Table of Contents

Museum members are the reason we can bring you scholarship like this.

CONSIDER SUPPORTING THE MUSEUM TODAY

In the predawn darkness of May 3, 1863, Rice Bull, of the 123d New York, gripped his rifle-musket tightly as he anxiously lay in line of battle near the crossroads of Chancellorsville, Virginia. When the first rays of sun suddenly broke over the treetops behind him, Bull was warmed by the scene. “Never was there a more beautiful sunrise, not a cloud in the sky,” he remembered years later. “It seemed to me like sacrilege that such a sacred day should be used by men to kill and maim each other.”

By the end of the climactic fighting at the Battle of Chancellorsville that morning, Bull himself would be wounded and abandoned by the retreating Union army. He would spend the next week as a Confederate captive; the Union soldier’s harrowing ordeal, recounted in his post-war memoir, paints a vivid picture of the difficulties of caring for those left behind on a Civil War battlefield. For soldiers such as Bull, being wounded was only the beginning of their suffering.

Bull had been shot twice in the unrelenting Confederate assault that eventually broke the Union lines surrounding Chancellorsville on May 3. The first bullet entered his right cheek, glanced along the jaw bone, and exited his neck; the second punctured his left hip and ripped out through his back, leaving him a bloody mess. For the rest of that day and into the next, Bull and the other Union wounded around him simply lay where they had fallen amongst the detritus and carnage of the battlefield. “Most of [them] were quiet, saying little,” the New Yorker recalled. “All were weak and helpless from loss of blood, and seeming to have little interest in what was going on around them.”

The problem was the lack of available medical care. Bull claimed that no Federal surgeons had remained on that part of the field, and the Confederates likely had their hands full tending to their own men. John Larmon, a musician from Company I, did stay behind to care for the wounded. Although he had no knowledge of medicine, Larmon did his best to keep the men comfortable.

Throughout the afternoon of May 3, the musician tirelessly scrounged food from abandoned haversacks, spread blankets and ponchos over those that could not move themselves, and washed caked blood away from dirty wounds. Despite the courageous work of Larmon, however, Bull called the night of May 3-4 “sorrowful” because it was “the last night on earth for many who died for the lack of the care they needed.”

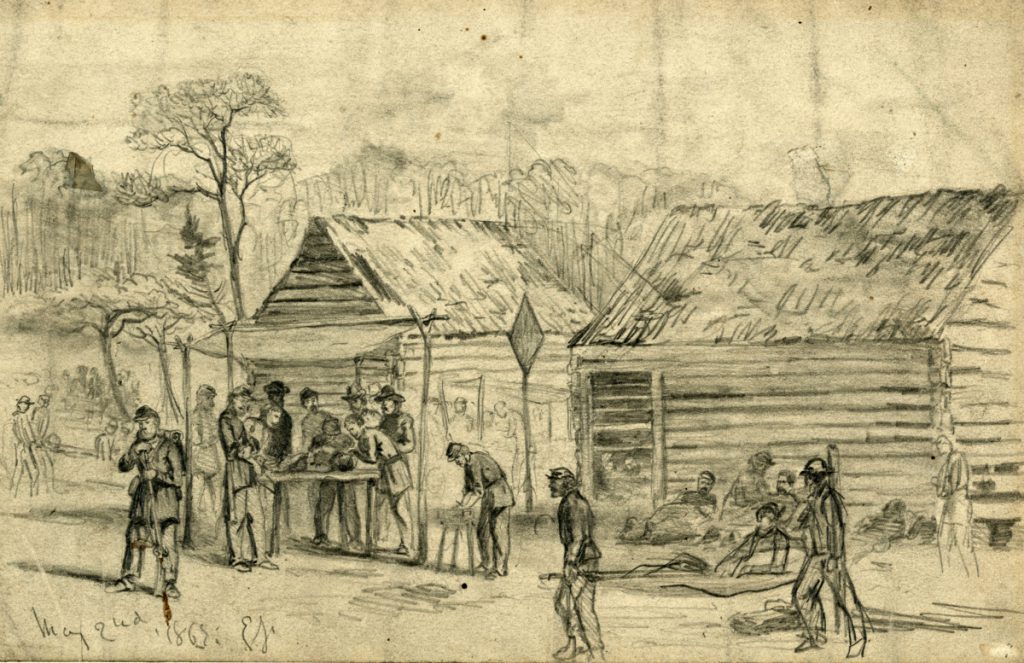

The following afternoon, a Confederate officer finally directed that all the surviving wounded be moved to a central location on a cleared elevation called Fairview, only several hundred yards from the Chancellorsville intersection.[1] There, a dilapidated log cabin, riddled by shot and shell from the previous day’s fighting, became the “center of [a] colony” of more than five hundred wounded men.

