Table of Contents

In the week before the bloodiest day in American history at Antietam, the Defenses of Washington teemed with soldiers. As many as 70,000 men crowded the camps and garrisons, most from the Army of the Potomac, on the march or encamped awaiting orders, or in the forts surrounding the capital, and others on special duty or part of provisional units.

But among this mass not all served with their commands. These included convalescents from the hospitals, no longer requiring treatment but also neither discharged nor well enough to rejoin their units. There were also men on leave, authorized or not, those attempting to return from leave, and those who’d simply dodged or deserted from their regiments.

One such regiment, supposed to be in the field with the Twelfth Corps, had so worn itself out in the previous summer’s campaign that their nominal division commander would report after Antietam that “The First District of Columbia Volunteers had, with the exception of the colonel and adjutant, entirely disappeared from the command by sickness and desertion.”[i]

On September 10, exactly a week before the great battle, stragglers (perhaps some from the regiment mentioned) looted the commissary storeroom in Alexandria and the next day General Heintzelman, newly in command of the Defenses of Washington, received the following instructions:

Some arrangement must be made to collect all the stragglers and convalescents who are now wandering about Alexandria and Washington, unable to rejoin their regiments, and keep them together until an opportunity offers to send them back. General Banks [thinks] it would be best to establish a general camp in some central position on the Virginia side, and to order the military governors of Alexandria and the District of Columbia to pick up all stragglers and convalescents and send them there.[ii]

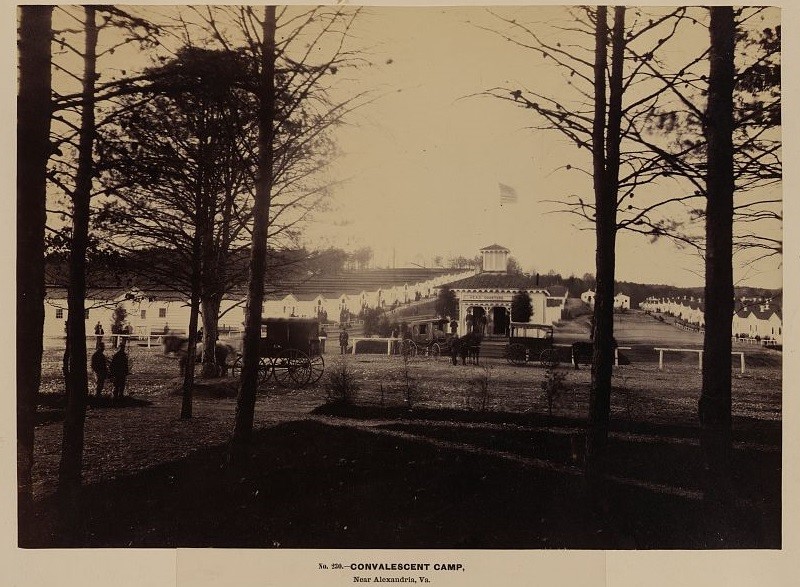

The immediate response produced a camp at the eastern base of Shuter’s Hill, where officers on temporary assignment hastily threw together tents to house a motley crowd of deserters, walking wounded, men returning from furlough, and recruits, all generally demoralized. Under guard by a small contingent of some of the estimated ten to fifteen thousand inmates, in floorless, unheated tents on low damp ground, the camp soon attracted considerable attention, none of it favorable. “Camp Misery” the men called it and, as winter loomed, “a perfect Golgotha.”[iii]

A private organization, the United States Sanitary Commission, stepped in and employees such as Dorothea Dix and Amy Bradley worked virtual miracles in providing food and clothing to the distressed soldiers. The army itself soon mustered the energy and leadership to straighten out the situation, adopting several approaches to the mix of challenges presented by soldiers variously able or willing to return to their units. Medical boards were set up to inspect the men and either discharge them, return them to hospital, or send them on to their regiments. And Provost Marshal General Patrick, on the orders of army commander McClellan, sent a deputy to Alexandria to streamline and personally oversee new procedures for returning able bodied men to their commands.[iv]

The greatest change came in early December 1862 when the army moved the camp to Arlington. The new location lay on higher ground behind Fort Barnard and north of Four Mile Run, with a short spur off the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad (later the Washington and Old Dominion) leading to a station roughly in the neighborhood of today’s Drew Elementary School. General Heintzelman ordered all the spare firewood available in the Defenses directed to the site, as well as new tents and lumber for both tent flooring and the construction of barracks.[v]

By January 14, 1863, Inspector General Lathrop would report, “The troops are now comfortable. All the convalescents are either in barracks or in tents, with stoves and floors.” The time for medical examination and discharge had been reduced to a week and could be reduced further, clothing was plentiful, barracks for 5,000 men would be completed in ten days, and with greater effort up to a third of the 8,108 men in camp could be immediately returned to duty.[vi]

