Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

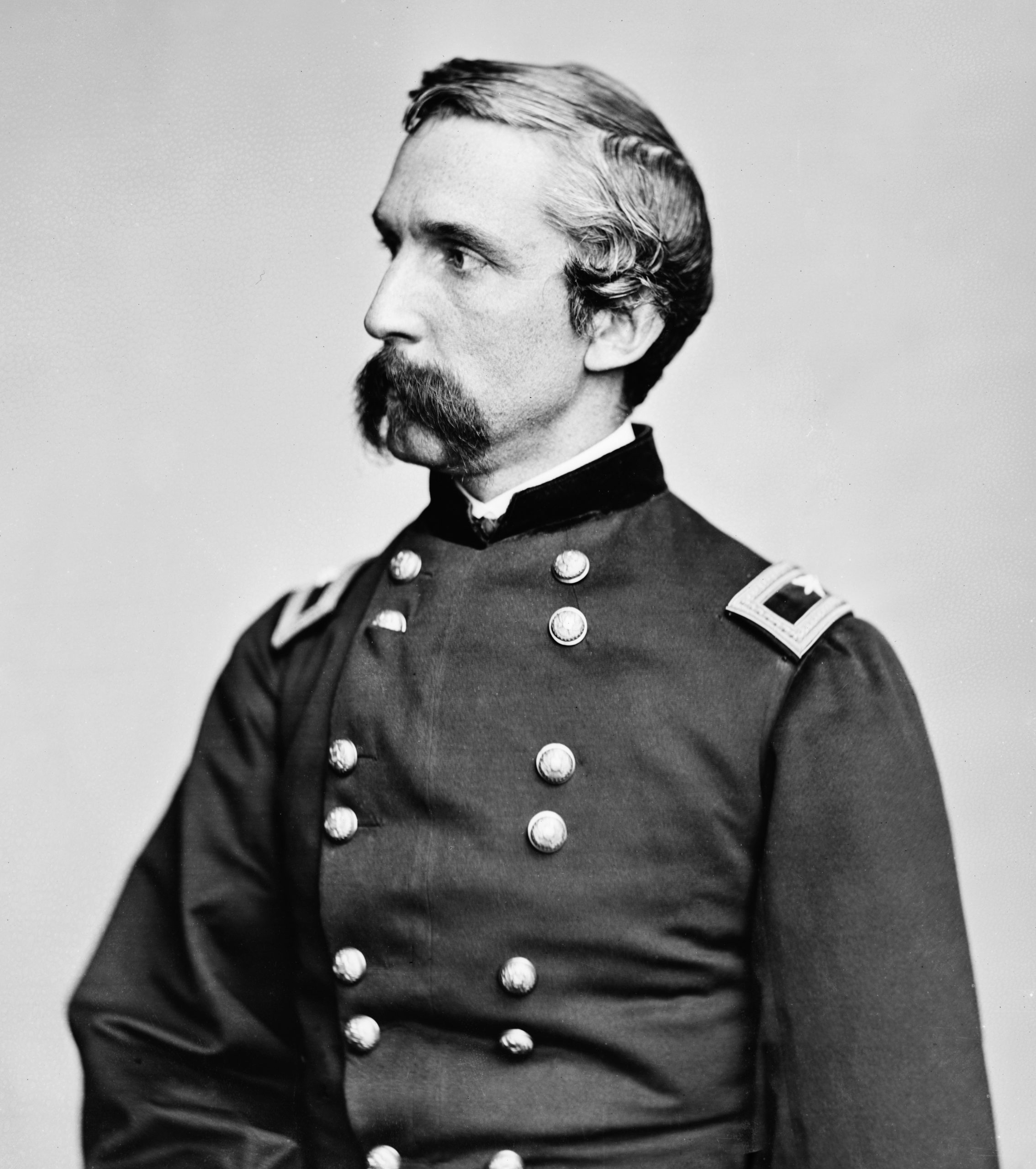

In a trembling hand, Brigadier General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain wrote the words he thought would be his last to his wife, Fanny, after midnight on June 19, 1864.

