Table of Contents

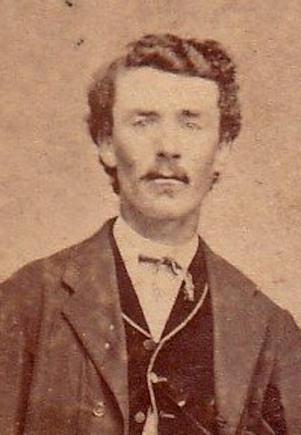

Joining the Washington Mounted Rifles in May 1861, Thomas Wallace Colley – from Abingdon, Virginia – had no idea of what the future held. Like most young men, North and South, Colley had a burning desire to join the fray before the one great battle all believed would end the war. Soon, folks across the land realized the conflict would prove long and bloody. Tom Colley realized his share of the fighting and incurred three wounds while riding with the 1st Virginia Cavalry.

Maneuvering his command into position before the Second Battle of Manassas, Major General Jeb Stuart’s cavalry engaged in a skirmish at Waterloo Bridge on August 22, 1862. Colley later recalled: “…another ball came spurting through the leaves and struck me on the instep of my right foot and made a slight but painful wound. I crouched down and grunted awhile and examined my foot and saw it was not serious. I soon found that I could not let my foot hang down in the stirrup, so I fixed a cushion out of my blankets in front and carried my foot upon the horse withers.” This first wound, while slight, marked the first of three Colley received during the war. The second wound nearly took his life.

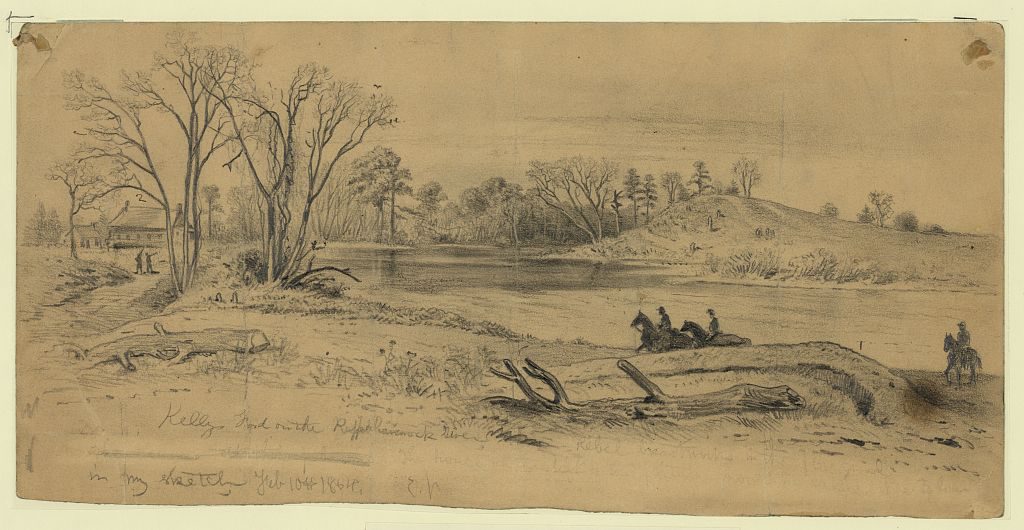

While riding toward Kelly’s Ford on March 17, 1863, the Federal horsemen of Brigadier General William Woods Averell’s command encountered Confederate resistance, as, in increasing numbers, they crossed the ford and approached dismounted Southern sharpshooters. Confederate Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee then charged with his cavalry, Colley among them. The intensity of the action grew, and Colley, still mounted, approached a stone wall and began firing toward the Bluecoats with his carbine. Suddenly, things went wrong! Colley’s horse nervously halted, “…when all of a sudden some 15 or 20 shots came from a clump of pines at an old fence row some 80 yards away from where we stood.” Colley’s comrades began to fall back. Tom had dismounted to remove a heavy coat, when “…a bullet came under my horse’s neck and struck me some 2 ½ inches on my left side, from the pit of my stomach, and passed through my body coming out some 2 inches lower down near the small of my back, slightly injuring the spinal column.” Falling to the ground, Colley, barely conscious, heard his comrades avow, “Tom is killed.”

