Table of Contents

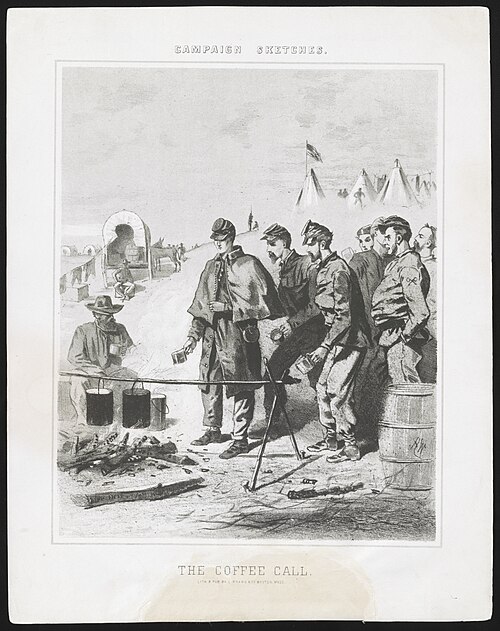

During the Civil War, coffee served not only as a physical stimulant, helping soldiers endure fatigue and the monotony of military life, but also as a powerful social catalyst. Gathered around campfires, soldiers brewed and shared coffee, transforming this simple act into a shared experience that fostered a sense of brotherhood and mutual support. As veteran John Billings, of the 10th Massachusetts Light Artillery, noted in his memoir Hardtack and Coffee, these moments created “friendly intercourse” among soldiers, lifting their morale and allowing them to escape, if only for a few minutes, the grim reality of war.[1]

In Part II of this series on coffee in the Civil War, we look at the Union Army.

For Union soldiers, coffee was a reliable and generously supplied ration, symbolizing the logistical strength of their army and offering a consistent source of comfort and social bonding in camp. Through coffee, soldiers not only sustained their bodies but also nurtured their spirits, reminding us of the enduring power of simple comforts in building community under the harshest of conditions. The Union government’s prioritization of coffee in the soldiers rations also heavily contributed to a fondness for the beverage.