“My darling wife I am lying mortally wounded the doctors think, but my mind & heart are at peace Jesus Christ is my all-sufficient savior. I go to him. God bless & keep & comfort you, precious one, you have been a precious wife to me. To know & love you makes life & death beautiful.” [i]

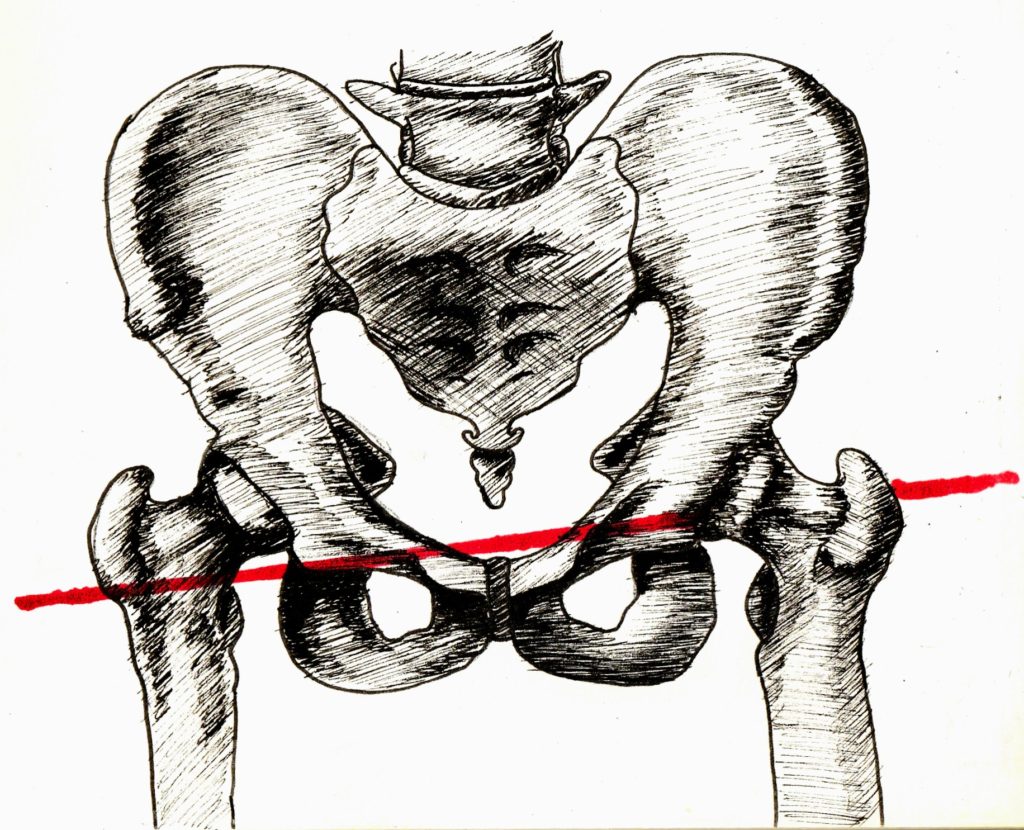

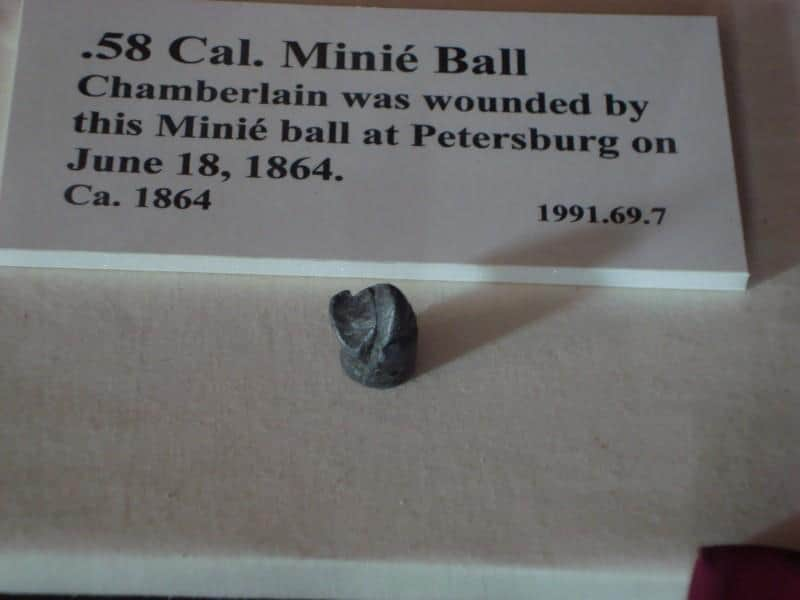

Earlier the previous day, while leading an attack on Confederate positions outside Petersburg, a rebel shot ricocheted off a rock and slammed into the general’s right hip as he led his men on foot. Upward and diagonal, the bullet shattered sections of his pelvis and ripped apart muscle, vessels, and passed through his bladder before coming to rest just below the skin on his left hip. Remarkably, he managed to stay on his feet with his saber jammed into the ground on one side and the brigade colors on the other until his men passed. There he fell, bleeding and certain of his approaching death.

He’d known it was coming, having said his farewells to a few men in camp the previous night.

“I had a strange feeling that evening, premonition of coming ill. I walked down through the ranks of my silent or sleeping men, drawing a blanket more closely over one … Having passed all through the deep spreading ranks, and went to my quarters and dropped into an unaccustomed mood. A shadow seemed to brood over me, dark wings folding as it were [or a pall] and wrapping me in their embrace. Something said; ‘You will not be here again. This is your last.’” [ii]

Stretcher bearers took Chamberlain to the brigade hospital three miles away, where surgeons attempted to extract the minié ball. While they pushed a ramrod through the hole in his body, his brother, Tom Chamberlain, searched field hospitals with Drs. Shaw (20th Maine) and Townsend (44th New York). Surgeons were certain Chamberlain would die, yet they labored through the night to reconnect vessels and urinary passages after removing the bullet. Sedated by morphine and chloroform, he nevertheless remained conscious, even instructing surgeons to carry on when they could no longer stomach the torture inflicted on him.[iii]