The musician Larmon, now assisted by Chaplain Thomas Ambrose of the 12th New Hampshire (whom Bull regarded as “one of the heroes of Chancellorsville”), continued to do all they could to make the wounded more comfortable. But without adequate medical care, many of the more severely wounded could not survive. Those that died were laid out, unburied, in the rear of an artillery lunette. An “awful odor” began to arise from the dead horses and men that lay around the makeshift hospital; “as time went on,” Bull remembered, “the stench became unbearable.”

Four Union surgeons finally arrived on the morning of May 5 under a flag of truce. They improvised an operating table using a large pantry door (taken from inside the log cabin) propped on two barrels, and began their grisly work in view of many of the other wounded. “As each amputation was completed the…man was carried to the old house and laid on the floor,” Bull wrote. “The arm or leg was thrown on the ground near the table, only a few feet from the wounded who were laying nearby.” Even the passage of fifty years had not softened this horrific scene for the New York soldier.

An intense thunderstorm erupted that afternoon. It ushered in a soaking, cold rain that fell for the next twenty-four hours. “The condition of most of the wounded was deplorable,” remembered Bull. Since most of the men did not have tents, they had to bear the full brunt of the storm and lay “sprawled in the mud and filth with nothing between them and the ground but their soaked woolen blankets.” Bull could distinctly remember their suffering, as they lay “half covered with the yellow mud and water.”

Even when the rain stopped on May 6, conditions did not improve. One man had been shot near the top of his head; his brain protruded from where the bullet entered his skull. This terrible wound caused him to act erratically. One night, in a fit of delirium, the soldier tore through the camp and trampled over three men lying on the floor of the cabin. His rampage tore open the sutures of their recently amputated legs, and the three soldiers bled to death before any surgeons arrived to help. “I could tell of incidents of this kind that occurred from day to day,” Bull wrote. “One reading about our camp might think I was exaggerating… [but there were] wounds of every conceivable kind, [and] the agony of mortally wounded men who lingered without aid until death came.”

Finally, on May 12, Bull and the other prisoners were informed that a Federal ambulance train was on its way to take them back across the Rappahannock River to Union lines. “When the news came, there was a faint cheer, for help was at hand,” wrote Bull. Those that survived the horrific nine days in captivity were placed into various Army hospitals. But for many, their terrible ordeal was not yet over.

“Not all of those who came back from our prison camp would see further service,” he remembered. “For some it was ended by their wounds, [while] others did not leave their hospital tent until they were carried away for burial.”

Rice Bull himself recovered from his wounds and returned to his regiment in the fall of 1863, which by that time had been transferred to Tennessee. Although his postwar memoir has been referenced by historians for many years, his horrific account of the wounded of Chancellorsville – no doubt similarly experienced by thousands of other soldiers throughout the war on both sides – is worth revisiting because it reminds us that the although the Civil War demonstrated improved evacuation of the wounded from battlefields, it was still not perfect. For many soldiers, the suffering did not end when the guns fell silent on the field.

Learn more in this interview with Nathan Marzoil, the post’s author:

Sources and Endnotes

[1] The Army of Northern Virginia also suffered grievous casualties during the battle – about 22 percent – so it’s likely they were occupied in caring for their own wounded. Bull did mention many Confederate soldiers helping Ambrose and Larmon provide basic care for the Union wounded, but there didn’t seem to be any trained doctors or surgeons. There was also a lack of medical supplies, shelter, and food.

K. Jack Bauer, Soldiering: The Civil War Diary of Rice C. Bull (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1977), 35-87. The original diary is the property of the Rensselaer County Historical Society, Troy, New York.

About the Author

Nathan Marzoli is a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C., where he specializes in unit history and leads staff rides to Civil War battlefields. He has a BA and MA in History from the University of New Hampshire. His publications include “‘Their Loss Was Necessarily Severe:’ The 12th New Hampshire at Chancellorsville,” and “‘We Are Seeing Something of Real War Now:’ The 3d, 4th, and 7th New Hampshire at Morris Island, July-September 1863” (winner of the 2017 Army Historical Foundation’s Distinguished Writing Award). He is currently working on a study of substitutes in the Union army.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.