Table of Contents

A Neglected Epidemic during the Civil War

Season Two of Mercy Street is the first episodic or cinematic depiction of a smallpox epidemic, which left dead over 60,000 newly freed slaves during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Traditional stories about emancipation portray enslaved people hearing the news of the Emancipation Proclamation and praising Lincoln and even God for freedom. Other representations highlight how the war brought an end to slavery or how freedpeople escaped from bondage. None of these illustrations reveal how enslaved people survived the following day.

Where did they find shelter, food, or fresh water? Since the war was the largest biological crisis of the nineteenth-century, with disease causing more death than battle, how did enslaved people survive living in the South where infectious disease took the lives of so many Union and Confederate troops?

Mercy Street powerfully depicts the utterly harsh, impoverished conditions that formerly enslaved people confronted once they were liberated. Set in Alexandria, Virginia, which is a stone’s throw from Washington, DC, the show tells the story of how a Southern hotel was converted into a hospital for Union troops. But the show also takes the viewer outside the hospital, where the military created a makeshift camp for enslaved people who freed themselves from slavery, and were heading to the North to enjoy their freedom. The series’ representation of former slaves as refugees in a camp is a shocking and important reminder about the actual conditions that followed in the immediate aftermath of slavery. These camps were overcrowded and unsanitary, and the freedpeople in them lacked the basic necessities to survive, making them increasingly susceptible to a smallpox outbreak that began in Washington, DC, and slowly crept into Alexandria.

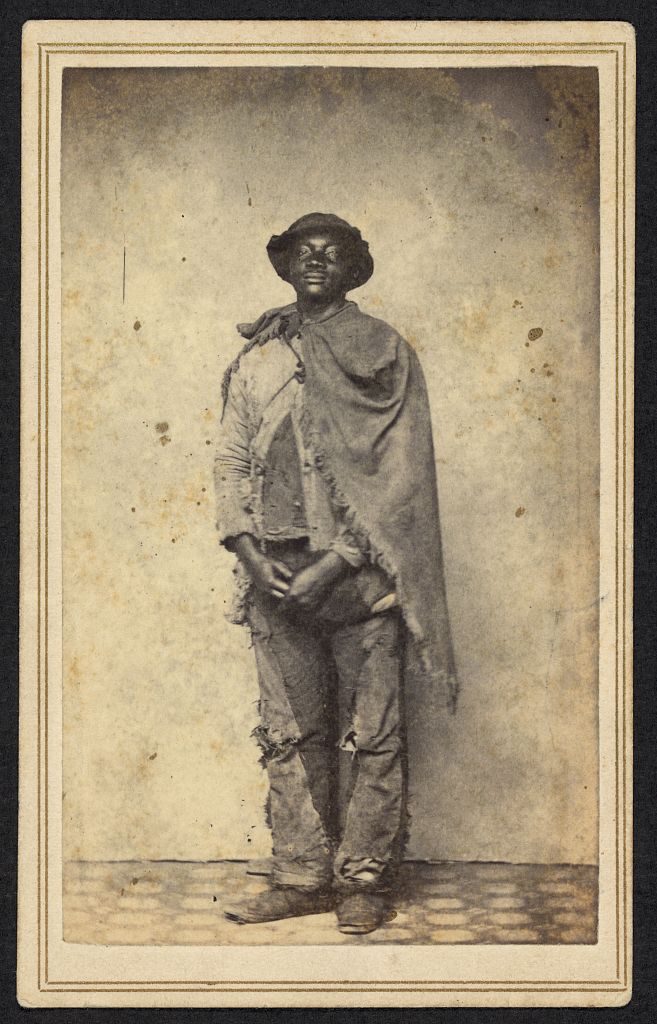

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In the show, Charlotte Jenkins, an African-American Northern reformer, who arrives in Alexandria from the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society, first discovers signs of an epidemic. She sees a young black mother laying on the ground with her child. Smallpox had begun to erupt on the women’s face. This is a powerful scene because it vividly shows what emancipation was for so many former slaves, particularly for women and their children. While the military recruited men to work as laborers in the army and enlisted others as soldiers, freedwomen were left with little if any opportunity to earn an income in order to survive. More freedwomen and children succumbed to the epidemic than men. In fact, throughout the research for my book, Sick from Freedom, I found countless references to freedwomen dying on the side of a road, in abandoned barns, or on a deserted battlefield. There was even more reports written by Union military officials describing the “destitute” and sickly condition of freedwomen, who arrived at their camps, begging for support.

The image of the freedwoman in Mercy Street infected with smallpox sharply challenges the popular narrative of freedom as a simple triumphant story. Seeing this woman, who later dies from the infection, reveals the unintended consequences of emancipation. When President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, he did it as a military strategy to outmaneuver the Confederacy. While it proved effective, there was no policy in place in order to address the day-to-day realities of emancipation. As Mercy Street shows, mothers died in freedom, leaving their daughters alone in a town that portended freedom but did not offer this young character a bed to even sleep in that night.