Exploratory field hospital surgery was far from the end of Chamberlain’s medical odyssey. Taken by the steamer Connecticut to the Naval Academy hospital in Annapolis, Maryland, he would go on to spend decades beating back death’s door.

Dr. Bernard Vanderkieft, head surgeon of Division I’s general hospital, took charge of Chamberlain’s case. It is not possible to know the exact damage, but modern urologists and orthopedists theorized the bullet tore through the bladder neck. He bled and leaked urine from the left hip, suggesting a bone fragment or other debris broke the skin as well. [iv] Dr. Vanderkeift’s main concerns were getting the bleeding under control and correcting the urine path despite not examining Chamberlain for at least two days after he was shot. Urosepsis set in almost immediately, causing severe chills, high fever, convulsions, delirium, nausea, and vomiting.

Despite a fatal prognosis, Dr. Vanderkieft decided giving Chamberlain a fighting chance meant an experimental procedure. He inserted an L-shaped catheter through Chamberlain’s urethra into his bladder in hopes of giving the rest of his pelvis a chance to heal.

Urethral catheters were first used 3,000 years ago in Rome, but they weren’t considered safe until thinner, flexible, sterilized materials were readily available in the 20th century. Benjamin Franklin was an early American to improve upon the catheter when his brother had to use one daily while battling kidney stones. He asked a silversmith to create a thinner, slightly more flexible version that didn’t do as much bodily damage. His design remained mostly unchanged through the Civil War, made from either silver or wood. Vulcanized rubber catheters were designed in the 1850s yet not often chosen over silver because they tended to disintegrate at body temperature and left behind debris. Patients frequently died of infections caused by the very catheters meant to save their lives.[v]

In Chamberlain’s case, Dr. Vanderkeift’s treatment plan often needed adjusting the longer he stubbornly refused to die. The surgeon reported to Dr. John H. Brinton that Chamberlain’s catheter had become encrusted after only five days. He knew the catheter needed frequent changing if Chamberlain required long-term use, yet the catheter was often left untouched for days.

