Table of Contents

Museum members support scholarship like this.

On September 16, 1862, William Child, a young assistant surgeon in the 5th New Hampshire Infantry, sat down along the banks of Antietam Creek and pulled out a pen and paper. Child had been on the march through Maryland with the rest of the Army of the Potomac for nearly two weeks, and had crossed through the South Mountain battlefield the day before. It was Child’s first brush with the horrors of war. “Yesterday passed over a battlefield – how terrible – how awful,” he began to write to his wife, Carrie.[1]

At that moment, a Confederate battery on the other side of Antietam Creek opened fire, sending shells hurtling toward the Army of the Potomac. A terrified Child threw aside his letter and scrambled for cover. But as the shelling continued with no apparent threat to the 5th New Hampshire’s position, the young doctor picked up his pen again, writing – in a somewhat shakier hand – of the experience. “The sound of the guns and screeching of the shells make a devilish music such as I never heard before,” Child wrote. “This is the first battle you know.”[2]

Although it would not be William Child’s last experience with the brutality of war, the battle of Antietam and its aftermath proved an especially harsh trial for the young doctor. Child was detached from his regiment and remained at a field hospital near the battlefield for several months, so he was unable to escape the physical space of his baptism by fire. This exacerbated Child’s personal trauma, and his letters home, both to his wife and young children, document his struggle to process and make sense of the carnage.

William Child was born in the town of Bath, New Hampshire, on February 24, 1834. After graduating from Dartmouth Medical School in 1857, he returned home to open a medical practice in his hometown. He remained there until more than a year after the Civil War broke out. It was not until the summer of 1862, when President Lincoln placed a new call for 300,000 more volunteers, that Child decided to take advantage of the local and state bounties as New Hampshire worked to fulfill its quota. Child received his commission in the state capital of Concord on August 13, and was soon aboard a train and eventually bound for Newport News, Virginia. With him were a batch of new recruits, along with Colonel Edward Cross, the commander of the 5th New Hampshire who had been recuperating from wounds received in the spring campaign. Child joined the veteran regiment as their new assistant surgeon, just before they departed by ship for Aquia Creek, the Union landing and supply depot south of Washington. The regiment missed the fighting at Second Manassas at the end of August but did help to cover the retreat of the defeated Army of Virginia as they streamed back to the defenses of Washington. Only a few days later, Child and his regiment were on the march into Maryland with the rest of the Army of the Potomac as Maj. Gen. George McClellan tried to counter the Confederate invasion.[3]

