Table of Contents

This is the third in a series of posts about Clara Jones, a Civil War Nurse.

Volunteering in a Civil War hospital was a risky venture as Clara Jones found out in the summer of 1862. Having caught typhoid fever, she spent several months recovering – complaining often of the prescribed doses of quinine. The trying experience would not stop Jones from feeling eager for school to be out of session so she could be free of her teaching duties and resume her nursing efforts. In fact she was so determined to return to the front that she proclaimed she would do so “even if the plague threatened.”[1]

One of her former patients “wrote me such a kind letter that…I want to go and improve upon what I have done.”[2] It did not take long for that to happen. A month and a half after leaving, Jones made a joyous return to the Lyceum in Alexandria to cook a Thanksgiving meal for 60-100 men.

Over the winter recess from school, Jones brought more food and medical supplies to convalescents in Alexandria and the Army of the Potomac where it camped at Belle Plain near Falmouth, Virginia.

When winter break ended, Jones went back to the daily routine of teaching and occasionally volunteering at hospitals in Philadelphia when she had time. The end of school in the summer of 1863 coincided with the battle of Gettysburg, the largest of the Civil War and the closest calamity yet to Clara Jones.

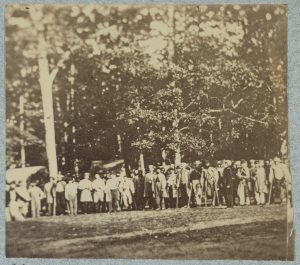

She arrived in Gettysburg by train from Baltimore on July 19 and reported to the Second Corps field hospital. They had about 500 patients, 100 of whom were Confederate soldiers.[3]

“I left [a dying rebel soldier] very sorrowfully, far from home and friends, with no prospect of sending a message to a heart-broken wife or mother their most bitter enemy would not refuse the tear of pity.” As it turns out, several did refuse the wounded and dying Confederate soldiers tears of pity.[4]

After being seen by a surgeon, the Confederate soldiers did not receive attention from most of the field hospital’s volunteer nursing staff, who were not required to treat all patients equally, so Jones offered to tend to the Confederate wounded. It was all Jones could do sometimes just to get a pillow for them to rest their heads on since some hospital aids occasionally refused outright to give any comfort to Confederate soldiers. Institutionalized International Humanitarian Law which introduced strict provisions to treat all wounded noncombatants regardless of their allegiance had not yet been established, although unspoken rules existed to care for the wounded of both sides.

Jones wrote, “We lose 12 men a night, the Dr. says we shall lose half of them in 2 weeks. There is scarcely a tent that has not a dying man. I am busy in the evenings writing for them. The suffering among them is beyond description. Some are wounded in such a manner as to make amputation impossible and the poor fellows die without help. Our men seem to stand it better than the Rebels. I see a great deal of both, perhaps I pay more attention to the latter than any other lady in the camp because I see them neglected by the rest.”[5]

As bad as conditions seemed, Jones was quick to credit the doctors for their good work, refuting the modern stigma that Civil War medicine did little good. She reported that, “I give all our Surgeons credit for much care…although the mortality was great, it would have been far greater had they been less attentive.”[6]

When Jones needed a break, she would occasionally explore the surrounding area that had been the battlefield. “The atmosphere in the neighborhood of the Cemetery and indeed for miles around was most offensive,” Jones wrote. “The fields were dotted with the half-consumed carcasses of horses and the roadside was strewn with them half decayed which our men had not yet had the time to burn.”[7]

An aspect of Jones’ service often remarked upon by her patients at Gettysburg was her singing voice. She sang both individually with soldiers and in the hospital-wide prayer meetings. When she saw some of her former charges at another hospital the first thing they said to her was that “‘No one sings for us here!’”[8]

“I have felt a strange happiness in performing my duties here,” Jones concluded about her service in Gettysburg. “Every exertion I have made for the comfort of the poor men has brought its own reward, and I have been repaid a hundred fold, for what little discomfort I have suffered.”[9]

By August 6, two and a half weeks after Jones arrived, the last patient had been removed from the Second Corps field hospital near Gettysburg to more permanent general hospitals in larger cities. Since school was still out, Jones and two of her friends went back to Baltimore to resupply and set off for Rappahannock Station where the Army of the Potomac was located to distribute food and more medical supplies.

Getting permission to join the army proved to be more challenging than anticipated. As Jones remembered, “It took three determined women nearly nine hours, petitioning, requesting, insisting as the case required, till the pass to the Army located at Rappahannock was gained. It was nearly night when the victory was won.”[10]

Their arrival at Rappahannock Station made them the only women to visit the army during its post-Gettysburg campaign. This prompted a remark from the commanding General George Meade that “‘Ladies! If you’ve got here you’ll get anywhere.’”[11]

Learn more on this subject in this video with John Lustrea, the post’s author

This is the third in a series of four posts on Clara Jones, a Civil War Nurse. Click below to be directed to the others.

Endnotes

[1] Jones to Schofield, October 21, 1862.

[2] Clara Jones to Lane Schofield, October 19, 1862.

[3] Clara Jones Diary, July 20, 1863.

[4] Clara Jones Diary, July 20, 1863.

[5] Clara Jones Diary, July 20, 1863.

[6] Clara Jones Dirary, August 5, 1863.

[7] Clara Jones Diary, July 20, 1863.

[8] Clara Jones Diary, August 9, 1863.

[9] Clara Jones Diary, August 5, 1863.

[10] Clara Jones, “To Rappahannock 1863.”

[11] Clara Jones, “To Rappahannock 1863.”

About the Author

John Lustrea is a member of the Education Department at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He earned his Master’s degree in Public History from the University of South Carolina. Lustrea has previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park the past four summers.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.