Table of Contents

More than just a warm drink, coffee became a ritual that Civil War soldiers looked forward to – a small luxury that provided some semblance of normalcy and comfort and a reminder of home amidst the chaos of war. For Confederate soldiers who faced severe ration shortages due to Union blockades, coffee and its substitutions became symbols of both scarcity, solidarity, and resistance, uniting them in their shared deprivation.

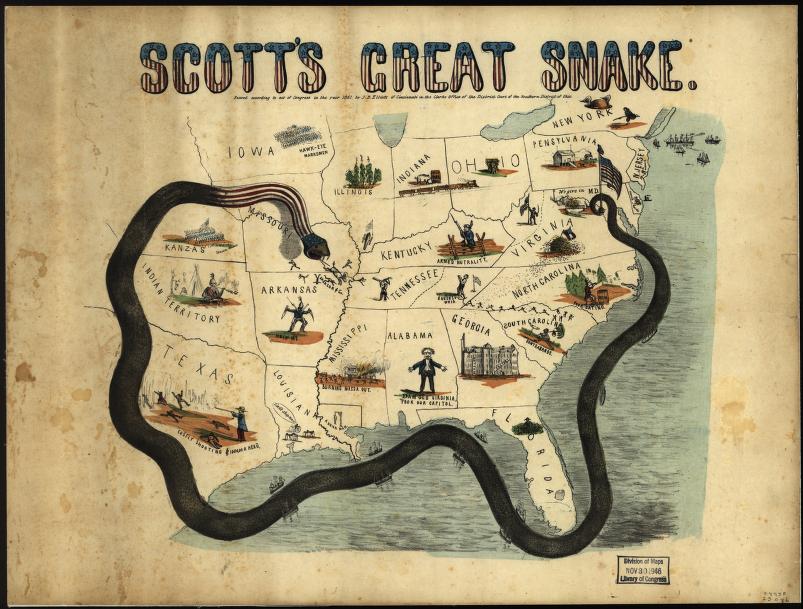

The relationship between the Confederate Army and coffee was vastly different than that of the Union. The Southern bombardment of Fort Sumter, South Carolina in early April 1861 led the United States into the Civil War and quickly became the impetus for Northern retaliation. On April 19th, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln penned a proclamation that called for the creation of a federal blockade for the all the ports located in the states of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Less than ten days later, Lincoln further added Virginia and North Carolina to the list.[1] General Winfield Scott pressed Lincoln to expand the blockade and proposed the Anaconda Plan which would prevent trade from occurring along the Mississippi River in collaboration with the blockades of the Southern coastline. Sensory historian Mark Smith argues that Lincoln’s cabinet knew that the creation of an “artificial famine… would wear down the resistance and end in abject, humiliating, gut-gnawing surrender and was designed to achieve that end.”[2] The blockades implemented during the Civil War were designed to constrain the South and quell the growing rebellion. These blockades not only limited the South’s access to crucial supplies and food imports like coffee but also reshaped the personal experiences of Southern soldiers and greatly influenced their memories of coffee.

By January 1862, coffee was one of the first staples that was officially eliminated from the rations of the Confederate soldiers as the shipments of the beverage from South America were no longer arriving in ports.[3] While Union soldiers came to depend on coffee as a daily routine, Southern soldiers displayed resistance to Lincoln’s blockade with remarkably resourceful methods for creating pseudo-coffee. By hand-crafting their own versions of the beverage using unexpected ingredients and forging new routines that mimicked that of the Union troops, Southern soldiers demonstrated how coffee was still vital to the morale of the Confederates even if they no longer had access to it. Going forward from 1862, Confederate soldiers either had to capture coffee rations from Union soldiers, be gifted coffee from civilians, illegally trade across picket lines while risking capture or death or utilize culinary creativity to brew a hot beverage akin to that of the roasted bean.[4]