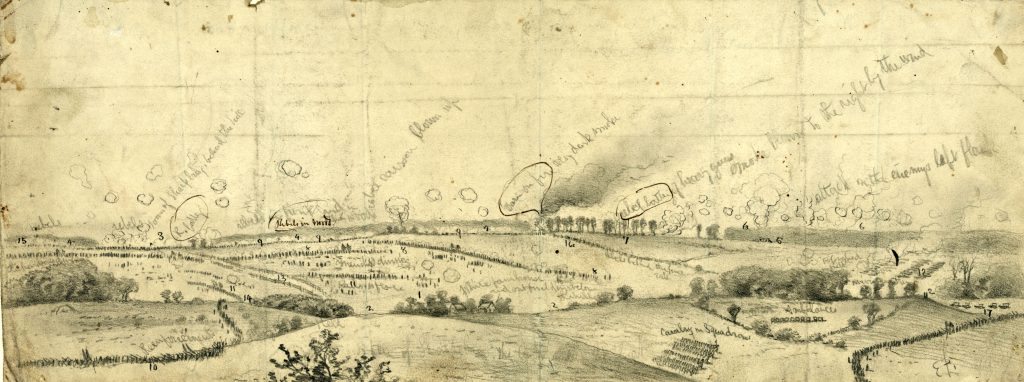

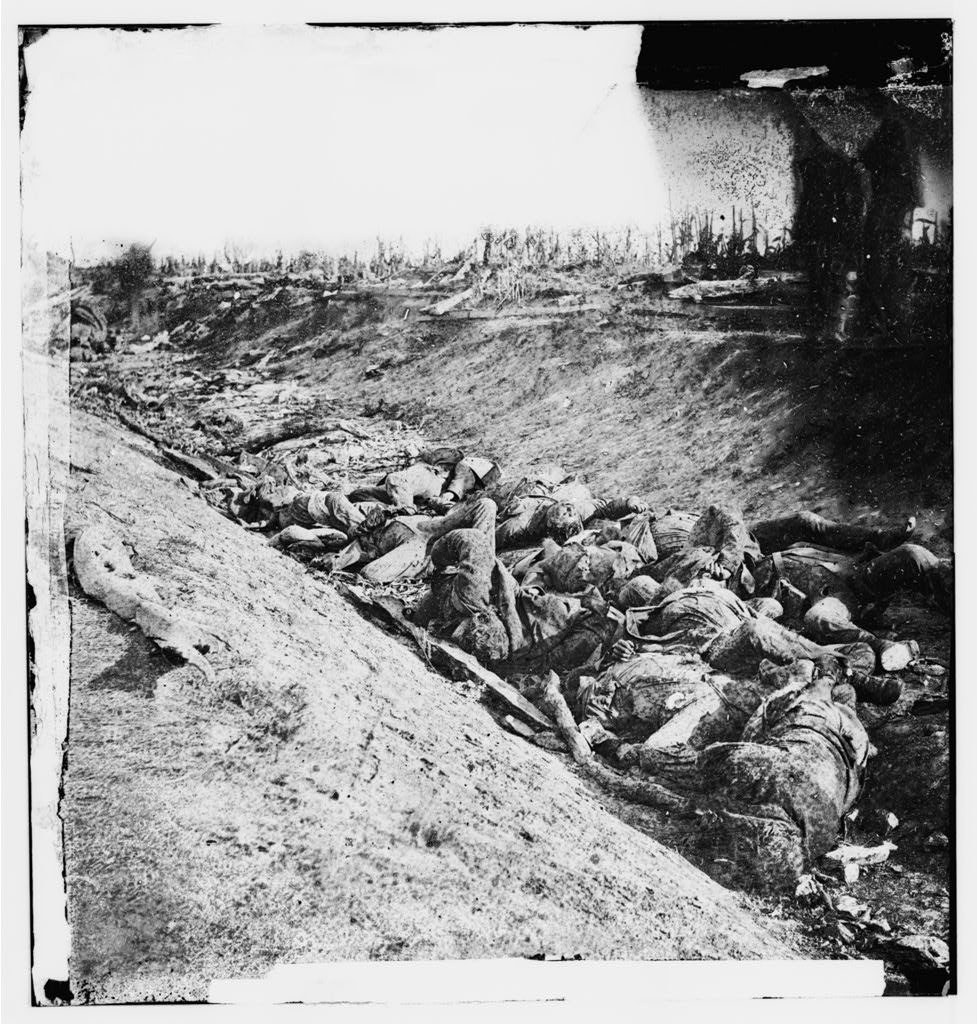

There was no major fighting for Child and his regiment on September 16, despite enduring the shelling that disrupted the young doctor’s letter writing. But on September 17, the 5th New Hampshire took part in a bloody assault against Confederates positioned in the Sunken Road at Antietam. As assistant surgeon, Child did not join the attack. But the carnage he witnessed in the coming days revealed to him the true horrors of war. In the days following the battle, Child worked himself into exhaustion, dressing wounds from sunrise until dark. The work convinced him that dying a quick death on the battlefield, no matter how violently, was a much better fate than that of the men who suffered for days and weeks afterwards. “The days after…are a thousand times worse than the day of the battle,” he wrote to Carrie five days after Antietam. “The dead appear sickening, but they suffer no pain. But the poor wounded mutilated soldiers that yet have life and sensation make a most horrid picture.” Child prayed that “God may stop such infernal work.”[4]

Because Child remained near the battlefield even as the rest of his regiment departed for the vicinity of Harpers Ferry on September 22, he found it difficult to escape the carnage. Death and destruction were everywhere; McClellan’s army sustained more than 12,000 casualties, with 3,000 Union soldiers falling in the fight for the Sunken Road alone (the 5th New Hampshire was relatively fortunate, with only eight men killed and 116 wounded). Wounded men filled nearly every barn and home around Sharpsburg, and the odor of decaying flesh lingered in the air. The physical devastation to the landscape – soldiers of both armies had picked apart the fields, fences, orchards, and barnyards of nearly every farm Child passed – was another constant reminder of the tragedy of war.[5]

In early October, Child was detailed as an assistant surgeon at a new hospital in the small village of Smoketown, just north of the battlefield. He optimistically looked forward to the posting where he would be able to gain good experience, telling Carrie that Smoketown was “a regularly organized army hospital such as I have not been in before.” But it was still incredibly hard work. Hundreds of patients filled the hospital, with “wounds in all parts you can think,” and Child spent most of his time dressing bullets wounds and stumps from amputated limbs. “The worst part,” he told Carrie, “is the bad smell” that came from the many gangrenous wounds.[6]