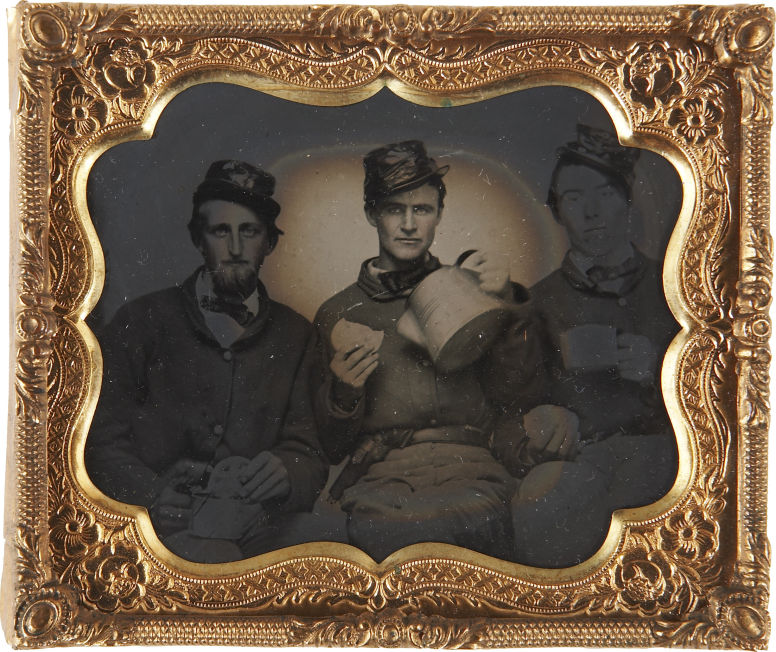

For the soldiers in the Union, more often than not, the coffee beans were issued unroasted and arrived in camp in its natural green state. The soldiers themselves were not issued coffee mills, so it became the responsibility of those who wanted a cup of coffee to first acquire their rations and then roast them for consumption. Billings noted in his accounts that at the time of issuing, a large blanket would be opened, and small piles of coffee would be set out for each man. Billings explained that “… the care taken to make the piles of the same size to the eye to keep the men from growling would remind one of a country physician making his powders, taking a little from one pile and adding to another.”[2] Similarly, Wilbur Hinman, of the 65th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, remembered “that when they were apportioned to each man… the grains were scrupulously counted off so that he might receive his full share.”[3] Both of these recollections underscore the interplay of coffee and togetherness within the Union Army by emphasizing the communal practices surrounding the issuance of coffee rations. The issuing of green, unroasted beans required individual soldiers to take on the labor of roasting and preparing their coffee, creating a sense of self-reliance, personal agency, and competence. At the same time, the shared experience of coffee rationing cultivated a daily routine for the men to partake in. The meticulous division of coffee, as recounted by both Billings and Hinman, reflects a collective concern for fairness that bolstered group cohesion. Billings’ analogy to a country physician balancing his powders highlights both the precision and the care involved in this process, while Hinman’s emphasis on counting grains illustrates the importance of equity in maintaining harmony among soldiers. Together, these accounts suggest that coffee was more than a beverage; it was a ritual that blended individual effort with shared experience, reinforcing bonds among men in the hardships of war.

Soldiers prepared and drank coffee at regular intervals, making it the beverage of choice for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and everywhere in between. On long marches, brief periods of rest allowed them to quickly savor a warm cup of coffee. Many would pre-prepare the grounds before setting out so that, when the time came, only boiling water was needed. Billings recalled how soldiers on the march fell into a routine each evening to make their coffee and wrote, “as soon as the fact was known… that the army was on the point of bivouacking… little campfires increasing to hundreds in number would shoot up and soon be surrounded by soldiers who made it almost an invariable rule to cook their coffee first.”[4] Hinman recalled that “every other man squatted on the ground or knelt beside a log and with the butt of his bayonet and pounded the grains…one superintended the coffee by roasting the grains in a tin cup or can, and another watched the water coming to a boil.[5]

The mentions of coffee in personal documents and letters home highlight its role as a topic of great importance that bridged the gap between the battlefield and civilian life and also connected soldiers to both their immediate environments and to the loved ones they were writing to. Lewis Bissell, an artilleryman from the 2nd Connecticut, wrote in a letter to his wife “coffee could not be dispensed with – I don’t know how I could get along without it on a long march.”[6] Hinman recalled post-war, “it was an elixir to the weary body and drooping spirit after a fatiguing march; it warmed the soldier into new life when soaked by drenching rains or chilled by winter’s cold.”[7] In writing home about coffee, the emotional weight and importance of the beverage’s importance is underscored – it became not just a drink but an emotional anchor, revitalizing both the body and spirit amidst adversity. In camp, it allowed soldiers to bond, exchange stories, and momentarily step away from the relentless pressures of combat, reinforcing the social ties critical for their collective resilience.

Sources

[1] John Davis Billings. Hardtack and Coffee, or, The Unwritten Story of Army Life (University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 108.

[2]Billings, Hardtack and Coffee, 128.

[3]Wilbur F. Hinman, et al. Corporal Si Klegg and His “Pard” (University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 459.

[4] Billings, Hardtack and Coffee, 29.

[5] Hinman, Si Klegg and His “Pard”, 76.

[6] 1996. Soldier Life. Alexandria, Va. (Time-Life Books), 80.

[7] Hinman, Si Klegg and His “Pard”, 207.

About the Author

Katie Migneault is both a professional chef and a culinary historian finishing her MA in History at University of Massachusetts-Boston. She works as the Retail Manager at the Museum and keeps a jar of hand-made salt pork on her desk.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.