Falling back to a position in the rear, his comrades left Tom on the field to die. Thankfully, a trooper of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry found Colley, gave him water, and summoned a Federal surgeon to inspect the wounded foe. Upon examining the wound, the surgeon declared “…it was impossible for me to live but a short time and desired to know if I had any words to loved ones.” Colley requested they transport him to the nearby Wheatley farmhouse, where he could live out his last moments inside a comfortable home instead of breathing his last while lying in the mud. Once inside the home, Tom listened “…to my ‘Life’s Blood’ fast trickling away.”

Meanwhile, on the battlefield, the Confederates rallied and drove Averell’s men from the field. Once the gray-clad troopers discovered Tom continued to cling to life, they summoned a Confederate surgeon to report to the Wheatly home quickly. Much as the Federal physician had told Colley, the Confederate surgeon “…examined my wound, pronounced it fatal; as there were no bones broken he could do nothing.” Tom’s father, learned of his son’s dire-condition and traveled to care for him, although he expected to find him dead based on the reports he had received. However, Tom lived! His father “…stayed with me until I was able to start home – twenty-five days after I was wounded. I gradually improved and done quite well until my appetite came to me and I began to crave solid food. The doctor and I had it hot and heavy for several days before he would agree for me to have bread and milk.”

Convalescing until late May of 1864, with a period of service at a horse depot in Gordonsville sprinkled in, Tom rejoined the 1st Virginia Cavalry a few days after Jeb Stuart died of his mortal wound at Yellow Tavern. Joining his comrades again made Tom incredibly happy.

Federal Major General Philip Sheridan sent Brigadier General David Gregg’s Division to Haw’s Shop in Hanover County, Virginia, just north of Richmond, to hold the critical position where five roads converged. Major General Wade Hampton had overall command of the Confederate forces on the field, and Brigadier General Williams C. Wickham led the brigade with Colley and the balance of the 1st Virginia Cavalry.

At some point during the seven hours of fighting at Haw’s Shop on May 28, 1864, Colley and five other members of the 1st Virginia advanced to a fence line amid the dense undergrowth on the field. Fighting dismounted, Colley recalled a “…ball struck me ½ inch in front of my boot heel and passed through the sole and up to the ankle bone on the outside and ran around the joint lodging against the ankle bone on the inside, completely shattering the joint. As the shock deadened my limb I did not feel any immediate pain.” Later, he “…began to feel a stinging sensation on my ankle bone and the blood was running up my boot leg. When I rose and attempted to put my weight on it, the bones crushed and I would have fallen to the ground had not two of my companions…ran to me and caught me.” Next thing Colley knew, “Our Chaplain was giving me some whiskey in a glass tumbler. I was put in an ambulance and hurried off to Atlee Station, and some 40 of us, all wounded, were packed in a ‘horse car’ and sent down to Richmond that night.”

Surviving a painful ambulance ride, Colley occupied a bed in the Old Jackson Hospital. His spirits darkened, and he “…was quite low for some three weeks. I do not know anything that went on around me. I had a violent fever. I was insensible to pain; attributed my condition to the deadly effects of the Chloroform.” Writing to his brother, Colley shared the ordeal of amputation. “I thought I would have it [left foot] amputated before I would risk suffering what I am. I am doing quite well. My physician says he never saw a wound doing better in all his experience.” Colley continued to recover from the amputation, and writing to his brother again, expressed a special request. “I wish you to ask Doctor Owens to give me a piece of sponge. There is so much Erysipelas and Gangrene here that I would like to have a piece [sponge] of my own.”

Tom survived the war, later enrolled in a business college in Baltimore, and married in 1872. He and his wife eventually had 12 children, and Tom struggled to support a growing family. Holding several jobs, including deputy-sheriff of Washington County, presented the veteran with many challenges. Yet, he persevered.

Read more about this trooper’s fascinating wartime exploits, and his postwar struggles with what we now call PTSD, in this writer’s newest book from the University of Tennessee Press, In Memory of Self and Comrades: Thomas Wallace Colley’s Recollections of Civil War Service in the 1st Virginia Cavalry. Readers can learn more at www.civilwarhistorian.net.

About the Author

Michael K. Shaffer is a Civil War historian, instructor, lecturer, newspaper columnist, and author. Shaffer is a member of the Society of Civil War Historians, Historians of the Civil War Western Theater, Georgia Association of Historians, and Georgia Writers Association. He also teaches Civil War Courses at Kennesaw State University’s College of Continuing and Professional Education and frequently lectures to various groups across the country.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.