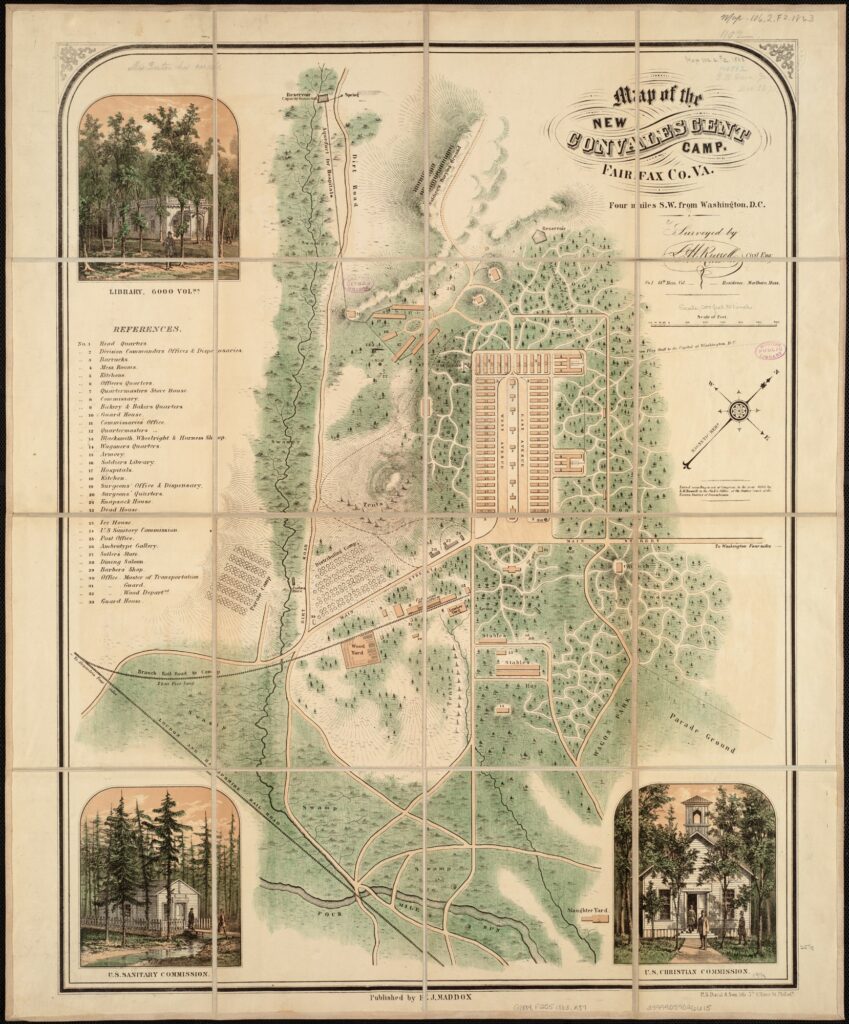

In the following months construction of permanent buildings by the camp’s soldiers continued. A map of “The New Convalescent Camp” prepared in 1863 shows extensive barracks, wards, kitchens, and other structures, and includes illustrations of attractive buildings for the Sanitary Commission, Christian Commission, and camp library. Speculation that this represents more of a plan than an actuality is countered by contemporary photographs as well as reports in The Soldier’s Journal, a newspaper published in the camp itself, starting in January 1864.

According to the reporter, by then the camp held new barracks and mess halls for five thousand convalescents and Sibley tents for a thousand recruits and men returning to their regiments; the tents comprised a “Camp Distribution” adjacent to “Camp Convalescent.” There were also hospital wards for five hundred patients, a bakery capable of producing sixteen thousand loaves of bread a day, two reservoirs that piped in fresh water for the hospitals and kitchens, a post office, an Adams Express office, barber shop, “Photograph Gallery,” a library, and a chapel.[vii]

In May 1863 came an additional change when the War Department established the Invalid Corps — a new formation for men disabled for active field service yet still capable of performing guard and provost duties. This gave a large number of convalescents the opportunity to continue in service with full pay and rations while performing lighter, presumably safer duties and relieving more active soldiers for “the front.” The first troops raised for this national force were a company from the camp in Arlington.[viii]

Unfortunately, the name chosen for the organization produced the acronym “I.C.,” which in the army already stood for “Inspected/Condemned” supplies and equipment, leading many to refer to the Invalids as “Condemned Yanks.” Within a year the organization was given the more impressive designation of “Veteran Reserve Corps,” but the joke remained.[ix]

The camp’s Consolidated Report for September 1862 through December 1863 provides impressive statistics on the scale of operations there. During that period the camp received 117,000 convalescents, sent more than 98,000 on to their regiments, and transferred a further four thousand to the Invalid Corps. Another 31,000 soldiers passed through Camp Distribution leaving fewer than two thousand remaining at year’s end. During this same time about 15,000 men were discharged or returned to general hospitals. Only 260 died.

The proportion of convalescents to troops awaiting transportation back to their units had so decreased that at the beginning of 1864 the camp was officially renamed the “Rendezvous of Distribution.” By the end of June 1864, the return for the Department of Washington showed 1,600 officers and men in the camp “present for duty.”[x] Two weeks later all of them would be needed.

