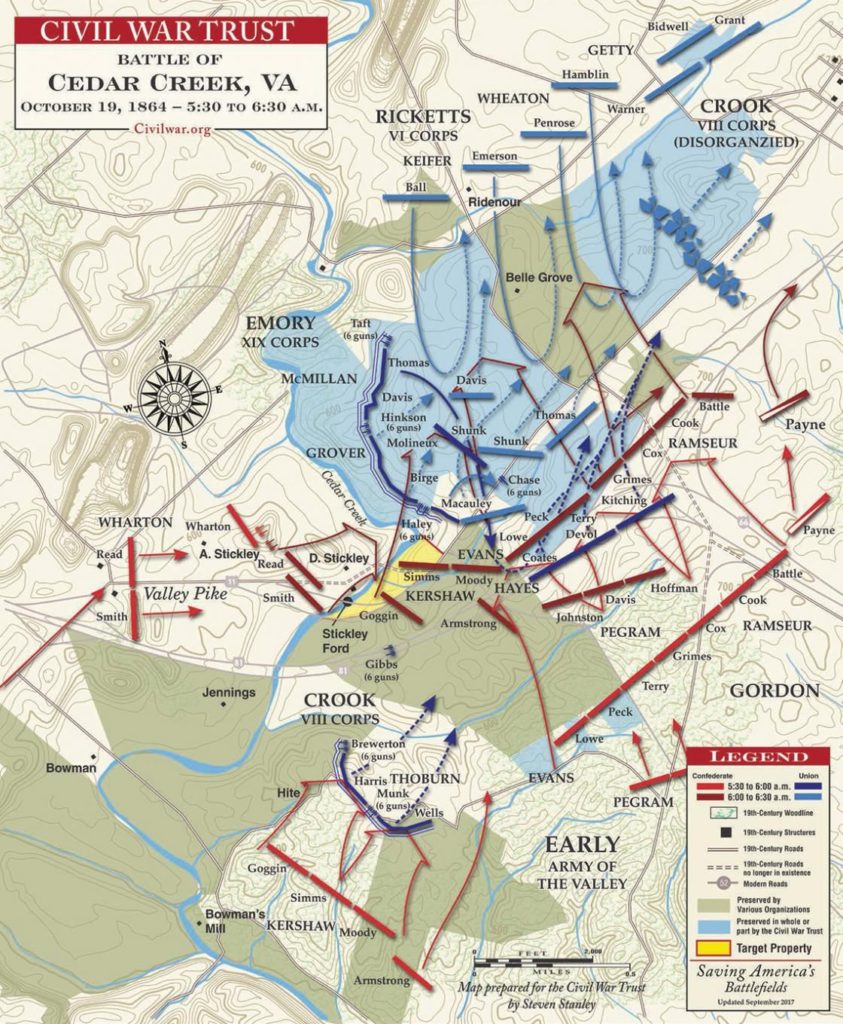

By October 1864 Sheridan’s bluecoats had defeated Jubal Early’s devastated army on several occasions in the Shenandoah Valley. Believing that Early’s forces were completely defeated, the Union Army once again encamped near the Stickley property with little belief that the Confederates might renew the contest.

On the morning of October 19, 1864, Confederate forces surprised and overwhelmed the sleeping Union Army. As the Battle of Cedar Creek commenced, Confederate surgeons began establishing field hospitals on opposite sides of the creek near the battlefield, making the Stickley property prime real estate for a hospital. Rev. J. William Jones described organizing a hospital site, likely at the Stickley property saying:

The surgeons, with due regard for the safety of the wounded, did not cross over the bridge, but established their hospitals on the western side. Very soon after a battle commences the wounded begin to come in – first those who can walk, holding a wounded hand or arm with the uninjured one, and then those more seriously wounded in ambulances.[4]

Soon after the battle began, wounded soldiers began pouring into the makeshift medical facility on the Stickley farm. The family’s table, which had been a gathering place to eat what meager food they had, was moved on to the porch of the house for use in surgical operations. A local boy went exploring on the battlefield after the Union Army had been forced from their camps. As he did, he came across the Stickley’s house and described the scene:

We went down toward the crick to where there was a big brick farmhouse that had been turned into a hospital. The wounded were inside the house and outside both. The front yard was full, and they lay there close together… On the back porch the surgeons were sawin’ off limbs… They had about a four-horse wagon load of limbs outside the porch in a heap just as you might pile up corn or manure.[5]

Upon seeing the terrible scene at the Stickley farm, the child began retrieving water for the wounded soldiers lying around the farm. As the battle continued, countless wounded men were brought to the farm house, “So many limb operations were carried out on one of the Stickley’s tables, ‘that the amputated arms and legs were piled higher than the table.’”[6]

As Confederate surgeons worked tirelessly at the Stickley’s house aiding the morning’s wounded, General Philip Sheridan completed his famous ride from Winchester to rally his shattered army. In the afternoon, reenergized Union soldiers launched a counterattack that turned a Confederate victory into a disastrous defeat. As retreating Confederate forces ran past the Stickley farm, Confederate surgeons quickly lit their medical wagons on fire, and fled the scene with the remnants of the Confederate Army. Mary Stickley recalled the burning wagons saying “the chemicals in them made a bright blaze.”[7] As Union surgeons arrived at the Stickley property, they continued the bloody work of their Confederate counterparts.

As the armies moved away from his property, Daniel Stickley was forced to clean the blood from his porch with a shovel, and many of the battle’s dead were buried on his property. After the war these bodies were reinterred elsewhere and a sense of normalcy slowly returned to the farmstead and family. Soon all that remained to remind the Stickley’s of the horrors they endured during the Battle of Cedar Creek was their bloodstained table.

Today that table can be seen at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. It represents how war can turn an intimate familial space into a horrific nightmare.

Learn more in this interview with James Horn, the post’s author

End Notes

[1] Lanier, Gabrielle M. “Draft Portion of Part IV, Historic Resource Study of Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park: The Daniel Stickley Farm and Mill Complex.” Historic Resource Study, James Madison University, 2009.

[2] Clifton Johnson, “Battleground Adventures: The Stories of Dwellers on the Scenes of Conflict in Some of the Most Notable Battles of the Civil War” (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, and Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1915), 383.

[3] Ibid, 387.

[4] J. William Jones, “Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume 16, The Battle of Cedar Creek,” Perseus Digital Library, December 27, 1888. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0273%3Achapter%3D1.50

[5] Johnson, “Battleground Adventures: The Stories of Dwellers on the Scenes of Conflict in Some of the Most Notable Battles of the Civil War,” 403-404.

[6] Theodore C. Mahr, “The Battle of Cedar Creek: Showdown in the Shenandoah, October 1-30. 1864” (Lynchburg, Virginia: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1992), 312-313.

[7] Johnson, “Battleground Adventures: The Stories of Dwellers on the Scenes of Conflict in Some of the Most Notable Battles of the Civil War,” 390.

About the Author

James Horn is a 2014 graduate of Shepherd University with a degree in Civil War History. He has worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park, and the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. In 2017 he published the book World War I and Jefferson County, West Virginia.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.