Dealing with human suffering, agony, and death on a daily basis began to wear on Child, and he struggled to reconcile what he saw with the supposed great Union victory at Antietam trumpeted by some of the northern press. “The masses rejoice,” Child told Carrie, “but if all could see the thousands of poor, suffering dieing [sic] men their rejoicing would turn to weeping.” He increasingly began to see the futility in war. “To see or feel that a power is in existence that can and will hurl masses of men against each other in deadly conflict – slaying each other by thousands – mangling and deforming their fellow men is almost impossible,” he wrote. “But it is so – and why we can not know.”[7]

Child ironically seems to have found it easier to explain his situation to his three-year-old son, Clinton. In one letter, Child wrote that he had seen “many sick folks” and that his work required him to sometimes “[make] much blood.” He also saw “much dead folk,” but assured Clinton that it always made him sick to see the deceased. “Out here men try to make other men ‘all dead’,” Child explained, but comforted him in writing that “they will not hurt papa.”[8]

One day, a local family with whom Child had boarded after the battle visited the hospital, bringing a basket of baked goods, butter, apples, and peach sauce as a gift for the surgeon. As the family, with their three young children, walked through the hospital ward with Child, a soldier who had lost his leg to amputation called one of the boys over to him. The soldier took the boy gently by the hand, and Child watched as tears began to stream down the soldier’s sunburned face. Despite not uttering a word, the interaction between this wounded man and young boy explained everything – and yet nothing – for William Child. He was reminded that “every soldier in this vast army, however humble, has an invisible but strong cord reaching away back to his loved ones at home.” Paraphrasing words he had heard somewhere long ago, Child summed up the scene to Carrie: “To the feeling man this war is truly a tragedy. But to the thinking man it must appear a madness.”[9]

Child finally departed the Smoketown Hospital and eventually rejoined the Army of the Potomac in Fredericksburg, Virginia just before dark on December 13, 1862. That day, the 5th New Hampshire suffered frightening casualties when they stormed the stone wall at the base of Marye’s Heights. Child had hoped to miss the fighting, but that night he found himself again hard at his ghastly work of treating wounded men. A few days later, he told Carrie that he had seen enough of war. “Some men might say that I was a coward to talk so,” he wrote, “but let them try it.” Child wished that “every person in Bath who has talked so savagely about this war could pass through one battle – see the suffering.” But his bloody work would continue. William Child was eventually promoted to full surgeon of the 5th New Hampshire and remained with the Army of the Potomac for most of the remainder of the war. In a final twist of fate, he was present at Ford’s Theater in Washington on the infamous night of April 14, 1865. “This night I have seen the murder of the President of the United States,” a shaken Child wrote to Carrie. “The wild scene…will never be forgotten by me. I shall remember the fiend like expression of the assassin’s face while I live.” William Child returned home to Bath in June 1865, his wartime service finally over.[10]

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Nathan A. Marzoli is a staff historian at the Air National Guard History Office, located on Joint Base Andrews. A U.S. Air Force veteran, he completed his bachelor’s degree in history and master’s degree in history and museum studies at the University of New Hampshire. Marzoli’s primary researching and writing interests focus on conscription in the Civil War North. He is the author of several articles, including “‘A Region Which Will at the Same Time Delight and Disgust You:’ Landscape Transformation and Changing Environmental Relationships in Civil War Washington, D.C.” (Civil War History); “‘We Are Seeing Something of Real War Now:’ The 3d, 4th and 7th New Hampshire on Morris Island, July–September 1863” (Winner of the 2017 Army Historical Foundation’s Distinguished Writing Award); “‘Their Loss Was Necessarily Severe:’ The 12th New Hampshire at Chancellorsville”; and “‘The Best Substitute:’ U.S. Army Low-Mountain Training in the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains, 1943–1944″ (Army History).

Endnotes

[1] Merrill C., Betty, and Timothy C. Sawyer, transcribers, Letters From a Civil War Surgeon: The Letters of Dr. William Child of the Fifth New Hampshire Volunteers (Solon, ME: Polar Bear & Company, 1995), 31.

[2] Sawyer, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 33.

[3] Sawyer, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 15; Mike Pride and Mark Travis, My Brave Boys: To War with Colonel Cross & the Fighting Fifth (Hanover, NH: University of New England Press, 2001), 114-121.

[4] Sawyer, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 33-34.

[5] Sawyer, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 37-45; Pride and Travis, My Brave Boys, 140.

[6] Sawyer, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 43-45.

[7] Sawyer, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 45-47.

[8] Sawyer, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 55-57.

[9] Sawyer, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 57. The saying Child was referencing in his letter was probably that attributed to 18th century British politician and writer Horace Walpole: “To the feeling man life is a tragedy, but to the thinking man it is a comedy.”

[10] Sawyer, Letters from a Civil War Surgeon, 69-73; 339-342; 366.