Table of Contents

This is the second in a series of posts about Clara Jones, a Civil War Nurse.

As the school year drew to a close in the summer of 1862 in Philadelphia Clara Jones, a grammar school teacher, had settled into a comfortable routine. “I go visit at the hospitals and then run errands and come home…I wish I could take up my abode permanently in one of those institutions I think I would be quite contented”[1] Soon she would make her wish a reality.

School closed on July 9, 1862 and by August, Jones had started full-time hospital work…aboard a boat. The State of Maine was one of many of Northern vessels equipped to treat and transport wounded soldiers from the front to more permanent hospitals.[2] Over the month of August, the State of Maine transported more than 3,000 sick soldiers and exchanged prisoners of war between the Virginia Peninsula near Fort Monroe and Point Lookout, Maryland.

Though preferring to care for Union soldiers, Jones’ first trip aboard the ship carried about 1,000 Confederate prisoners from Fort Monroe to near Richmond. There they would be exchanged for 1,200 Union soldiers from the infamous Libby Prison in the Confederate Capital. As Clara remembered, each of the Union soldiers “had some words of gratitude — ‘Thank you madam’ ‘God Bless you Miss’…O! that I were able to remain among the suffering always. I have shed more tears since they came aboard and yet felt happier than I’ve been in months.”[3]

Her relief efforts on the ship typically involved offering the soldiers comforting food and drink. “The supply of wine and jelly contributed by my dear girls was found very acceptable as were the pickles which I, myself, distributed among them…I saw men sit down and cry like children to find themselves once more under the protection of our flag, and receiving the comfort that they had so longed for”[4]

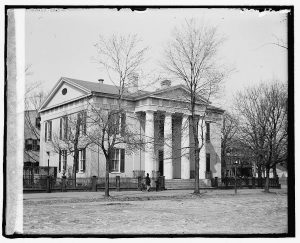

By early September, the State of Maine was commandeered by the United States Quartermaster Department and went out of service as a hospital ship. With school out of session until the first of October, Jones vowed to remain active for the whole month. She visited Dorothea Dix, the Superintendent of Nurses, in Washington to request an assignment. Dix told Jones that there was no use for her due to Jones’ limited availability. Not one to take no for an answer, Jones met with another contact she had at the Surgeon General’s office. There she had more luck. Jones was stationed at the Lyceum building, a large public lecture hall converted into a hospital, in Alexandria, Virginia.[5]

While at the Lyceum, Jones encountered her most challenging work as a nurse to date. She recorded in her diary that she “found 60 badly wounded men without a nurse, without comforts of any kind…The smell arising from the undressed wounds was perfectly dreadful. I have been hard at work making beds and washing faces ever since my arrival this evening and I think the men will rest more comfortably.” Within a day, Jones observed that her presence and care made the men “more cheerful than last night.”[6]

Jones was hardly volunteering for the glamour or notoriety. Her room at the Lyceum was tiny. She recorded that she could touch two opposite walls at once from her bed. She did have offers from several local residents to stay in their homes, but Jones “declined their kind offers because [she] wished to be near the patients and because [she was] independent.”[7]

She oversaw 11 attendants, six white and five black. Jones was critical of the black attendants, “they are never here – they seem to disappear just when they are needed and they are more trouble than all the sick.” While her attitudes were ahead of her time regarding female equality, the same cannot be said for racial equality. This goes to show the complexity inherent in historical actors. They can be laudable in many ways and frustrating in others.[8]

Beyond changing dressings and attending to the cleanliness of the hospital, Jones wrote letters “daily for the men, particularly for those who [she knew were] in a critical condition.”[9] Death became a common feature of life for her while working at the Lyceum. Jones reported seeing between one and three soldiers’ funerals per day.[10]

As Jones was making preparations to leave Alexandria in early October (having obtained an extra month’s leave from school), she came down with typhoid fever. “The doctor…assured me that I could not possibly escape having one of 3 diseases—Typhoid, Jaundice or Boils.”[11] An epidemic of typhoid fever had broken out among the patients at the Lyceum about two weeks earlier. After a week of bedrest in her small room, Jones felt well enough to travel home to Philadelphia by October 19. By November 1st she had largely recovered and resumed teaching again at Rittenhouse Grammar School.

Her time among the wounded in Virginia would not be her last time comforting the wounded. In the summer of 1863, the Civil War came to her home state and Clara Jones would have a major role to play.

Learn more on this subject with John Lustrea, the post’s author

This is the second in a series of four posts on Clara Jones, a Civil War Nurse. Click below to be directed to the others.

Endnotes

[1] Clara Jones to Lane Schofield, July 17, 1862.

[2] Leading up to the summer of 1862 Jones was trying to plan a summer trip where she could volunteer at a hospital outside of Philadelphia, closer to where the armies resided. In a letter written to Schofield on July 7, 1862 she claimed she was “making every exertion to obtain passage on one of the boats engaged in carrying the sick and wounded.” She did end up on the State of Maine, but we do not know exactly how she ended up there or why such a prospect was so appealing to her.

[3] Clara Jones to Mr. Hollingsworth, August 3, 1862.

[4] Jones to Harriet, August 19, 1862.

[5] Jones to Mr. Hollingsworth, Sept 5, 1862.

[6] Clara Jones Diary, September 6-7, 1862.

[7] Jones to Unknown, September 12, 1862.

[8] Jones to Unknown, September 12, 1862.

[9] Jones to Unknown, September 12, 1862.

[10] Jones to Unknown, September 16, 1862.

[11] Jones to Mr. Hollingsworth, October 9, 1862.

About the Author

John Lustrea is a member of the Education Department at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He earned his Master’s degree in Public History from the University of South Carolina. Lustrea has previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park the past four summers.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.