In July, rebel general Jubal Early, commanding his corps of the Army of Northern Virginia and rebel forces in the Army of the Valley, would descend on a capital whose long-time garrison had been stripped to provide reinforcements for Grant’s army besieging Petersburg and Richmond. The troops remaining in Washington were not the ideal force for defending such a vital target, consisting of newly raised artillery companies, Ohio national guardsmen, and miscellaneous small commands.

Arguably among the most seasoned of the capital’s defenders were the dozen small battalions of the Veteran Reserve Corps then stationed in the defenses north and south of the Potomac.[xi] While the War Department quickly summoned reinforcements from Grant’s army, it would take time for them to arrive. In the emergency every man capable of bearing arms was summoned into service, including walking wounded from the hospitals, government employees, and the entire force of the Rendezvous.

Alfred Bellard, a veteran of the Third Corps serving in the 12th regiment of Veteran Reserves on the skirmish line near Fort Stevens, recorded that on the morning of July 11th, “Re-enforcements now commenced to arrive, about 3,000 from camp distribution, both white and black.”[xii] In fact they numbered not quite 2,000, but his statement supports other evidence that Arlington’s contribution to the defense of the nation’s capital included not only the men from the Rendezvous but United States Colored Troops from nearby Camp Casey, news from which also appeared from time to time in The Soldier’s Journal.

Few of these soldiers came under hostile fire, but their presence in the defenses proved decisive in causing Early to delay his assault until reinforcements arrived from Grant’s army to drive him away. As a soldier of the Quartermaster Department noted, the presence of even untrained men on the lines reminded the rebels that “we were at home and prepared to receive company.”[xiii]

As the dust of the departing rebels and their pursuers wafted away from the Northern Defenses a new problem presented itself at the Rendezvous. Once all the able-bodied men or walking wounded had been marched out from all the general hospitals of the District and Alexandria the War Department discovered just how many convalescing or fully recovered soldiers had kept themselves away from the front, the VRC, and the Rendezvous. Just a week after the firing ceased at Fort Stevens the Journal would report, “At no time since the camp was changed from a convalescent depot to Rendezvous of Distribution, has it been so completely jammed as at present.”[xiv]

It would take a few weeks, but the systems of examination, organization, and transportation already established would soon restore the relative quiet of the camp, and the requirement for it would gradually decrease. In February 1865 the War Department discontinued the Rendezvous, transferring its functions to the Soldiers Rest in Alexandria. The buildings were turned over to the Medical Director for the use of staff and patients in Alexandria’s hospitals, which were to be returned to their owners.[xv]

The penultimate issue of The Soldier’s Journal came out on February 1, and the final issue in June was datelined Augur General Hospital. The hospital continued to be listed in directories till late September.[xvi] Not long after it would have shared the inglorious fate of nearly all the vast number of other army facilities built here during the war. On the auctioneer’s block, site by site and building by building, they were sold off for the price of secondhand lumber. But who knows — some of that lumber may still remain, in the beams and rafters of Arlington’s oldest remaining homes…

About the Author

M. A. Schaffner is an amateur historian who lives with spouse and pugs in a house built cheaply 110 years ago in Arlington, Virginia. Schaffner has given presentations on several topics to a number of Civil War Round Tables as well as at the Museum of Civil War Medicine. A reenactor in several Civil War units, including Company B, 54th Massachusetts, they also serve as a member of the Arlington Historical Society’s Board of Directors.

In addition to history, Schaffner’s interests include poetry, with works recently published or forthcoming in The MacGuffin, Illuminations, The Writing Disorder, Sybil, and Beltway. When not avoiding home repairs through Civil War miscellania and poetry, M. A. wades through the archival records of the Second United States Colored Infantry (1863-66) with a view toward compiling a regimental history.

Sources

[i] War of the Rebellion [WOR] Series I, Vol. 19, part 1, p. 504

[ii] Ibid. part 2, pp. 265 & 309

[iii] Livermore, Mary A. My Story of the War, Hartford 1889, pp. 251-256

[iv] WOR, Series I, Vol. 19, part 2, pp. 302-303, 365, 508-509

[v] The Soldiers’ Journal, February 17, 1864, pp. 1-3

[vi] WOR, Series I, Vol. 21, pp. 970-971, 1004

[vii] The Soldiers’ Journal, February 24, 1864, pp. 1-2

[viii] WOR, Series III, Vol. 3, pp. 225-227

[ix] Bellard, Alfred, Gone For A Soldier, Boston 1975, pp. 236-238

[x] WOR, Series I, Vol. 37, part 2, p. 697: total present for duty at Rendezvous, 1,612; at Camp Casey (“Provisional Brigades”), 270

[xi] Benjamin Franklin Cooling, Jubal Early’s Raid on Washington, University of Alabama Press, 1989, pp. 259-261

[xii] Bellard, p. 271

[xiii] Cooling, p.117

[xiv] The Soldiers’ Journal, July 20, 1864, p. 5 [numbered 180 of the year]

[xv] The Alexandria Gazette, February 13, 1865, p. 3 and The Evening Star of the same date, p. 2

[xvi] Daily National Republican, September 27, 1865, p. 1