Charlotte Jenkins’ character was inspired by real-life reformer Harriet Jacobs. Jacobs escaped from slavery in North Carolina and traveled to New York. During the Civil War, Jacobs traveled back to the South in order to help formerly enslaved people. She had gone to Alexandria to establish a school, but like Charlotte Jenkins, Jacobs discovers the epidemic and redirects her efforts to trying to stop the virus from spreading.

At the time of the Civil War, physicians knew how to prevent smallpox. Beginning in the late-18th century many doctors led by Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia, developed citywide protocols that mandated vaccination and inoculation to stop the spread of the virus. By the time of the Civil War, this legislation remained hotly contested, but doctors were aware of a protocol to follow to prevent further infection. While the unexpected outbreak of smallpox in the Civil War South drew heavily on medical staff’s already limited resources, doctors knew how to circumvent even that challenge. They could fallback on quarantine measures: isolating infected patients in tents, rooms, or hospitals.

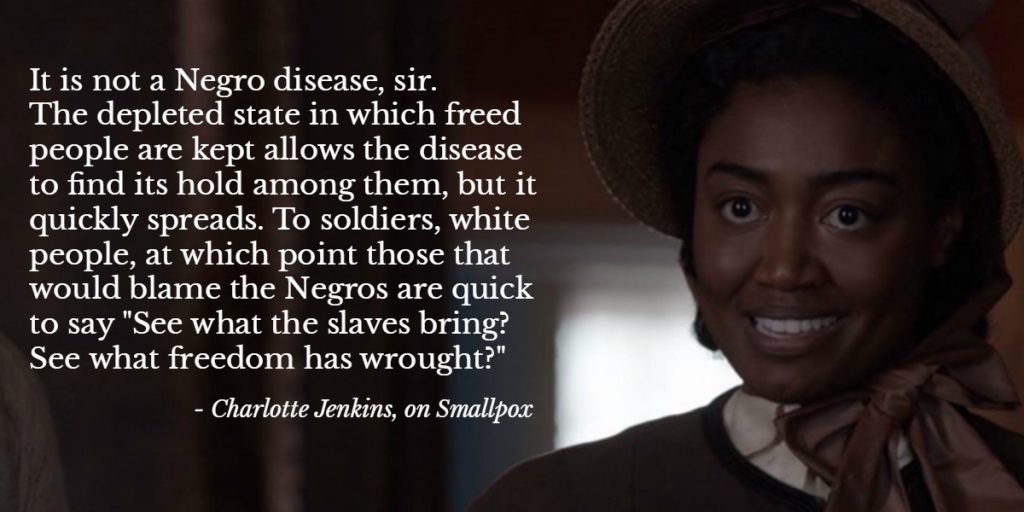

When Charlotte Jenkins discovers smallpox on the freedwoman in Mercy Street, she pleads with the physician at the Union hospital for the resources to establish a quarantine tent. While the physician initially denies her request, she reminds him that the epidemic does not respect the color line and that soon the white residents in Alexandria could be infected. Dr. Foster eventually acquiesces, especially since the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society will be primarily funding the project—not the Union Army.

In Mercy Street, the director reflects real life structural differences in the treatment of white soldiers, and the newly-freed African Americans. While white characters are sheltered in the hospital, the black characters are left outside. In real life, the difference in levels of care between white soldiers and freedpeople were even more stark.

The Mercy Street tent is much more sophisticated than what many enslaved people would have placed in during the war. Within the Mercy Street tent, there are beds and white blankets and lanterns and a wooden medicine cabinet; there are plenty of dishes, bowls, and even a nurse distributing food. The actual quarantine tents during the war were made of used, ripped and worn army tarps; the blankets would have been infested with lice and fleas. There were no beds or wooden cabinets. Sick freedpeople would have been lucky to even secure a space within the military camp to pitch a quarantine tent, let alone one that had a hanging lantern. These structural differences led the epidemic to skyrocket among the black population. In turn, the rapid rate of infection fueled racist thinking that the outbreak resulted from black inferiority.

Mercy Street has accomplished something quite remarkable. They have insisted on portraying the chilling, unexpected effects of emancipation. They have told a story about an epidemic that has often been ignored in popular and cinematic accounts the war. They have highlighted Harriet Jacobs, an American hero and they have included the anonymous women and children, who like their flesh and blood counterparts in history, died without us knowing their name or even hearing a sentence about how they planned to celebrate their freedom.

Learn more in this interview with Jim Downs, the post’s author

Additional Resources

- Jim Down’s Book: Sick From Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Harriet Jacobs’ Autobiography

About the Author

Jim Downs is the author of Sick From Freedom: African American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction and is an associate professor of history at Connecticut College.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.