To achieve the brewing of a cup of “coffee” sans coffee beans, the enlisted Confederate soldiers took to attempting to use any object or item that could potentially achieve that particular flavor. Historian John Fisher explains that some of the most common substitutes for this would be “acorns, sweet potatoes, okra seeds, persimmon seeds, barley, rye, wheat, corn meal, field peas, cotton seeds, chicory, garden peas, and beets.”[5] Additionally, Civil War historian William Davis explains that to achieve that specific flavor, these found ingredients would need to be first boiled, dried, and roasted or charred over an open flame.[6] Here is where the camaraderie of coffee and that of the Confederate soldiers can be best observed. The communal gathering of items to be used required multiple hands in foraging. When it was time to begin, the group would need to start a fire to boil water and cook the ingredients to alter the flavor, such as the acorns which are particularly bitter, and others would be responsible for ensuring that the roasted ingredients did not acquire too dark of a char. When the ingredients and methods of preparation were complete, the men could sit around and enjoy the fruits of their labor together and still have access to the same conversation and feel of community that the soldiers in the Union Army had.

James Fremantle, a British officer who had spent time behind Confederate lines, most notably at the battle of Gettysburg in 1863, noted in his diary that “the loss of coffee afflicts the Confederates even more than the loss of spirits; and they exercise their ingenuity in devising substitutes, which are not generally successful.”[7] Fremantle’s observation highlights the cultural and emotional importance of coffee during the Civil War encapsulating coffee’s importance not just as a beverage but as a cultural artifact, but by revealing the deep personal and societal connections to everyday comforts amidst the disruptions of war.

Albert Goodloe, an infantryman in the 35th Alabama, recalled that when his regiment was in a sugar producing region, they greatly utilized this ingredient in their attempts to make coffee. Goodloe wrote that after having made “so-called coffee out of one thing and another for a long time, we finally made coffee out of sugar… this was the best of all substitutes that I had ever seen; the color and odor and flavor resembling coffee in a surprising manner.”[8] His reminisces of wartime shortage also mention the use of various substitutions that were used in coffee preparation such as toasted parched wheat and rye, and that generally roasted and dried sweet potato would be the best option on a regular basis. Sam Watkins, an infantryman in the 1st Tennessee, had been assigned to official foraging detail which led him far from the war-ravaged countryside. Here, a civilian invited Watkins in for a hot meal and noted in his reminisces that what he found on the table for dinner was an incredible sight. Watkins joyfully wrote “did my eyes deceive me? Well, there was sugar and coffee – genuine Rio – none of your rye or potato coffee… I dive in, I go in a little too heavy, I dive in heavier.”[9]

These Confederate narratives greatly indicate the ongoing want and appreciation of coffee for the soldiers in the South, and the lengths they went to achieve its creation. While the camaraderie and teamwork required to brew this beverage was drastically different from that of the Union soldiers, the value and appreciation for the beverage remained the same. The Confederates’ profound sense of loss over coffee compared to spirits suggests that coffee was not merely a commodity but a deeply ingrained part of their daily lives and morale. The attempts to create substitutions not only reveal the ingenuity of the Confederate soldier, but also their adaptability in replicating the unique cultural and psychological role coffee played. This reinforces how coffee, as a staple of 19th-century life, had become an irreplaceable part of both Northern and Southern identities.

Sources

[1] “The Blockade of Confederate Ports, 1861–1865.” U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, history.state.gov/milestones/1861-1865/blockade. Accessed 27 Nov. 2024.

[2] Mark Smith. “The Hollowing of Vicksburg.” The Smell of Battle, The Taste of Siege (Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2015), 92–93.

[3]Bell Irvin Wiley. The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (Louisianna State University Press 2008), 102-103.

[4] John C. Fisher, and Carol Fisher. Food in the American Military: A History (McFarland & Co, 2011), 74-75.

[5] Fisher, Food in the American Military, 74.

[6] Davis, A Taste for War, 43.

[7] James Fremantle. The Fremantle Diary: A Journal of the Confederacy (Burford Books, 2001), 73.

[8] Albert Goodloe. Confederate Echoes: A Voice from the South in the Days of the Secession and of the Southern Confederacy (Big Byte Books, 2024),123-124.

[9]Samuel R. Watkins. “Co. Aytch” (Chattanooga, Tenn., Times printing company, 1900), 83-84.

About the Author

Katie Migneault is both a professional chef and a culinary historian finishing her MA in History at University of Massachusetts-Boston. She works as the Retail Manager at the Museum and keeps a jar of hand-made salt pork on her desk.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.