Another infection set in, as did a fistula (a hole) at the base of his penis slightly anterior to the scrotum. The fistula most likely acquired during medical treatment caused more chronic problems for Chamberlain in the next fifty years than the actual minié ball hitting him on the battlefield. Orthopedic damage limited his ability to ride horses or walk long distances for years to come, while the fistula caused episodic infections, incontinence, loss of sexual function, and chronic pain.

Prolonged catheterization also caused scar tissue in the urethra that subsequent surgeries attempted to repair in 1865, 1866, and 1893. Growing scar tissue and damaged urinal passages meant Chamberlain evacuated his bladder from the fistula, not the urethra. In 1883, another surgery attempted to close the fistula by taking skin from the perineum to create a flap closure. Chamberlain’s surgeon was hopeful, and the procedure appeared to have worked for a few months until it opened again, making his chronic issues worse than ever. The combination of urethral scar tissue and the penoscrotal fistula probably caused an inability to ejaculate if achieving erection was even possible. Modern surgeons suggest post-traumatic stress would have limited his sexual function if the gunshot wound didn’t destroy it altogether since Chamberlain obtained leave for, among other things, neurasthenia (a historic term that suggests post-traumatic stress) in 1863.[vi]

Fifty years after being shot, in 1914, Chamberlain died of another urosepsis episode, making him one of the last Civil War veterans to die of complications from war wounds.

Today we take catheterization for granted as a common procedure. A person may enter the hospital for surgery or because they’ve got a urinary or kidney infection, and doctors insert flexible, thin, sterilized catheters. Patients experience relief once the tube is in place. If a secondary infection arises, simply feeding antibiotics into an IV will kill it. In Chamberlain’s day, there were no flexible plastics, no sturdy rubbers, and no antibiotics to fight off infections. Chamberlain managed to survive infection after infection as well as chronic pain, limited mobility, and mental anguish without the benefit of antibiotics or proper, accurate diagnoses.

We owe the safety and quick healing properties of modern catheters to the trial and error experimentation of Civil War surgeons like Dr. Bernard Vanderkeift. Soldiers like Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain endured unspeakable pain and sickness because, unfortunately, medical progress meant learning from materials, bacteria, and anatomy they didn’t understand. Since Chamberlain went through complications from prolonged catheterization, it helped surgeons understand how to change the way patients were treated. The collective of soldiers who were treated with catheters advanced that treatment by leaps and bounds in the Civil War, bringing us closer to the present day when people, like me, might have died from urinary and kidney infections without a catheter.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Jessica Jewett is an author and portrait artist living in Atlanta. She has been a lifelong student of the Civil War, specifically Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and medical topics, since her disability gives her a shared perspective with soldiers of the period. Both her books and art heavily focus on the war years as well.

Endnotes

[i] Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain to Fanny Adams Chamberlain. June 19, 1864. Special Collections Room, Hawthorne-Longellow Library, Bowdoin College, Brunswick, ME.

[ii] Smith, Diane Monroe. Chamberlain at Petersburg: The Charge at Fort Hell. (Thomas Publications, 2004), pp 3.

[iii] Harmon, William. McAllister, Charles K. “The Lion of the Union: The Pelvic Wound of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain.” The Journal of Urology. March 2000, pp 713-16.

[iv] Smith, Diane Monroe. Fanny & Joshua: The Enigmatic Lives of Frances Caroline Adams and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. (Thomas Publications, 1999), pp 155.

[v] A brief history of urinary catheters. (2019, April 15). Retrieved June 27, 2020, from https://www.urotoday.com/urinary-catheters-home/history-of-urinary-catheters.html

[vi] McAllister, C. K.: “Fire, Blood, and the Lion of the Union: Joshua Chamberlain’s Civil War Ailments.” The Pharos of Alpha Omega Alpha, 61: pp 40, 1998.