Table of Contents

Museum members are the reason we can bring you scholarship like this.

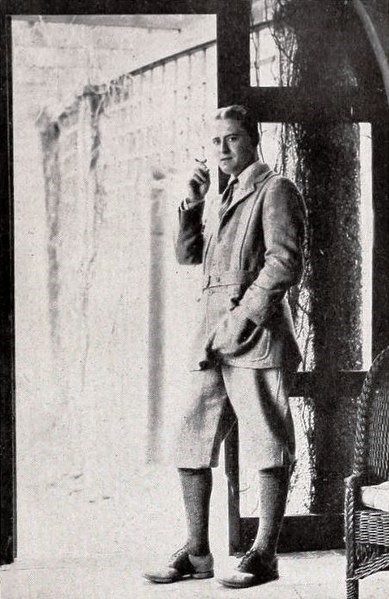

F. Scott Fitzgerald is most commonly known for his novel The Great Gatsby and extravagant parties of the “Roaring 20s.” What you may not know is nearly all of Fitzgerald’s writing is connected in some way to his lifelong fascination with the Civil War. Fitzgerald’s father, Edward, was a young boy in Maryland during the Civil War where he alleged to have rowed a Confederate spy across a tributary of the Potomac River during Jubal Early’s 1864 invasion of Maryland and inspired his son’s passion for the Civil War and the South by telling him stories.[1] Creatively and personally exhausted in the 1930s, Fitzgerald changed the way he wrote, beginning to use Civil War settings and references to make major plot points.[2] Two story drafts, recently published for the first time, titled “Thumbs Up” and “Dentist Appointment” use Civil War dentistry as a backdrop to explore Fitzgerald’s favored theme of how a confident woman can impact an ambitious young man.[3] Though entirely fictional, these stories raise questions about Civil War dentistry and the men who practiced the emerging specialty.

The plot of both stories centers on the flirtation of Josie Pilgrim and Tib Dulaney, a Confederate cavalrymen and postwar newspapermen. But for Civil War buffs, the star of the story is Captain Dr. Pilgrim, a Union surgeon home recuperating from a wound received at Cold Harbor. Dr. Pilgrim and his sister find themselves caught up in the Confederate retreat away from Washington, D.C. from the 1864 battle of Fort Stevens, described by Fitzgerald as “throwing a few shells in the suburbs.”[4] Informing his Confederate captors that he was a physician, specifically, a dentist, Pilgrim was whisked away to extract a tooth from a French observer attached to Jubal Early’s staff. The cavalrymen’s surprise at finding a dentist is understandable, given that the first American dentistry school had only been established in Baltimore in 1847, with schools in New York and Philadelphia also opening up before the war.

At the time of the Civil War, dentistry was establishing itself as a legitimate medical specialization. A group of scholars rightfully identifies the Civil War as the pivotal moment in the development of dentistry.[5] Dental schools had produced 400 graduates before the war, accounting for a small portion of the 5,500 dentists listed in City medical directories in 1860.[6] The French observer, a cousin of Napoleon III, expresses hesitation about the dentist about to extract his tooth – feelings perhaps not uncommon to modern readers. When the Frenchman exclaims “cette vie barbare” {trans: this barbaric life}, Dr. Pilgrim stiffly responds, “I am a trained surgeon.” Pilgrim’s stiff response exemplifies how dentists were fighting for professional legitimacy during the Civil War. Unlike other doctors of the time, medically trained dentists realized that dental ailments were almost exclusively local issues that required local treatment, traditionally the extraction of a tooth.[7]

Fitzgerald’s decision to have a Union dentist treat a Confederate patient is an ironic one because the Confederacy took dental health more seriously than the Union. As Secretary of War in the Pierce administration, Confederate President Jefferson Davis had advocated for the creation of an Army Dental Corps, though his plan was rejected.[8] During the war, Confederate Surgeon General Samuel Moore saw value in attaching dentists to Confederate armies so that men could receive proper care and return to their units quicker. The 1864 Conscription Act specifically targeted dentists not already in the service of the army and attached them to military hospitals where they could perform “twenty to thirty fillings…the extraction of fifteen or twenty teeth, and the removal of tartar” in a single day. One Confederate dentist described his operating space “A room with a good light, cold and warm water, soap and towels, and a servant or soldier, were invariably provided. The making of the operating chair was entrusted to the hospital carpenter, and generally constructed by a rude design drawn in pencil. A tin basin placed upon a bench or stool answered for a spittoon.”[9] Certainly a luxurious space when compared to some operating conditions during the war. As a contrast to the Confederacy, the Federal government saw little use in assigning dentists to its army, leaving soldiers to either receive treatment from general physicians, or seek out civilian dentists for their ailments.[10]

