Table of Contents

The total casualty count of the American Civil War was approximately 1.6 million (Confederate and Union). The combined death toll of the Civil War eclipses the American totals of all other armed conflicts combined.[1] Even today, this number is still considered an estimate due to the loss of a large number of records as a result of the burning of Richmond, the Confederate capital, which consumed over 20 city blocks.[2] At the outbreak of war in 1861, both sides of the conflict were woefully unprepared for the realities of the situation and how many experienced doctors would be needed. Even today stories persist of injured left on the battlefield, excessive amputations being performed by inexperienced doctors, and casualties forced to “drag themselves to hospitals” where conditions were likely worse and disease rampant.[3] During the 1860’s, medical science was very much in its infancy. Unfortunately, the widespread acceptance of antisepsis in America didn’t come until after the Civil War and as such, medical historian Alfred Bollet cites one historical summary of the time as “the end of the Medical Middle Ages”.[4]

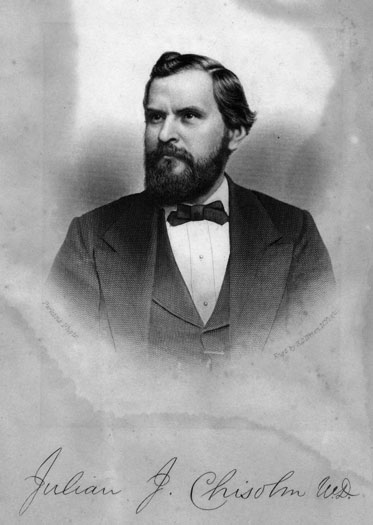

On the Confederate side, experienced and well-traveled doctors were quickly mobilized to spearhead the effort and provide as much information as possible to their medical communities. Dr. John J. Chisolm was one such practitioner who had the good fortune to witness care and treatment operations in multiple European conflicts and was able to provide that knowledge to doctors serving in the Civil War and beyond.

Owing to the need to build a medical corps from the ground-up, Dr. Chisolm contributed significantly to the war effort by working-at and mentoring others at the Confederate Capital of Richmond, Virginia. Additionally, Dr. Chisolm worked to counteract Union blockades by building medical laboratories. For example, he played a role in creating the research and drug plant in Columbia, South Carolina which opened during the Civil War. It was essential for the distribution of chloroform and ether both used as competing forms of nineteenth-century anesthesia.[7]

Despite these impressive accolades and contributions to Confederate Medicine, Dr. Chisolm’s perhaps most notable achievement was the invention of the Chisolm Inhaler. At the time, the most widely accepted method of the application of anesthesia was chloroform with a folded cloth.[8]

![Depiction of pre-Inhaler application of anesthesia[9]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/civil-war-amputation.jpg)

![Dr. Chisolm’s Inhaler[10]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Chisolm_ether_inhaler001.jpg)

After the war, Dr. Chisolm returned to medicine. He went back to school, returning to Europe to study Ophthalmology. In the late 1860’s, Dr. Chisolm relocated to Baltimore, Maryland where he took up the post of Chief of Eye and Ear Surgery at the University of Maryland.

Dr. Chisolm’s work in this field, included the opening of an eye and ear hospital nearby where his experiences/knowledge in anesthesia would benefit the field significantly. Dr. Chisolm’s notoriety in this area of medicine included a “crossing-of-paths” with Helen Keller. After an examination, Dr. Chisolm recommended a consultation with Alexander Graham Bell who connected Ms. Keller with Anne Sullivan.[13]

For his contributions to medicine, both during America’s greatest conflict to-date and during our country’s reconstruction, Dr. Chisolm truly was a pioneer of his time. Dr. Chisolm died in 1903 and is buried in Baltimore, Maryland.

Bibliography

Beller, Susan Provost. Medical Practices in the Civil War. Charlotte, VT., 1992.

Bollet M.D., Alfred Jay. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson: Galen Press, 2002.

Chisolm M.D., J. Julian. A Manual of Military Surgery For The User Of Surgeons In The Confederate States Army; With Explanatory Plates of all Useful Operations. Columbia: Evans and Cogswell, 1864.

Hambrecht, F. T., M. Rhode, A. Hawk. “Dr. Chisolm’s Inhaler: A Rare Confederate Medical Invention.” Journal of the South Carolina Medical Association 87, 5 (1991). 277-280.

Lankford, Nelson. Richmond Burning: The Lady Days of the Confederate Capital. England: Viking Penguin, 2002.

Medical College of the State of South Carolina. “Julian John Chisolm: Class of 1850.” http://waring.library.musc.edu/exhibits/civilwar/Chisolm.php

Medical College of the State of South Carolina. “Union Blockade.” http://waring.library.musc.edu/exhibits/civilwar/Blockade.php

Reilly, Robert F. “Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861-1865.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4790547.

Endnotes

[1] Robert F. Reilly. “Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861-1865.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4790547.

[2] Nelson Lankford. Richmond Burning: The Lady Days of the Confederate Capital. England: Viking Penguin, 2002, 216 pictures.

[3] Alfred Jay Bollet, M.D. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson: Galen Press, 2002, 7.

[4] Bollet, 37.

[5] Medical College of the State of South Carolina. “Julian John Chisolm: Class of 1850.” http://waring.library.musc.edu/exhibits/civilwar/Chisolm.php

[6] Bollet, 59

[7] Medical College of the State of South Carolina. “Union Blockade.” http://waring.library.musc.edu/exhibits/civilwar/Blockade.php

[8] F. T. Hambrecht, M. Rhode, A. Hawk. “Dr. Chisolm’s Inhaler: A Rare Confederate Medical Invention.” Journal of the South Carolina Medical Association 87, 5 (1991), 278; J. Julian Chisolm, M.D. A Manual of Military Surgery For The User Of Surgeons In The Confederate States Army; With Explanatory Plates of all Useful Operations. Columbia: Evans and Cogswell, 1864, 428.

[9] Susan Provost Beller. Medical Practices in the Civil War. Charlotte, VT., 1992, 73.

[10] Beller, 74

[11] Bollet, 80; Hambrecht, 277

[12] Hambrecht, 279

[13] Bollet, 59

About the Author

Rob Seliga lives a quiet (read: hectic) life in Mount Airy with his wife and two boys while balancing a career in IT and the prospect of being a born-again historian. Lately, he can be found attending classes at Hood while chasing that elusive Masters Degree, but in his spare time enjoys spending time with his family, reading, and the occasional video game.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.