In Fitzgerald’s story, dentistry also demonstrates the limits of reconciliation between former Confederate and Union foes. In one section of the story that takes place after the war, Southerner Tib Dulany admits “I am not an American. I am a Virginian. Those two things will never mean the same again in my lifetime.”[11]

Civil War physicians were not apolitical practitioners of their craft. Rather, they were intensely political participants throughout the Civil War. In 1868 his article “Dental Notes on the Civil War”, Dr. Watkins Leigh Burton, a Confederate Dentist during the war, articulates some of the foundational tenants of the Lost Cause while defending Confederate medical practices during the Civil War. Burton attempts to vindicate the Confederacy stating in his conclusion: “with the ports of the world closed against them, with a currency depreciating every hour from the most shameful mismanagement ; and having to contend against such enormous odds, the great wonder is, how even a noble and heroic people, believing honestly in the justness of their cause, could hold out so long.”[12] Burton characterizes Southern physicians as wise men who did more with less, who only failed because of Northern blockades and material shortages – key elements of the Lost Cause.[13]

Though a work of fiction, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s stories are grounded in the real experiences of Civil War dentists. The specialization of dentistry was just coming into its own during the Civil War and its professionalization was fleshed out by the advances that war time experimentation allowed. As a group of scholars and physicians note “1860s dentists rose to the challenges by experimenting with materials and techniques beyond those described in the literature of the day.”[14] The war presented the opportunity for dentists to demonstrate the legitimacy of their field and they did not miss their opportunity. More than just practitioners of a craft, Fitzgerald’s stories provide a fictionalized depiction of the very real political sentiments held by Northern and Southern physicians.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Cameron Sauers is a student at Gettysburg College, where he is a History major with minors in Public History and Civil War Era studies. Cameron is a Fellow at the Civil War Institute and is currently Co-Editor in Chief of the Gettysburg College Journal of the Civil War Era. Cameron can be reached on twitter @cam_sauers

Endnotes

[1] James R Mellow. Invented Lives: F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.(Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984), 20. John Irwin F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Fiction: An Almost Theatrical Innocence. (Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.), 12.

[2] Cameron Sauers “Borne Back Ceaselessly into the Past: Fitzgerald’s Forgotten Civil War Literature” The Gettysburg Compiler

[3] Justin Mellette, “Of Empress and Indians : A Compositional history of ‘The End of Hate” The F.Scott Fitzgerald Review, vol. 12 no. 1 (2014), 122.

[4] F. Scott Fitzgerald “Thumbs Up” in I’d Die for You and Other Lost Stories. Edited by Anne Margaret Daniel. (New York, Scribner, 2017), 165.

[5] Richard A. Glenner, P. Willey, Paul S. Sledzik, Erich P. Junger, “Dental Fillings in Civil War Skills: What Do they Tell Us” in Journal of the American Dental Association. Vol. 127 (November 1996) 1671.

[6]Glenna R. Schroeder- Lein “Dentistry” in Civil War Medical Encyclopedia.(New York: Routledge, 2008),84.

[7] Laszlo Schwartz “The Historical Relations of American Dentistry and Medicine.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 28, no. 6 (1954): 544 www.jstor.org/stable/44443907.

[8] Civil War Medical Encyclopedia, 84.

[9] Watkins Leigh Burton. “Dental notes on the late Civil War”. American Journal of Dental Science. 1868;3:444.

[10] Douglas Richmond “No Teeth, No Man: Dentistry During the Civil War” Civil War RX Blog https://civilwarrx.blogspot.com/2014/08/no-teeth-no-man-dentistry-during-civil.html

[11] F. Scott Fitzgerald, “Thumbs Up”, 182.

[12] Burton, 448.

[13] Allan T. Nolan “The Anatomy of a Myth” in The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History. edited by Gary Gallagher and Allan T. Nolan. (Bloomington, IN. Indiana University Press, 2000), 26-27

[14] Dental Fillings, 1676.